Agnes Strickland's Queens of England (42 page)

Read Agnes Strickland's Queens of England Online

Authors: 1796-1874 Agnes Strickland,1794-1875 Elizabeth Strickland,Rosalie Kaufman

Tags: #Queens -- Great Britain

and presided over a grand banquet in the evening. His sys tern was very much run down by the strain of hard study, and this day of excitement proved too much for him. The following morning found him with a sick headache and sore throat, and towards night he became deUrious. The family physician reduced the little duke's vitality still further by bleeding him according to the custom of the times. He grew worse, and there was great lamentation m the royal household because the princess's quarrel with Dr. Radclifife prevented his being summoned, for everybody had confidence in his skill. At last a messenger was dispatched with a humble request to the doctor to visit the little sufferer. After a great deal of urging he consented, and pronounced the disease scarlet fever. He asked who bled the duke. The physician in attendance replied that he had done so. " Then you have destroyed him, and you may finish him," said Radcliffe, " for I will not prescribe."

Of course the learned man was much censured for wilfully refusing to save the child, but he knew only too well that all his efforts would have been of no avail. Five days after his birthday festival the little duke expired.

Lord Marlborough, who had gone to Althorpe, was summoned to the sick bed of his youthful master, but arrived too late.

The bereaved mother watched beside her dying boy to the end, hoping against hope ,• and when nothing remained but his lifeless body, she arose, and with an expression of sad resignation on her countenance, quietly left the room. Then her thoughts were directed towards the father she had wronged, and she wrote him a letter filled with the most penitent expressions, and telling him that she looked upon her cruel loss as a blow from Heaven in punishment of her cruelty towards him. Retribution had come at last!

At that moment, when the object in whom all her hopes were centered lay cold in death, Princess Anne yearned for the sympathy of the parent who had ever been most kind and indulgent to her, and she immediately sent her letter to St. Germain by express.

Lord Marlborough forwarded the sad news to King William, but his majesty made no reply for three whole months. The reason for this neglect was because Anne had written to her father, and the king found it out, although it was managed, as she thought, very secretly. William had always shown so much affection for his nephew that his failing to send any message of condolence or sorrow was the more remarkable.

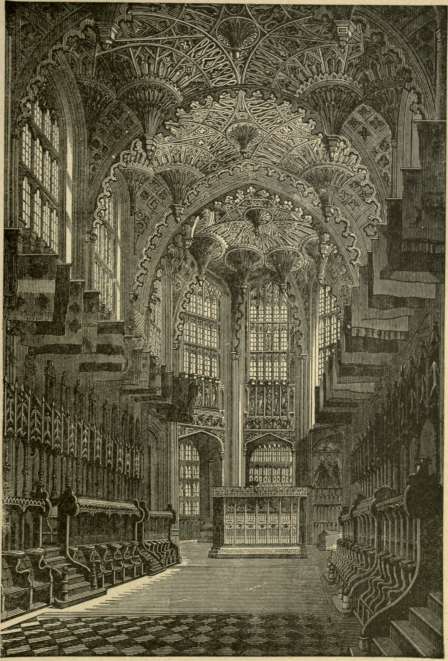

The little duke's remains lay in state in the suite of apartments he had occupied, and afterwards they were removed to Westminster, to be interred in Henry VII.'s Chapel. The English ambassador at the court of France was placed in a very embarrassing position, because his sovereign did not order him how to proceed with regard to the Duke of Gloucester's death. The fact is William was in a fit of temper, possibly caused by the sad event, and so cared not how he perplexed others. Besides, although he had loved the dead boy, he despised the parents, and paid no more respect to their feelings than if they had lost a favorite dog. At last, after the expiration of two months, he ordered a fortnight's mourning, which was very little. Three months after the death of the little duke. King William condescended to write, not to the afflicted parents, but to Lord Marlborough, and this is a copy of the remarkable missive: —

" I do not think it necessary to employ many words in expressing my surprise and grief at the death of the Duke of Gloucester. It is so great a loss to mj, as well as to all England, that it pierces my heart with affliction."

CHAPEL OF HENRY VII,

The same post carried a peremptory order that all the salaries of the duke's servants should be cut off from the day of his death.

[A.D. 1701.] Thus we see that the king's heart was not so pierced with affliction as to prevent his having an eye to economy. It was even suspected that it was the approach of pay-day that prompted him to write at all; but the Princess Anne was so shocked at the king's meanness that she resolved to pay the salaries of her dead boy's servants out of her own purse rather than send them off at a moment's notice. She returned to St. James's Palace towards the end of the year, bowed down with desolation and sorrow.

The death of the Duke of Gloucester was not much lamented in the political world, for his existence had been rather an obstacle to the designs of the various parties; but to his mother, aside from her deep sorrow, it proved an event of the utmost importance ; for even in her own household her position was altered, and she was not treated with the same deference as before.

Lady Marlborough was the first person by whom the change was made apparent, though she of all others had most reason to be grateful to Princess Anne. She had gone with her husband to Althorpe, just a short time before the little duke's death, to further a scheme that they had made between them. King William's health was so poor that they had reason to believe it would not be long before Anne would replace him on the throne. When that should occur, it was argued that she would be assisted in the government by certain statesmen, who would shrink from any cooperation with them, so they planned a strong family alliance that would greatly strengthen their influence. They were aided by the sly politician, Sunderland, and by Lord Go-dolphin, whose only son had, during the previous year,

married their eldest daughter. When this marriage took place Princess Anne presented the bride with five thousand pounds, and gave a similar sum to Lady Marlborough's younger daughter, Anne Churchill, when she married Sunderland's son.

These two marriages formed the principal features in the Marlborough scheme for their own advancement when the proper time should come. For the purpose of doing away with formality when writing to her favorite, it had been early agreed that the princess should merely be addressed as Mrs. Morley, and Lady Marlborough as Mrs. Freeman, which brought them to the same level. Since her bereavement Princess Anne had become more humble, and Lady Marlborough more imperious. When the latter was absent she received three or four notes a day, some of which were signed "your poor, unfortunate, faithful Morley." But the indulgence and kindness of the princess had only spoiled the woman, who was so puffed up by prosperity as to render herself positively ridiculous. She even went so far as to avert her face and turn up her nose when she had any slight office to perform for her benefactress, as though there was something about her person that produced disgust. In course of time the princess began to notice what others had seen for a long while; but accident revealed to her one day the extent to which the ungrateful creature could go with her insults.

One afternoon when Princess Anne was at her toilet, she requested Abigail Hill to fetch her a pair of gloves from the table in the adjoining room. Miss Hill passed into the room designated, leaving the door open behind her. There sat Lady Marlborough reading a letter. Miss Hill soon discovered that she had, by mistake, put on her royal highness' gloves, and gently called her attention to the fact. " My goodness ! " exclaimed Lady Marlborough,

" have I on anything that has touched the odious hands of that disagreeable woman ? Take them away quickly," and she pulled off the gloves, which she threw violently to the ground. Miss Hill picked them up without a word, and left the room closing the door behind her. Lady Marlborough thus remained in ignorance that her disgraceful speech had been overheard ; but Abigail Hill saw plainly that not a word of it had been lost on the princess, who never forgot or forgave the disgust manifested by the woman on whom she had lavished affection and favors. Fortunately, the princess had no other attendant besides the one she had despatched for the gloves, so the incident remained a secret for the time being. Lady Marlborough was made to feel on several occasions that she had seriously offended the princess, but was at a loss to know how or when. She could not reaily have felt the disgust she expressed, because Princess Anne was renowned all over Europe for the beauty and delicacy of her hands and arms; but perhaps it was envy.

Princess Anne had not taken off mourning for her son when news arrived of the death of her father. This event did not cause her a great deal of sorrow, nor did she think fit to take the slightest notice of the request he made in his farewell letter to her, that when William should die she would make way for her brother on the throne.

King William was at Loo, in Holland, when James H.'s message of forgiveness was delivered to him, and he was so impressed by it that he sat in moody silence the entire day. That was his way of showing that he was painfully affected ; but it did not remove the ill-feeling he felt towards the dead king for refusing to permit him to adopt his son, — a request he had made after the death of the Duke of Gloucester. Neither did it prevent his issuing a

bill accusing the young Prince of Wales, a boy of twelve, of high treason. But he put on mourning for his uncle, and ordered his footmen and coaches to appear in black. All the nobles and the court of England imitated him, and mourning became the fashion.

His majesty returned to England, as usual, in the autumn, and left the Earl of Marlborough in command of his military forces in Holland, feeling certain, as he said, that the talents of that general would enable him to continue in his stead should his death occur. And it did not seem far off, for William had been seriously ill, the effects of which had so reduced his already enfeebled frame that all who saw him knew he was not long for this world. Nevertheless, he busied himself with preparations for involving England in a war with France, the object being to divide Spain into three parts, to be claimed by Austria, Holland, and England. This was to prevent Louis XIV. from becoming too powerful by his influence over his grandson, who was heir to the Spanish throne.

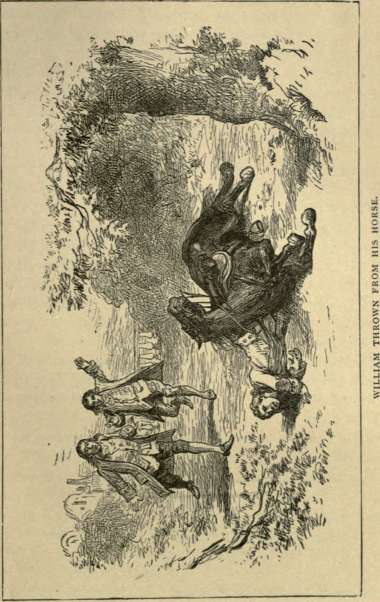

It was no other than John Fenwick's sorrel pony that brought William's warlike projects to a close. And this is how he did it: His majesty was fond of the pretty animal, and rode on him daily while superintending the excavation of a canal in Hampden Court grounds. It was on the twenty-first of January that he was riding about as usual, when suddenly the pony stuck one foot in a mole hill and fell, throwing his majesty over on his right shoulder, and breaking his collar bone. Some workmen assisted him to rise, and carried him to the palace, where the broken bone was soon set. The accident might not have proved serious had not William, with his usual obstinacy, insisted on driving to Kensington that night. The jolting of the carriage displaced the fractured bone, and he arrived in a state of exhaustion and suffering. The opera-

tion had to be repeated, but it was several da}'s before the patient could move. Even then his mind was filled with revenge, for he sent a message to parliament urging them to lose no time in passing the charge of high treason against little James Stuart, that had been under consideration since the preceding January. The very last act of this mighty monarch was the signing of this bill, to which he affixed his stamp a few hours before his death.

On the first of March the royal sufferer was seized with cramps, but improved sufficiently to be able to walk in the gallery of Kensington Palace a few days later. Feeling fatigued from the exercise, he threw himself on a lounge and fell asleep in front of an open window. Two hours later he awoke with a chill, the precursor of death. Both the Prince and Princess of Denmark made repeated efforts to see the dying king, but to the very end he framed his lips into an emphatic " no!" every time the request was made. No one was admitted to the sick-room besides physicians and nurses, excepting the old favorites Bentinck, and Keppel, Earl of Albemarle. The latter arrived from a mission to Holland just before the king lost his speech, and gave his royal master information of the progress of his preparations for the commencement of war in the Low Countries. For the first time the dying warrior listened to such details with cold indifference, and at their close merely said: " I draw towards my end," Then handing Keppel the keys of his writing-desk, he bade that favorite take possession of the twenty thousand guineas it contained, and directed him to destroy all the letters enclosed in a certain cabinet.