All That Outer Space Allows (Apollo Quartet Book 4) (16 page)

Read All That Outer Space Allows (Apollo Quartet Book 4) Online

Authors: Ian Sales

I was supposed to be somewhere, he says, I got to make a phone call. Wait here, I’ll be back in a minute, hon.

He hurries off back toward the elevators, leaving Ginny on her own in the corridor, wondering if she’s meant to stand there like a lemon until he returns. And then the doors just a little further along the corridor swing open and a woman with short brown hair, dressed in a white nurse’s uniform and white hose, comes striding toward Ginny, and frowns on seeing her and asks, Can I help you?

Ginny introduces herself but is only halfway through explaining her husband is giving her a tour of the MSOB but has just abandoned her to make a telephone call, when the nurse interrupts, and with a smile asks, He was taking you to the suiting room?

I guess, says Ginny.

Well, it’s this way, come on, I’ll take you. My name is Dee, by the way.

She leads Ginny along the corridor and through a pair of double doors into a white-walled room with several tan Naugahyde armchairs scattered about it. Each armchair faces a large white control-panel festooned with dials and valves and knobs; and between each control panel, a waist-high table stretches from the wall out into the room. Dee waves at a man in white coveralls, he’s standing at one of the tables and Ginny thinks he’s talking to someone lying on the table top before she realises it’s an empty spacesuit.

Hey, Joe, says Dee, this is Ginny, you want to give her a quick run-down of what you do in here?

Ginny Eckhardt, Ginny adds, Walden just had to go make a phone call.

She looks at the spacesuit on the table, and asks, Is that what they’ll be wearing on the Moon?

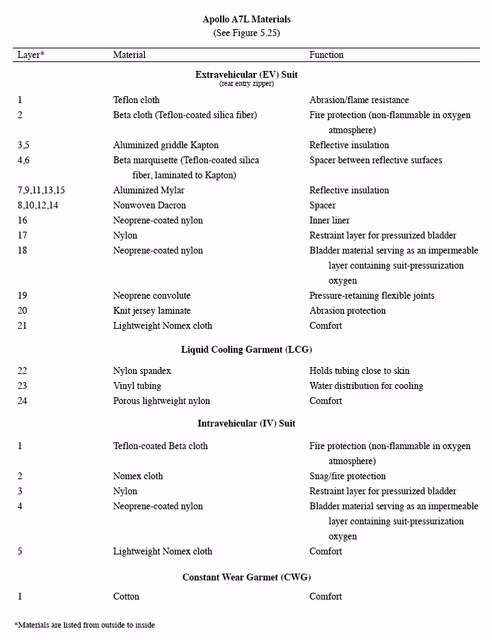

Joe starts to explain the A7L and its twenty-one layers of materials, from the rubber-coated nylon bladder to the Teflon fabric abrasion layer. When he mentions the spacesuits are made by a division of Playtex, Ginny can’t help smiling—and she thinks about bras and foundation garments, girdles and corsets, and the white constricting material from which they’re made, the outer layer of the A7L shares their colour and texture. And the A7L’s innermost layer of nylon too, she’s amused by these manliest of men wearing garments so closely related to women’s underwear. Joe is in the middle of an explanation of the connectors on the front of the torso, and Ginny is listening fascinated, when the doors to the suiting room swing open and Ginny turns and sees Walden poke his head inside, scan the room, scowl, and then withdraw. She makes a face at Dee, puzzled by her husband’s behaviour; but then she turns back to Joe and he has what looks like a fishbowl in his hands and he tells her it’s the helmet and it’s made of polycarbonate…

Joe drifts away after his lecture, and Ginny and Dee chat. They connect immediately, it’s not simply their shared gender in this predominantly male world, or the fact they’re the same age, perhaps it’s the interest Ginny showed in the A7L, in what it takes to put a man on the Moon. For Ginny, it’s partly gratitude at being rescued in the corridor, the chances of someone she knows passing were slim, and she thinks perhaps there are not many at the Cape who would have stopped to ask if she needed help. Emboldened by Dee’s friendliness, Ginny admits she writes science fiction, and Dee mentions a writer who interviewed her years before as research for a novel about a space nurse.

That novel is

Countdown for Cindy

by Eloise Engle, originally published in 1962 in the magazine

American Girl

. I own a copy of the 1964 Bantam paperback. It is the sort of science fiction novel which proves the point of Ginny. In the novel, Cindy, the protagonist, is celebrated by a shocked and astounded media as the first woman into space when she is chosen to accompany a doctor of space medicine to the US Moon base. The book was written, of course, before Tereshkova’s flight aboard Vostok 6.

Countdown for Cindy

is rife with late fifties gender politics—these are not the sensibilities Ginny, who is fictional herself, would write into her own stories, although she has lived with them and not much has changed for the better in the decade since.

There is a scene in Engle’s novel which, for me, is emblematic of the time’s attitudes to women—shortly after arriving at the Moon base, Cindy gets ready for her first shift on duty: “Then she opened her bag and took out fresh disposable undies and a pair of clean slacks. She thought a moment. What a horrid mistake that would be. She folded the slacks, put them away, and took out her crisp white nurse’s uniform and the perky cap. Yes, that was more like it. White hose and white shoes… she looked into the mirror and applied fresh lipstick on her lips. Ready? Not quite. A bit of perfume and a final smoothing of her fluffy hair”. Cindy is expected to

look

like a nurse, no matter how impractical her uniform in one-sixth gravity; and she must look pretty too.

Ten minutes later, Walden sticks his head back into the suiting room, he spots Dee and says, Have you seen my wife— Oh there you are, Ginny.

Before they go, Ginny needs to visit a rest-room, Walden of course has no idea where one for women can be found, but Dee gives precise directions. After washing her hands and fixing her lipstick, Ginny returns to her husband, and she says her goodbyes to Dee, with promises to keep in touch; and then Walden walks Ginny to the elevator, they descend to the first floor, leave the building and he drives her to the visitor center parking lot, where she left her rental. Walden tells her he’ll be round to see her that evening and they’ll go out for dinner, and she wonders if she has brought enough clothes to eat out every night of her stay in Florida. She gets in her car, winds down the window, they kiss through it, and Walden turns on his heel and strides back to his car, while she inserts her ignition key and gives it a thoughtful twist.

It has been like a holiday these days at the Cape. Each evening, he takes her somewhere different to eat—Ramon’s Restaurant, The Moon Hut, Fat Boys Bar-B-Q Restaurant, Bernard’s Surf, Wolfie’s Restaurant… And everywhere they go, they know Walden, they know he’s one of the Apollo astronauts and they tell him he’s going to the Moon for sure. She can see why he frequents these places, it’s not just for the food. Ginny loves the history, the space memorabilia on display—there are wooden plaques naming the Mercury Seven astronauts on the walls of Ramon’s, signed photographs and “flown items” in the other venues.

And having Walden in her bed every night, it’s doing both of them good, the sex is better than it has been for a long time. Walden is more relaxed, he flashes that aviator grin of his more often; Ginny feels wanted, no longer an accessory, but a

partner

. They talk, and it’s silly stuff, trivial chatter, they laugh and joke, they have fun together. Walden, for the first time, tells her a little bit about what he’s doing, and he’s surprised and delighted when she understands some of it.

Remember when I showed you the LM simulator, he says, I thought you were going to fly the damn thing all the way to the Moon.

I wish I could, she says wistfully.

They’re lying in bed, only just covered by rumpled sheets, the lights are off and the room glows with moonlight the same colour as the polished skin of a command module. Ginny smiles indulgently. She rolls onto her side, facing Walden, and props her head on her palm. He is gazing up at the ceiling and he’s talking but she’s not taking in the words. She spent today on the beach, basking beneath the sun, and she can feel the heat she took in radiating from her, she is golden with it, and she doesn’t feel like a member of the Astronaut Wives Club for the first time since moving to Houston, she feels like a

wife

. Grateful, she bends forward and pecks her husband on the lips, silencing him.

#

#

The “couple of days” turns into a week. Ginny has seen all there is to see at the Cape, but she is enjoying her husband’s company too much to want to return to the empty house in El Lago. She explores the surrounding area but there is little of interest, people come here for the beach and the astronauts. She finds a small book store with a reasonable science fiction selection, buys a couple of new paperbacks—one by Kate and one by Marion—and reads them as she lays on the beach, for the first time in her life finding pleasure in pure indolence, enjoying the way the heat soaks into her body, causing her to gently and effortlessly perspire, and, though she would never admit it, she is even gratified by the speculative looks she receives from passing men.

But it has to end, she’s known since the first night it would end, she can’t stay here forever. Walden tells her over drinks in the Riviera Lounge:

The other guys, he says, they don’t like it if the wives stay too long. You have Houston, we have the Cape. You put us off our training.

But I’m interested in all this, she protests.

Yeah, you see, he says, that’s what wrong. I mean, I never said anything about your stories, about your women’s magazines, with their spaceships and robots. I mean, hell, it’s all make-believe, right?

He adopts the serious face he likes to use when he’s about to tell her something he thinks she doesn’t know but is secretly afraid she already does. She has never had the heart to tell him he is usually right to be scared—but marriages survive on the discretion of wives.

You’re like a distraction, Walden tells her; you

are

a distraction. I have to give it one hundred percent, I can’t have anything around that affects my focus.

You have to go back to Houston, he says.

She’s been feeling a need to write, prompted by the two novels she’s just read, and by what she’s learnt here at the Cape, so she’s sort of glad the idyll is over. But it still hurts to be told to go away by her husband.

He reaches across the table, takes her hand and squeezes. It’s been real good, Ginny, he says, having you here, but the holiday is over.

She gives a wan smile, picks up her piña colada and sucks on the straw, but then her eyes narrow as something occurs to her. What about the Apollo 11 launch, she asks, can I stay for that?

In just over a week, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Mike Collins will be heading for the Moon, and four days later they will make the first lunar landing, they will be the first people to set foot on an alien world in the history of humankind.

I think you should go home, Walden says firmly.

Ginny really wants to see the Apollo 11 liftoff, and not on television. But she will not plead, she will not wheedle. There will be other launches. And she

is

missing her Hermes Baby. Her head is full of ideas, baked to a lustrous finish beneath the sun during her hours on the beach, she has written stories in her head as she sunbathed, has dreamt up plots, narratives, settings, and she wants to get them down on paper before she loses them forever.

I’ll book a flight tomorrow, she says.

Walden’s mood abruptly improves, and he grins and lifts his own scotch and branch water and salutes Ginny.

And she thinks, if only

she

were so easy to please, if only spousal obedience were enough to make

her

happy—but Ginny ordering Walden about is almost unthinkable, although there are science fiction stories where women dominate: Francis Stevens even wrote one back in 1918! For now, however, Ginny will have to settle for her husband’s faithfulness.

And she knows she’s richer than many of the other astronaut wives for having it.

#

Ginny’s impromptu holiday has had a salutary effect on her. Back in El Lago, she spends a day cleaning the house from top to bottom, getting down on her hands and knees to scrub the kitchen floor, polishing the faucets in the bathrooms until they shine like the skin of a LM, taking the rugs out into the yard and beating them until her arm aches. She rearranges the kitchen cupboards, emptying them, wiping down the shelves, and then deciding what will now go where. Walden can never find anything, so it doesn’t matter if everything has moved.

Only when Ginny is satisfied the house is as clean as it will ever be—and she marvels at the pride she is taking in her home, and she thinks of the years at Edwards and the dust that covered everything and how some things,

most

things, seemed more important than whether the house was neat and tidy and clean… It’s not just her home however, now she even spends time fussing over her appearance, each morning powdering her face and painting her lips, mascara and eyeshadow, plucking her eyebrows, styling her hair, doing it

every day

; she wears nice dresses, heels that match, keeps her nails shaped and polished… She is well-groomed, and she takes satisfaction in being so.

Ginny’s flying visit to the Cape was also a holiday from Ginny the astronaut wife. That healthy glow she sees in the mirror each morning is not just suntan. But now she is back home, and she has to think about the house and she has to always look presentable, and her head is brimming with ideas for stories she wants to write. For the first time in such a long time, deep in her heart she knows that Mrs Walden J Eckhardt and Virginia G Parker are one and the same person. So she makes herself a jug of iced tea, and she fetches the Hermes Baby and a sheaf of paper from the closet, and still in the white balloon-sleeved blouse and black skirt and waistcoat combination she dressed in that morning she goes to the dining table. She does not need her slacks, she does not need her plaid shirt. (But she does slip off her peep-toe heels.)