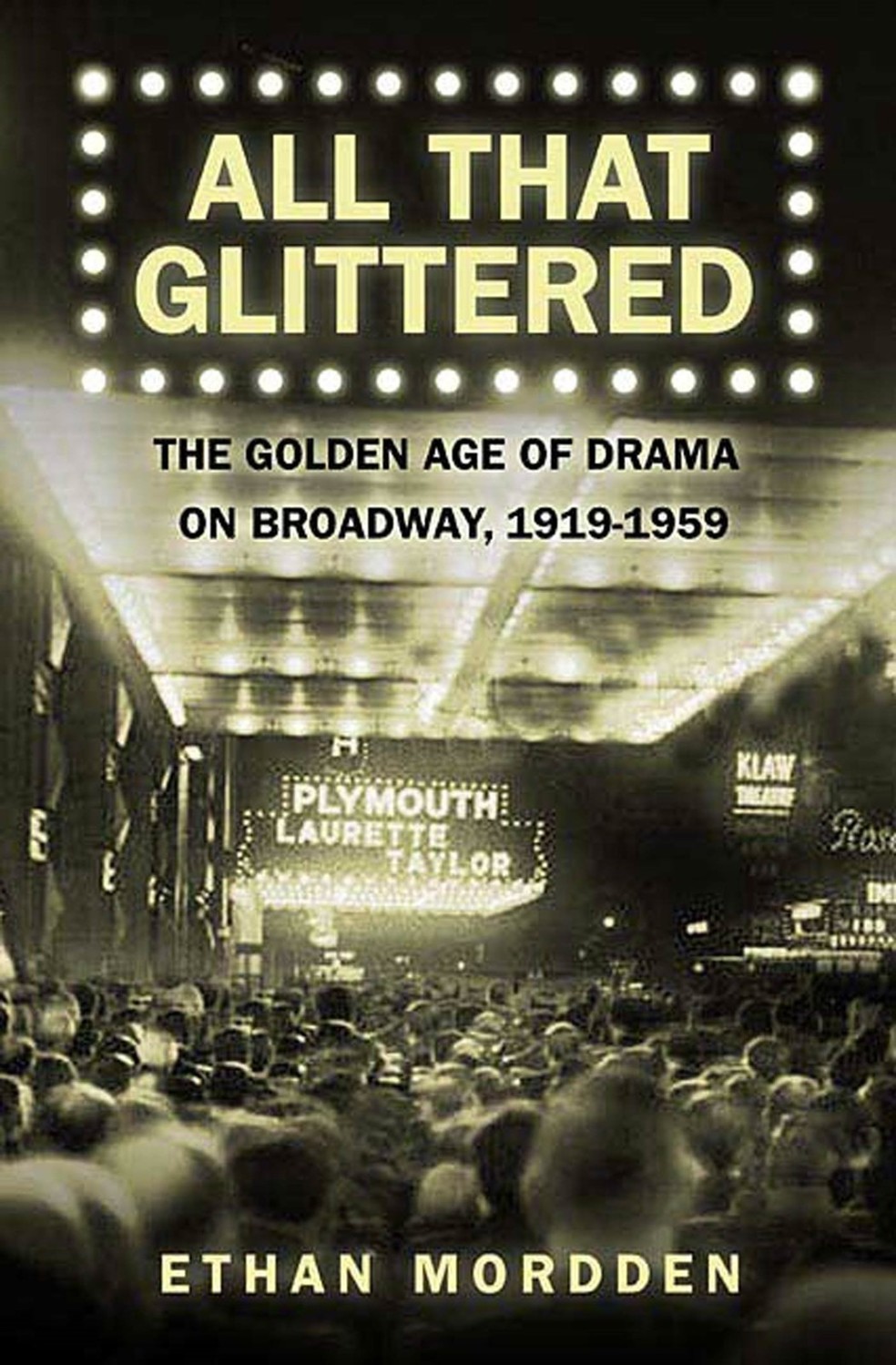

All That Glittered: The Golden Age of Drama on Broadway, 1919-1959

Read All That Glittered: The Golden Age of Drama on Broadway, 1919-1959 Online

Authors: Ethan Mordden

Tags: #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Broadway & Musical Revue

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

2. I’ll Be All Right When I’m Acclimatized: Old Broadway

3. The Rise of Wisecrack Comedy

4. Beauty That Springs from Knowledge: New Broadway

6. The Celebrity of Eccentricity

7. Having Wonderful Time: The Popular Stage

8. We Are Not Here to Rehearse Your Play: The Political Stage

9. Woman and Man: Susan and God and The Iceman Cometh

10. Dogs Are Sticking to the Sidewalks: The Early 1940s

11. Olivier Versus Brando: The Late 1940s

12. It’s About This Doctor: A Streetcar Named Desire and The Crucible

13. End of the Empire: The Early 1950s

14. My God, That Moon’s Bright: Auntie Mame and The Dark at the Top of the Stairs

15. The Great Sebastians Make Their Last Visit: The Late 1950s

Other Works on the Theatre by Ethan Mordden

To Erick Neher

To the staff upstairs at the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center; to my excellent copyeditor, Adam Goldberger; to my wonder-working agent, Joe Spieler; and to my marvelous editor, Michael Flamini.

One cannot do justice to all the famous, important, or even ephemerally interesting plays and people of Broadway during the four decades of its most expansive activity—not in a single volume. Therefore, this is a theme-driven text rather than one meticulously collecting titles and names. All the influential developments in the non-musical American theatre between World War I and the Vietnam Era are here. What is missing—or treated in passing—is a portion of the works and personnel that some readers might expect to encounter.

In fact, this is less a theatre history than an examination of our theatregoing culture in its Golden Age: a time when Broadway and Hollywood enjoyed an extremely stimulating relationship, when the nature of celebrity underwent a provocative evolution, when the national sense of humor changed from folk-rural to urban-minority, and when our playwrights were the archons of social examination, the ones who asked the pertinent questions about how we live.

The symbiosis of theatre and film is especially arresting because it no longer exists in even vestigial form (except for movie stars’ new interest in making pilgrimages to the places of Actors Equity). The most obvious benefit, to Broadway, was Hollywood money, for even a flop might pay off on its sale to story-hungry studios. And Hollywood of course benefited from Broadway’s discovery of new acting and writing talent. However, the two different sources of entertainment were intimate in less apparent ways. For instance, one of American art’s happiest inventions is the screwball comedy. It is entirely a creation of the movie industry: yet the materials were furnished by the stage. As we’ll see, it is as if neither theatre nor film could have managed without the other in this and many other projects.

There is as well a striking change in the meaning of the word “Broadway” in this time. In the years just after World War I, especially during Prohibition but also after, Walter Winchell and Damon Runyon were town criers and “Broadway” meant not only the real estate of theatres from the Garrick on Thirty-fifth Street to Jolson’s Fifty-ninth Street Theatre, nor yet the nation’s highest level of thespian craft—“Broadway” as a guarantee of quality—but rather a culture in West Central Manhattan that fascinated the entire nation. This was a world in which gangsters, prizefighters, and the press mixed with artists, socialites, and the famous. Restaurants and nightclubs were Broadway; the Astor Hotel and certain bars and barber shops were Broadway. The term denoted a belief system of almost lawless independence; and a language we might call Fluent Wisecrack; and a prominence in the very meaning of America that made periodic visits essential to anyone—save politicians—who thought of himself as notable. Much of our narrative art—fiction, drama, and cinema—was set in and around this milieu, because that was where our society was developed and revealed.

Today, that setting is Southern California, just as the young genius of the 1920s who grew up wanting to be a playwright finds in his modern counterpart the would-be moviemaker. Ironically, even after the technology to record and reproduce sound liberated the movies to compete with theatre on an intellectual instead of merely sensual level, it was not till Hollywood made faithful renderings of important plays in the early 1930s that the stage began to lose its prestige superiority and devolve over the following decades into a kind of powerless older brother to the true inheritor. MGM made

Grand Hotel

and

Dinner at Eight

with people like Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Jean Harlow, Marie Dressler, and two Barrymores. Can anyone today name who played the original shows on Broadway?

When Frank Bacon left school at the age of fourteen, his native California counted more jobs to fill than skilled labor qualified to fill them. If not exactly the anarchic frontier of legend, California in the 1880s nevertheless offered opportunity to anyone with—as they put it then—gumption. Young Bacon tried sheepherding, advertising soliciting, and newspaper editing, and even ran an unsuccessful campaign for the state assembly. Then he fell into acting.

It was easy to do at the time, for people went to theatre then almost as casually as they turn on the television today, and playhouses were literally everywhere. Some were operated by resident repertory troupes, the “stock” companies that sustained public interest with a constantly changing bill. Certain theatres in a given region were linked to form “wheels” of companies not resident but traveling as wholes from one house to another every six weeks or so; unlike the stock companies, who played everything, the wheels played host to certain genres, for instance in thrill melodrama or society comedy.

The expansion of the railroad doomed stock and eventually closed down the wheels, for now the “combination” troupe dominated the national stage: one unit of actors giving a single work and touring with all the necessary sets and costumes. A success in this line meant moving from one theatre to the next (with perhaps a hiatus in summer) for months or even years. Along with bookings in small towns and provincial capitals lay the possibility of an extended run in Chicago or New York.

Bacon ended up in one of the last stock companies, in San Jose, for seventeen years, during which he is alleged to have assumed over six hundred roles. One sort of character in particular seems to have caught his interest—the uneducated rustic, innocent of fancy fashion, who somehow gets the better of popinjays and rogues. It was a national stereotype, just then reaching its apex in the career of the third Joseph Jefferson (acting was a family trade), especially in

Rip Van Winkle

(1866). During his galley years in San Jose, Bacon envisioned a vehicle for his own version of the trope, a small-time hotelier named Bill Jones and ironically nicknamed “Lightnin’” for his life tempo, as slow as paste and a kind of objective correlative for his low-key yet fierce sense of independence. No one crowds Bill Jones. “Lightnin’” has wife troubles, money troubles, and to every question a set of deadpan retorts that exasperate all those in the vicinity yet—Bacon hoped—amuse the public. “Lightnin’”’s hotel straddles the California-Nevada border, the state line running through the middle of the lobby: so women can shield their reputations by claiming to be on holiday in California while more truly seeking one of those quickie Nevada divorces.

Bacon called his play

The Divided House,

1

and found no takers. Were managers—the contemporary term for “producers”—leery of a character that had held the stage for over a century, or did Bacon fail to set him off properly?

By 1912, Bacon had made it to New York, then as now the goal of virtually any working actor; but Bacon’s New York was vaudeville or plays of no professional importance. Now forty-eight, he had been acting for twenty-two years and had every reason to assume that he would never be anything more than one of the many who got a modest living out of it but made no mark.

And then Bacon happened to tell the extremely successful playwright Winchell Smith about

The Divided House,

and how nobody wanted it, and how Bacon had sold it to the movies.

“Buy it back,” said Smith. He then rewrote Bacon’s script, and with manager John Golden opened it at the Gaiety Theatre (at the southwest corner of Broadway and Forty-sixth Street, now demolished) on August 26, 1918. The renamed

Lightnin’

was a smash. In fact, Bacon was the star and co-author of the biggest hit that Broadway had had to that time. More important, it was general belief that Frank Bacon

was

Lightnin’. Critics likened his warmth and “business” to that of Joseph Jefferson—who also had had to apply to an extremely successful playwright, Dion Boucicault, for assistance before his

Rip Van Winkle

went over.

Up to

Lightnin’,

the record for a New York run belonged to J. Hartley Manners, whose

Peg O’ My Heart

(1912) held New York for about twenty months. Three other titles (

A Trip To Chinatown

[1891],

Adonis

[1884], and

The Music Master

[1904]) trailed

Peg

by a month or so.

Lightnin’

played New York for

three years,

and, had Bacon got his way, he would have led every single performance. Eventually persuaded to take a vacation, Bacon spent it in the Gaiety Theatre watching his replacement, Milton Nobles, who was getting in shape to head the first national company.

It was as though Bacon feared even momentary separation from the individualizing event of his life. He was a husband and father, yes: who wasn’t, in those days? But in

Lightnin’,

Bacon had created something typical yet unique, a play made of hokum that seemed the most honest good time the public ever had. And as Bill Jones, Bacon topped even Joseph Jefferson perhaps, and he could look forward to playing the show he so loved up and down the country for the rest of his working life. Indeed, they had had no little trouble auditioning Bacon’s successor; Nobles was something like seventy, coaxed out of retirement to save the day.