Alex's Wake (2 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

“It will be on your conscience,” wrote Alex, and Alex was right. In 1945, with the end of the war, the grisly newsreels appeared, documenting the full range of the atrocities that the Nazis had perpetrated, unspeakable crimes that included the murders of my father's family as five among the six million. In addition to Alex and Helmut, dead in Auschwitz, there were Toni and Eva, my grandmother and aunt, deported to Riga, and my father's Grandmother Behrens, murdered in Terezin. The next year, my father gave up his flute and the music profession that he loved in favor of a job selling furniture in a department store, an act of penance for his failure to save his family. In a revealing letter, sent late in his life, my father wrote, “The unanswered question which disturbs me most profoundly and which I shall carry to my own death is whether through an enormous last-minute effort I could have saved my father and brother from their horrible end.”

The guilt that my father carried he passed on to my brother, Peter, and me as our emotional inheritance. The violent fates of their families (my mother, an only child, lost her mother to the camp at Trawniki) were a subject my parents assiduously avoided in my early years. No doubt they wished to protect Peter and me from the truth, for fear that we might have trouble sleeping at night or developing a sense of trust. How little they suspected that, even without words, we could feel and absorb the unspoken pain that circulated like dust in the air of our home, and how much we were aware of the darkness, the enormous unknown yet deeply felt secret that obscured the light of the truth.

My parents' way of dealing with their guilt and sadness was to deny it and keep it hidden. But secrets derive a significant part of their power from silence and shame. “They died in the war,” was my father's curt reply to my brother's direct question about why, unlike all our friends, we couldn't visit our grandparents at Christmas or birthdays. There was nothing more, no stories, no reassurances that their fate would not be ours. And there was no acknowledgment that we were Jews, despite that being the singular reason for our family's violent dismemberment. When I, as a teenager, discovered our religious roots, my father dismissed it all by declaring that we were, at most, “so-called Jews.” He did not choose to regard himself as a Jew, despite the unavoidable fact that he'd been

bar mitzvahed, that his parents were both Jews, and that he and his wife had both performed in an all-Jewish orchestra. “Adolf Hitler thought I was a Jew, so I had no choice. I choose to exercise that choice now. I am not a Jew,” he said.

As I grew to manhood, I became aware of my inherited guilt. In my forties, I began to research the story of my parents' lives in Germany and of their families' lives as well, a tale that I told in

The Inextinguishable Symphony

. But over the years since that book's publication, I have come to see that tale as only the starting point of a journey of self-discovery that I unknowingly began the moment I first asked a question about what happened to my family.

I've come to feel a deep need to connect with that vanished generation, with those members of my family who were murdered a decade before I was born. In one of his letters, my grandfather acknowledged that he was writing on the morning of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. He obviously self-identified as a Jew. So I began to explore Judaism, partly as a purely spiritual quest, but mostly as a way to reach back through those vanished years to try to touch my grandfather. When I heard the Kol Nidre prayer intoned on Yom Kippur, my eyes would fill with tears because of the melancholy beauty of the melody, and also because I knew that, once upon a time, my grandfather had heard that same melody on that same holy night. In the autumn of 2006, I began a twenty-month course of study, discussion, and learning that culminated in my becoming a Son of the Commandment, a Bar Mitzvah Boy, at the age of fifty-five.

With the help of my wife and my therapist, I came to recognize a rhetorical question that hung over me like the mist that follows in the wake of an ocean liner. “How can I ever be truly happy, how can I ever deserve happiness,” I would say to myself, “when my grandfather was murdered in Auschwitz?”

I realized also that, although my grandmothers and aunt had been murdered as well, it was the story of Alex and Helmut that fully galvanized my interest. I became consumed with a desire to know the facts of their voyage on the

St. Louis

and of their three years' imprisonment in France. Eventually it occurred to me why, beyond a certain spectator's

curiosity, that was so. I wanted to learn the facts of their final years on earth because I wanted to save them. My father had failed, and the responsibility had passed to me. I was the backstop, the catcher racing up the first base line to snag an errant throw from an infielder. I couldn't save them, of course. Again, they died ten years before I was born. But my father's burden had become mine and his guilt was mine as well. If I couldn't save them, the least I could do was to place flowers on their graves, to tell the world their story, and to bear witness.

In March 2006, my wife and I visited my father in Tucson, where he and my mother had moved following their retirement, and where George had remained following my mother's death in 1984. George was now ninety-two years old and living alone, and Amy and I thought it was probably time to bring up the subject of assisted living. There is a nice facility nearly across the street from our home in Maryland, and we spent what we thought was a productive Saturday afternoon discussing a possible move east. My father asked several pointed questions but seemed quite interested in the prospect of living so close to Washington, D.C., and all its political and cultural attractions. When we parted that evening, Amy and I breathed sighs of relief, assuming that most of the heavy lifting had been accomplished.

The following morning, when we raised the issue again at breakfast, George became indignant, accusing us of conspiring to take him away from the home he loved. “But yesterday you said that it was such a good idea!” I exclaimed, frustrated by what I took to be the simple querulousness of a cranky old man. We flew back to Maryland that afternoon, unsure what to do.

Within a few weeks our way forward became painfully clear. A neighbor had come to visit George and found him in a heap on the floor, unable to rise. He was taken to a hospital, and several days later a neurologist called me with the news that my father had Alzheimer's disease. What I had taken for a disagreeable refusal to acknowledge a logical plan of action had in reality been my father's simple inability to remember a conversation from one day to the next.

There followed a nightmare of weeks of legal maneuvering attempting to persuade the state of Arizona to declare me George's legal

guardian so that I could move him to Arbor Place, an Alzheimer's facility near us in Maryland. The single worst day of my life came in late June, when we somehow got him on an airplane, doing our best to ignore his repeated vehement declarations that I was behaving like a Nazi and that Amy was a willing Nazi

hausfrau

. His use of those epithets was doubtless evidence of his illness, but no less ironic or painful for all of that.

A slow, sad diminuendo marked the last years of George Goldsmith, during which I had frequent opportunities to visit with Günther Goldschmidt, the young man I'd come to know while working on

The Inextinguishable Symphony

. As I sat with him in the fenced-in garden of Arbor Place at twilight, or, increasingly as time went on, by his bedside in his tiny room, on a slippery brown leather chair we'd brought along from his home in Arizona, he would speak lovingly and longingly of his long-lost homeland. At times, his memories would skip across decades, as when he declared that he first heard the news of President Kennedy's assassination from a passerby on Gartenstrasse, where he'd lived as a child in Oldenburg. Mostly, though, he would share with me his happy memories of playing in the Schlossgarten, the elegant park, formerly the ducal gardens, that began just steps from his father's spacious house. Many were the times that we would plan a return visit to his hometown that I knew would never happen; we'd fly to Amsterdam, I told him, and after a day or two take the train (oh, how he loved trains!) to Osnabrück and then to Oldenburg. He would show me all the sights, we'd hear music in the thirteenth-century Lambertikirche, and we'd stroll together through the Schlossgarten, admiring the rhododendrons and throwing bread crumbs to the ducks who swam contentedly in the park's peaceful ponds. Invariably after these fanciful conversations, my visit would end, he would fall into a happy sleep, and I would drive home in tears.

Then, as a gentle spring took hold in 2009, his decline quickened. In the middle of a rainy April night, a phone call summoned me to a suburban hospital where my father had been rushed when a caretaker at Arbor Place discovered him struggling for breath. A few days later, he was returned to his own little bed under hospice care; his doctor, without explicitly saying the words, prepared me for the end. On Wednesday night, April 29, I had the chance to say goodbye. My father, shrunken

and shaken by his last struggles, could no longer reply as I told him that I loved him and thanked him for my life and for my love of music. He grasped my hand with what must have remained of his strength and opened his eyes wide before closing them and sinking back into his pillow. The next day, shortly after noon, his long journey ended at last.

Exactly eleven months later, on March 30, 2010, I received the shocking, inexplicable news that my brother had died. A once brilliant student at Stanford University who, like me, had gone into the business of introducing classical music on the radio, Peter had in recent years been struck low by physical ailments and a profound depression that, I am sure, was exacerbated by the long-standing family guilt and shame. Now he was gone, quickly felled by a heart attack. He was sixty. The one person of my generation who understood the issues I'd grown up with, intimately and with no need of explanation, had disappeared. My parents, the other two people who'd known me all my life, were also gone. I was suddenly alone, the last Goldsmith standing.

As I struggled to make sense of my unfamiliar place in the universe and to come to terms with my sorrow, one certainty seemed to wrap itself comfortingly around me, as if I'd slipped on a well-worn flannel shirt on a cold morning. I would once again write a book about my family. The family had been reduced to all but nothing, but I would do my best to see that it lived on. I would tell the story of my Grandfather Alex and Uncle Helmut, of their journey on the

St. Louis

and their unhappy odyssey through France. Having lost my father and my brother, I would write about my father's father and his brother. Perhaps I was trying to cling to what had slipped away forever. But whatever the source of my decision, I told myself that I would write the book so that it could be completed by the day I, too, reached sixty. I didn't have much time.

I began by paying several visits to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the immense building on the National Mall in Washington, solemnly designed to suggest a concentration camp. I knew that Alex and Helmut had landed in France in June 1939 and that they'd arrived in the Rivesaltes concentration camp in January 1941, but where and how they had passed those interim eighteen months remained a mystery.

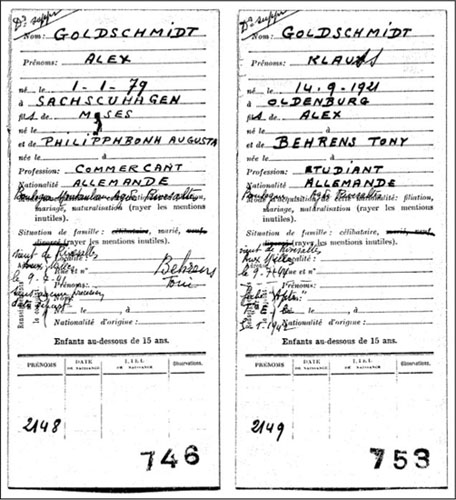

In 1941, a helpful French functionary filled out these cards that, seventy years later, provided me with invaluable clues regarding my grandfather and uncle's journey through France. Note the handwritten cities listed just below the line marked

Nationalite.

(Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

But then, while poring over microfilm in the museum's library, I made an intriguing discovery. Examining the information in the section given over to Camp de Rivesaltes, I found the cards that an efficient French functionary had filled out to mark the transference of my grandfather and uncle from that camp to their next destination, Camp des Milles, in July 1941. In addition to noting their names, hometowns,

professions, dates of birth, and the names of their nearest relatives, my unknown helper of seven decades earlier had also written in the words “Boulogne,” “Montauban,” “Agde,” and “Rivesaltes.” Boulogne and Rivesaltes I knew, respectively, to be the names of the town where Alex and Helmut had landed in France and the hellish camp near the Pyrenees, but what of the other two?

A little breathlessly, I called over a museum staffer. She furrowed her brow and then brightened. “Why, Agde was another camp, also in the south of France, near the Mediterranean. And Montauban . . . that's a town in the south of France, near Toulouse. Those must have been your relatives' last known addresses before their arrival in Rivesaltes!” Montauban was not a concentration or refugee camp, but it was possible that my grandfather and uncle had been held there, maybe hidden there, after the start of the war in September 1939. More mystery.