Airmail (12 page)

Authors: Robert Bly

Have Myrdal’s articles appeared anywhere in the American press? What he writes is purely self-evident, but since he seems to have a—perhaps undeserved—reputation in the U.S., maybe they could do some good.

Warmest greetings

Tomas

7 Sept, ’67

Dear Tomas,

Forgive my slowness! I get slow and lethargic in August, like the sap in trees, and besides, I’ve been sick! (Read Alan Watts—his

Nature, Man and Woman

is a wonderful book—if it’s not in Swedish, let me know, and I’ll send you a copy in English.)

Your translation of “Three Presidents” is wonderful, and I haven’t a single criticism. If you are doubtful about “resilient”—I could say this—the line suggests that the air is mentally very quick. It can choose from many alternatives, and is flexible, and able to think fast. If a rock comes up in its path, it just doesn’t run head-on into it, like a bull or Lyndon Johnson, but it may sidestep it, go around it swiftly.

Thank you for the Myrdal articles and the new poems! I love that blue lamp. Two nights ago a friend, a potter who knows Swedish, came by heading for San Francisco and we spent the whole evening huddled happily over your

I det fria.

I like the poems immensely, and am determined to translate it. So I have some questions for you, Dad.

Is the bulpong tarning a cube (as they are in the U.S.) or just a

rectangle

?By

stark

do you wish to suggest “uncompromising”?In “De myllrar i solgasset” do you want the English reader to see the

crawling action

of ants (or insects) or their

busyness

?The man who “sitter pa faltet oah rotar”—is he sitting down? on a chair? What is he doing? Raking? Or digging with a stick?

The “ogonblicksbild”—that word isn’t in my dictionary! Does it refer to the shutter action of a fast camera? Does it refer to the shutter action of a fast camera?

Does the letter put the

speaker

in the position for a while of the

man digging

on whom the shadow of the cross falls? The image of the cross in the airfield is a

wonderful

image, but something very ominous clings to it.

Write soon!

Your old friend

Västerås 9-30-67

Dear Robert,

it was good to get your letter, thanks! I had an uneasy feeling that something had happened to you, that you were sick or something of the sort. (I don’t have such a romantically dreadful idea of the U.S. that I believed you’d been arrested!)

[------]

In other news, we’ve acquired a pet, a guinea pig named Tyra. Our guinea pig became very good friends with the English poet Jon Silkin, who was here fourteen days ago—he was in the process of putting together a Sweden issue of

Stand.

(He was very satisfied with your translations of me.) After a day or so I drove him to Uppsala and left him with the co-editor of BLM. First we visited a fairly notable novelist that Silkin wanted to include. The novelist just sat like a depressive Buddha, mumbling that he hadn’t written anything worth reading. In other words he had been smitten with political sickness. Swedish literary life is filled primarily with people who beat their breasts, damn literature, and promise to mend their ways. Many sleep with

Mao’s Little Red Book

on their bedside tables. I speak of the cultural scene of course; society is otherwise becoming increasingly bourgeois and we will have a conservative victory next fall. I feel in great need of that book by Alan Watts, Robert! It’s not to be found in Sweden. (However there’s another one, on Zen Buddhism, checked out of the library.) My contact with the universe nowadays consists primarily in walking around in the woods hunting mushrooms (MUSHROOM-POWER!), woods that unfortunately aren’t so far out that you can’t hear the breathing of industry. But there are mushrooms everywhere, even a few yards from the cathedral and library in the middle of the city. They say there are some unusually big fat mushrooms in the churchyard...

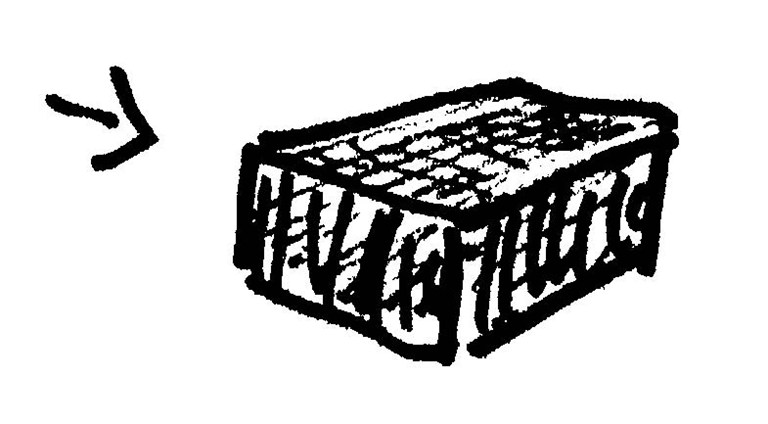

And now your questions about old “In the Open.” Bouillon cubes in Sweden are usually shaped like this:

in other words not cubes exactly but four-edged in any event. (“Rektangel” evokes surface, not volume.) Birgitta Steene, who made a first version of the poem, translated it “auburn box.” STARK just generally means strong; here the closest word would be

concentrated.

She translated “Myllrar i solgasset” as “teem in the blazing sun,” as I recall—I haven’t got the translation here. The word myllra in Swedish gives a rather strong feeling of urgent crowding, however, something rather physical and also with certain associations of anthills (as you will recall, we have large anthills in this country). And then the man who sits ROOTING AROUND. Root [rotar] is a rather weak word, it means that he pokes, touches, or digs in the soil, but you can’t really see what he’s doing—the distance is great. I don’t remember if I was conscious of this then, but after the poem was written I couldn’t help associating it with the Vietnamese peasants. Halberstam describes in his

Making of a Quagmire

how he flies at a low altitude over the landscape and how some farmer pretends not to notice the plane, because the Vietnamese peasants have now learned that if they leap up and run for cover they’ll be shot, as they will then be considered to be “Viet Cong.” As it happens I read Halberstam after writing those lines; it gave me a sort of déjà vu experience. But that last part of the poem is in no way invented, it is SEEN, it is

The Lion’s Tail and Eyes.

If the airplane cross in the first lines is something dangerous, threatening, negative, I understand the cross in the concluding lines as something positive, helpful, but at the same time violently elusive-recursive, something nearer to us than anything and also something we can only glimpse for an instant, not hang on to. Commenting on all this gets to be rather rhetorical and feeble, it must be seen, and you can probably see better than anyone else.

Write soon! (I will write soon myself.)

Best wishes, happiness and prosperity!

Your friend Tomas T

2 Oct, 67

Dear Tomas,

Here I am sitting, proofs of a little Ekelöf selection in front of me, about to make a ghastly mistake that will make me the laughing stock of the American Scandinavian Foundation forever! Help me!

In

Strountes,

Ekelöf has a poem about the dead slipping out of the cemeteries at night. The word “knäsatt” is what I don’t understand. What does it mean?

The first six lines go this way:

När de slipper ut genom körgardsgrinden

en pasknatt, en pasknatt

När de döda gar ut och betitta staden

en manskensnatt, en man-natt

Da är det evig hemlöshet some gör sig knäsatt

knäsatt hos andra döda

Now Christina told me the odd word “knäsatt” meant

sitting on the knees of

. So the last two lines above are now translated:

Then it is the eternal homelessness that is sitting on the knees

the knees of the other dead

But it doesn’t really make sense! Is that what it means? My dictionary seems to say the word means something like “legalize,” as if one would say, “We’re going to get this common law marriage legalized.”

But if that is so, then the eternal homelessness seems to be legalizing

itself

.

Could it be:

Then the eternal homelessness is taking its rightful place

taking its place with all the dead

Or

Then the eternal homelessness takes its rightful place

Takes its place in all the dead

Did the Harper book, my new one, come yet?

Please answer very soon—I’ll have to commit hari-kari if I make such an idiotic mistake and get the knees in these tangled up...

Thank you!

Robert

Västerås 10-7-67

Dear Robert

you’re getting two letters at once. While I was in the middle of writing the other letter (which is in this envelope), your much-longed-for book arrived, and then two days later this SOS about KNÄSATT. I’ve been reading the book on a recent train trip through southern Sweden (I’ve been lecturing on the testing of criminals), reading and heating my imagination—it is—OH—it is fantastically good...but first

KNÄSATT

[knee + set]

a word which is very seldom encountered, a word with a curious, half-bureaucratic, half-aristocratic atmosphere. It is met with most often in parliamentary debates of the more solemn sort, in phrases like “we of the committee have not chosen to knäsatta the principle concerning taxation of...” etc. It means ACCEPT, more or less. MAKE YOUR OWN. LEGALIZE. Originally it must have meant ADOPT—that is, you took a child and sat him on your lap, and that meant you made the child your own. But nowadays the word appears only in its abstract, symbolic meaning. And that, as I said, is rare. The very fact that it appears so seldom, and that KNEE in and of itself is so concrete a thing, makes the effect rather curious. The knee constantly presses through the abstract meaning. This is particularly true in the context in which Ekelöf uses the word. It floats constantly between the bureaucratic-abstract “knäsatt” and the extremely macabre and tangible knees of the dead (skeleton knees?). Besides that, it’s a half-rhyme with “moonlit night” [månnatt]. In Swedish the effect is that of a strange kind of qualified nonsense. This poem can’t be translated. It plays constantly on nuances within the language, that is, the Swedish language. As I fancy the poems of Lewis Carroll can’t be translated. Would you be able to do something with Legalize and Legs? “Taking its rightful place” is of course not wrong in its way, but it would be like arranging a Chopin scherzo for a military band. I hope I haven’t discouraged you? Go on Bob, go on.

It was wonderful to be able to sit reading your book while I rolled forward through a rainy Sweden. I had longed to have it for so long, and imagined that some damn businessman at Harper’s had moved the publication date back six months or so in order to rush Svetlana’s memoirs through, or something else that would sell. But here it came after all. What surprises me a little is that it turned out to be so strong as a whole, that in fact it is a book, with a rich, composite but still integrated spirit. Many little eddies that yet are part of the big whirlpool. Even poems that individually have struck me as strange (for example “Watching Television”) have a strong meaning in their context here. And the poems do not die after many readings, they are resurrected during the night and are just as remarkable when one returns to them. Later on I hope to be able to send you some words of criticism as well, but here at the beginning I only want to trumpet forth my mole-like gratitude.

You must write very soon and report how it has been received. Not that it makes much difference as far as the poems are concerned, but it’s interesting to me to see how literary life of the U.S.A. operates. A man who ought to have certain difficulties (or maybe it’s all too easy for him) in writing his criticism is James Dickey. I was quite shaken by your dispute in

The Sixties,

it was as if the unhappy fellow was being hurled from the Tarpeian Rock by some majestic lictor clad in a suit of armor made of flowers but with a stern, set face. I’ve never managed to read

Buckdancer’s Choice

myself. The poems are so swollen, so many words...It’s like being a child and sitting with a gigantic serving of porridge in front of you. Besides which I lost interest in Dickey, a bit, after the interview in

Life.

Anyway I’m thinking of finishing that poem about Pappa in the hospital window. That’s the end of letter no. 2. Now read letter no. 1.

12-18-67

Dear Robert,

it’s hard to write, since my youngest daughter wants to be here too—she’s spreading herself across the whole table. Well, what I want to say is BREAK YOUR SILENCE and tell me what happened to your wonderful book and what you think about the wonderful book I and (I hope) Bonniers will publish...Is “War and Silence” an appropriate title? Has Bonniers written to you? I’ve heard nothing myself about the project other than that Lars G. was able to get at least one of the press’s mighty editors to go along with the idea. Of course I’m living pretty isolated (snow coming from all sides) but in the morning I’m going to Stockholm to meet some colleagues. The fact is that every year a literary grant is given out by the newspaper

Aftonbladet

and everybody who ever got a grant (I got one in 1958) is invited to a big lunch that usually breaks up around ten o’clock at night in thick fog and slurred discussions. You get to meet the new grantee—nobody knows who it is but I suspect that this year it’s going to be Sonnevi, who has published a collection of poems and hasn’t gotten any of this autumn’s grants as yet. So if it’s Sonnevi I’ll have a chance to drag him into a corner to discuss the project—we do need to know whether we’re translating the same poems. And if we are translating the same ones, which version should we use? Etc. I have no idea how frequent your contacts with S. are and what you yourself think of our respective translations. I only met S. once (in Lund) and he seemed to me to be an honest and serious fellow. My picture of his own poetry is very diffuse, owing to the fact that I haven’t read his latest book apart from certain political fragments, which haven’t really convinced me. (But his translations of you are good.)