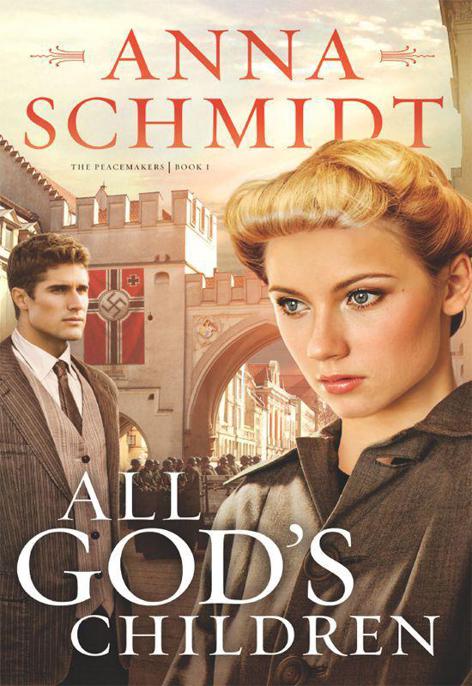

All God's Children

Read All God's Children Online

Authors: Anna Schmidt

Tags: #Christian Books & Bibles, #Literature & Fiction, #Romance, #Historical, #United States, #Religion & Spirituality, #Fiction, #Religious & Inspirational Fiction, #Christianity, #Christian Fiction

© 2013 by Anna Schmidt

Print ISBN 978-1-62029-140-5

eBook Editions:

Adobe Digital Edition (.epub) 978-1-62416-469-9

Kindle and MobiPocket Edition (.prc) 978-1-62416-468-2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted for commercial purposes, except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without written permission of the publisher.

All scripture quotations are taken from the King James Version of the Bible.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any similarity to actual people, organizations, and/or events is purely coincidental.

Cover design by Kirk DouPonce, DogEared Design

Published by Barbour Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 719, Uhrichsville, OH 44683,

www.barbourbooks.com

Our mission is to publish and distribute inspirational products offering exceptional value and biblical encouragement to the masses

.

Printed in the United States of America.

“This is a call to the living,

To those who refuse to make peace with evil,

With the suffering and the waste of the world.”

Algernon D. Black, former senior leader

,

New York Society for Ethical Culture

M

UNICH

O

CTOBER

—D

ECEMBER

1942

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

B

eth Bridgewater rushed into the cramped foyer of her uncle’s third-floor apartment. Her uncle was a professor of natural sciences at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, and his collection of files and notebooks for his research projects cluttered every available space. Beth moved a stack of books so that she could shove her feet into the slippers tradition required her to put on the minute she entered the house. “I’m home,” she called.

Of course, this wasn’t home. Not really. This was Germany— Munich, the capital of Bavaria and headquarters of the Third Reich. Home was half a world away in Wisconsin. Home was a farm where her parents lived just outside of Madison. Home was the Quaker meetinghouse where she and her friends and family gathered for all of the important and mundane events of their lives. Home was certainty and safety where at any time day or night she would not have to scurry for the protection of the cellar beneath the ground-floor bakery should the air-raid sirens sound.

Home was where she should be—should have been ever since Germany had declared war on the United States. But Germany might as well be the Land of Oz for all the good it did her to think of returning to the United States. She would never forget the day she arrived in Munich and stepped off the train. Everything she saw or smelled or heard was as foreign to her as the language. But at the same time it was all so exciting. She truly began to believe that living in Germany could turn out to be a grand adventure. Little did she imagine that a few months of summer would stretch into eight long years.

As an American still living in Munich in 1942 after America had joined the war against Germany, she kept a low profile. She helped her aunt with the cooking and cleaning as she cared for her eight-year-old cousin, Liesl. She chose her associates with care. She could not afford to come to the attention of the authorities, although more than likely they already were well aware of her presence in their midst.

As if being American were not enough, she and Uncle Franz and Aunt Ilse—who, like Beth’s mother, were also natives of Bavaria—were members of the Religious Society of Friends, or

Freunde

as they were known in Germany.

“I’m home,” Beth called out again as she unpinned her hat and fluffed her wispy blond bangs. She heard movement in the room just off the foyer that served as her uncle’s study and assumed that Uncle Franz was within earshot. “Such an incredibly lovely day,” she gushed as she set her shoes aside. “It reminds me so much of autumn in Wisconsin, and I have to admit that on days like this I find it impossible to believe that…”

She had been about to say that surely on such a day there could be no place for war and discord, but the door to the study opened, and a stranger stepped into the hall. In the early days after she’d first arrived from America to live with Uncle Franz and Aunt Ilse, she might have finished her statement without a thought. But that was before.

She was so very weary of the need to always measure everything in terms of

before…

.

Before

a friend had been interrogated and then fired from his job and evicted from his apartment because he had dared to make some derisive comment about the Third Reich.

Before

Ilse had begun taking to her bed, a pillow clutched over her ears whenever the jackboots of the soldiers pounded out their ominous rhythm on the street below their apartment or passed by in perfect lockstep while the citizens of Munich cheered.

Before

an apartment in the building two doors down the block had been raided in the night and the occupants taken away.

Year by year—sometimes month by month—things had changed but oddly had also stayed the same. Other than the matter of people being rousted from their homes and simply disappearing in the dead of night, Munich was little different than it had been the summer she arrived. Neighbors went about their daily shopping and errands, chatting and joking with one another as if those people who had vanished from one of the shops or apartments on the block had never existed. Children who had once attended school and played together with no thought for ethnic heritage now flaunted that heritage by wearing the brown shirts of the Hitler Youth or, in some cases, forcing others to wear the crude yellow star that marked them as Jew.

Beth’s first reaction on seeing this stranger in their apartment— this stranger in uniform—was alarm. Was he here to question them? Uncle Franz had been called in for questioning several times—mostly because he had refused on religious grounds to sign the required oath of allegiance to the government. He was also under scrutiny because he taught in one of the more outspoken departments at the university. Every time he was summoned for an interrogation, Beth’s aunt suffered. The debilitating nervous anxiety that Ilse Schneider had developed shortly after giving birth had not improved with time and was only exacerbated by the uncertainty they lived with day in and week out.

Had this man come to deport her? The Nazis had a well-deserved reputation for being sticklers for detail—people who left nothing to chance. Even with the war raging, it was not unthinkable that the presence of an American in their midst might draw their attention. Or perhaps something else had happened. Were they all to be arrested? In these times such thoughts were natural—even automatic.

“Hello,” the man said in accented English. He wore a medic’s insignia on his military jacket and held his military cap loosely in one hand. Although he was several inches taller than she was, he seemed to be looking up at her from beneath a fan of lowered lashes. She was pretty sure that he wasn’t more than a year or so older than she was.

“Elizabeth, this is Josef—Dr. Josef Buch,” Uncle Franz explained as he came to the door and stood next to the soldier. “I found the citation we were looking for, Josef.” He held a book, his forefinger marking a page, his wire-rimmed reading glasses balanced on his forehead. His hairline had receded a little more every year since Beth had first arrived to answer his plea for help with his sickly wife and overactive daughter. His shoulders were a bit more stooped, and he looked a good deal older than his fifty years. He hid his worrying about his family, his job, the future as well as he could, but it was taking a toll. Although Beth had offered repeatedly to return to America, her uncle would not hear of it. “I need you here,” he always said as he cupped her cheek with his palm. “We all do.”

As she waited for him to explain the doctor’s presence, she studied him closely for warning signs that she should be concerned or remain silent. But he looked more relaxed than Beth had seen him in weeks. Clearly something about this stranger had put her uncle completely at ease—had even lifted his spirits. Once again Beth turned her attention to their guest.

“Grüß Gott, Herr Doktor,”

she said. She kept her curiosity about why the man spoke such flawless English to herself, having been admonished repeatedly by Ilse to say as little as possible in the presence of others and never to ask questions. Instead she took a moment to examine him while her uncle read aloud a passage from the book he carried.