All That Outer Space Allows (Apollo Quartet Book 4) (2 page)

Read All That Outer Space Allows (Apollo Quartet Book 4) Online

Authors: Ian Sales

Bob was here, looking for Judy, she replies.

Damn bad luck. He’s going to be grounded for months with that leg.

And that’s all Walden says on the matter.

#

#

Ginny exits the house carrying a tray on which sits a platter of raw steaks. The guys are standing about the barbecue—Scott in a chair to one side, busted leg held out stiffly before him in a cast. Walden is making some point emphatically with jabs of a pair of meat tongs. She stops a moment and watches them, watches

him

, her husband, wreathed in a cloak of grey smoke, her flyboy, in his white T-shirt and tan chinos, aviator sunglasses, that wholesome white-toothed smile. And she thinks, so strange that his parents should name him after a book subtitled “Life in the Woods”…

They didn’t, of course; I did, I named him Walden for Henry David Thoreau’s 1854 polemic. There is a scene in Douglas Sirk’s 1955 movie

All That Heaven Allows

—the title of this novel is not a coincidence; the movie is a favourite, and, in broad stroke, both

All That Heaven Allows

and

All That Outer Space Allows

tell similar stories: an unconventional woman who attempts to break free of conventional life… There is a scene in the movie in which Ron has invited Cary back to his place for a party. While he and his best friend, Mick, fetch wine from the cellar, Cary is at a loose end and idly picks up a copy of Thoreau’s

Walden

lying on a nearby table. She opens the book at random and reads out a line: “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.” Not only is

Walden

Ron’s favourite book, she is told, but he also

lives

it—

Walden Jefferson Eckhardt, however, is indifferent to Thoreau’s book, not sharing his parents’ admiration of it or its message, for all that he is a test pilot; and they see themselves as a breed apart, at the top of the pyramid, men of independence and daring and achievement. Walden stands there with his fellow test pilots—and Ginny knows them all—and though they’re tall and stocky, blond-haired and brunet, craggy-featured and smooth-faced, they all look the same. Cut from the same cloth, stamped from the same mould.

She starts forward, her heels tock-tock-tock on the patio, because for this gathering she’s playing the dutiful Air Force wife and has dressed accordingly. She approaches the men at the barbecue bearing bloody meat for them to char and broil, and they turn carnivorous grins on her, teeth bright through the smoke, eyes invisible behind aviator shades.

Hey, Ginny, let me take that, says Al, reaching out with both hands for the tray, the neck of a beer bottle clutched between two fingers.

She hands him the steaks, then turns to Walden. Chicken next? she asks.

He has interrupted his anecdote because it’s not for her ears. Sure, hon, he says off-handedly.

She’s tempted to ask him what he was talking about, but she’s uncomfortable under the mirrored eyeless gazes of the guys, so she gives a faint smile and tock-tock-tocks away.

The women are sitting about the table at which Ginny likes to write, nursing drinks, their faces powdered and lipsticked, some wearing sunglasses, a couple with fresh hairdos. And it occurs to Ginny there are more stories at that table than there are when she has her typewriter upon it—and they are

real

stories, not the science fiction she writes, which are set on worlds constructed from, and inhabited by, figments of the imagination; nor are they the stories which appear in

Redbook

or

McCall’s

or

Good Housekeeping

, what Betty Friedan calls stories of “happy housewife heroines”—and it’s those very stories which drove Ginny, and no doubt women like her, to science fiction and its invented worlds. Ginny dislikes words such as “prosaic” and “quotidian” because she believes what she writes employs a dimension beyond that, she believes her stories use science fiction to comment on the prosaic and quotidian

without

partaking of it.

But right now the prosaic and quotidian are signalled by a sky like a glass dish hot from the oven and the phatic chatter of four women in bright dresses, the most colour this yard of sparse grass, and its trio of threadbare cottonwoods, has seen for weeks.

Pam looks up as Ginny approaches, leans forward and slides a martini slowly across the table-top. This one’s for you, she tells Ginny.

I still have the chicken to bring out, Ginny replies.

Later, Pam says with a smile. Drink first.

Alison and Connie add their voices, so Ginny takes the free chair at the table and it’s a relief to stop for a moment. She lifts the drink and toasts the other women.

These barbecues are a regular occurrence, though they each take it in turn to play host. Here in the Mojave Desert, the days are bright and blue-skied, endless dust and heat, and so they lead summer lives throughout the year. Ginny sips her martini and lets the chatter of Judy, Alison, Connie and Pam, and in the background the boasting of the men, wash over her. She has maybe fifteen minutes before the steaks are ready and Walden starts demanding the chicken; because when he wants something he expects to get it, she’s here to cater to him after all. Perhaps in private she can make her own demands, set her own limits, but he brooks no dissent on occasions such as this. She takes another sip of her martini and tells herself her “feminine mystique” is for her husband’s eyes and ears only—

Ginny’s attention is snagged by the rasp of a lighter, and she looks up to see Judy put the flame to a cigarette in her mouth. So Ginny leans forward and asks how she is coping with her invalided husband. In response, Judy sucks in theatrically, eyebrows raised and lips pursed, and then expels smoke in a long plume over the table. The others laugh. It is all too easy to sympathise, they are Air Force wives. Ginny abruptly remembers days in Germany, when Walden flew F-86D Sabre jets for the 514

th

Fighter-Interceptor Squadron at Ramstein AFB. For all her open-mindedness, her hankering for new horizons, Ginny found Germany a difficult place in which to live, the contrast between life on the base and life outside, life in the US and life in Europe, too stark, too marked for comfort. She was prolific during those two years, her writing helped her cope.

Walden calls out: Hey, hon, chicken!

No rest for the wicked, says Alison.

Ginny gives an exaggerated sigh, drains the last of her martini and then plucks the olive out of the glass. She pops it into her mouth before rising to her feet.

Later, everyone has repaired to the lounge and the radio is playing quietly in the background. Ginny is sitting on the floor at Walden’s feet when he throws a newspaper down onto the coffee table and says to the other guys, Have you seen this?

Bob leans forward and picks up the newspaper, that day’s

Los Angeles Times

.

What am I looking at? Bob asks.

NASA wants more astronauts, Walden tells him.

Bob looks down at the front page and reads out: “NASA is looking for men. You must be a United States citizen, not over 36 years old, less than 6 feet tall, with a college degree in Math or Science and with at least 1,000 hours flying time. If you meet all the requirements, then please apply.”

Seriously? asks Bob. You thinking of putting your name in?

Yeah, replies Walden. They’ve put, what, a dozen guys up so far? And the Soviets have launched about ten. They’re top of the pyramid now, Bob.

You been keeping track? asks Al (but his grin is a little too knowing).

Ginny is as surprised as the guys, she didn’t know Walden was interested in space. Walden has asked about the X-15 program, she knows that; but he has not been assigned to it.

She hopes her husband applies to NASA, and she hopes he is successful. She likes the idea of being married to an astronaut, certainly what she knows of space exploration she finds fascinating and she’d welcome knowing what it’s

really

like. Ginny reads and writes science fiction, stories about spaceships and alien worlds, but they’re made up, invented. The Mercury program, the Gemini space capsule—they’re real, men have used them to orbit the Earth. They’re

actual

in a way Ginny’s stories can never be.

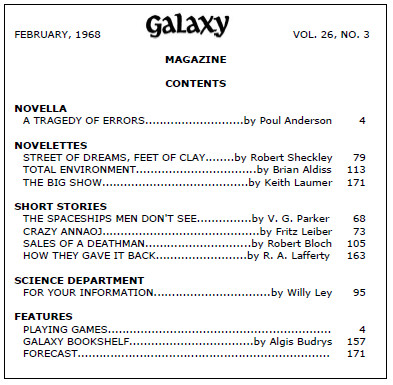

The other wives at Edwards, and their husbands, they don’t know about Ginny’s writing. She hides away the magazines when she has visitors—female visitors, of course; the men simply don’t see them, much as they don’t see anything they consider of interest only to women—and she uses her maiden name as a byline, because she started sending letters to the magazines as a teenager and became known under that name. Ginny keeps her science fiction life separate and secret from her life as an Air Force wife, it’s easier that way. But for all she knows there may well be other subscribers to

Galaxy

and

If

and

Worlds of Tomorrow

at Edwards Air Force Base.

Of course, life here is all about the menfolk, supporting them, providing a stable home life to succour them when they’re not risking their lives. Perhaps that’s why NASA insists on test pilots—or, at the very least, jet fighter pilots. Because their wives are trained to provide the stability the astronauts need in order to risk their lives publicly in such an untried endeavour…

If so, then the joke is on NASA: test pilot marriages fracture before test pilot nerves.

Chapter 2

T-Minus

Walden says nothing about the physical at Brooks AFB or, months later, the interviews at the Rice Hotel in Houston; but for a week after his last trip to Texas he swaggers more than usual. Ginny knows this unshakeable confidence is as much a coping mechanism as will be, should he fail, his subsequent realisation he doesn’t really want it anyway. But she hopes he succeeds, she wishes she could go into space herself. But she knows that, at this time, it’s an occupation reserved for men—no, more than that: reserved for men of Walden’s particular stripe, jet fighter pilots and test pilots. She calls him “my spaceman” one night, it just slips out—she is reading the latest issue of

If

, there’s a good novella in it by Miriam Allen deFord, and Ginny’s head is full of spaceships and spaceship captains; but Walden turns suddenly cold and gives her his thousand-yard stare. He starts to explain the competition is fierce, he won’t know how he’s done until he hears from NASA… but he breaks off, scrambles out of bed and stalks from the room.

Ginny puts the magazine on the bedside table, but her hand is shaking. She sits silently, her hands in her lap, and waits. He does not return. Fifteen minutes later and he’s still not back, so she rearranges her pillows, makes herself comfortable beneath the sheets, and reaches out and turns off the bedside lamp. She has no idea what time it is when he eventually slides into bed beside her, waking her, and whispers, Sorry, hon. She rolls over, closes her eyes and tries to re-enter some alternate world of sleep where marriages are blissful, life itself is blissful, and she is as famous as Catherine Moore or Leigh Brackett.

They wake at 0430, the shrill ring of the alarm dragging them both from sleep. While Walden goes for a shower, she wraps herself in a housecoat and heads for the kitchen. There is breakfast to prepare—coffee to roast, bread to toast, eggs to fry, bacon, pancakes and hash browns. She does this every day, sees off her man with a full stomach and a steady heart. Here he is now, crisp and freshly-laundered in his tan uniform, hungry for the day ahead. He takes his seat, she pours him juice and coffee, slides his plate before him, and then sits across the table and watches him eat as she sips from a cup of coffee. She should be getting up before him, making herself ready, dressed and made up, to greet him when he awakes—but countless past arguments have won her the right to make his breakfast and see him off to work without having to do so. The housecoat is enough.

They kiss goodbye at the door, and he strides off to the Chevrolet Impala Coupe in the carport. Though she wants to go back to bed, there is too much to do, there is always too much to do.

After clearing up the breakfast things, she makes herself another coffee and settles down to catch up with her magazines, she is a couple of issues behind with

Fantastic

, and this issue, the last of 1965, features a novella by Zenna Henderson and stories by Doris Pitkin Buck, Kate Wilhelm and Josephine Saxton.

Later, she will get dressed—and she will dress for comfort, not for appearance’s sake—and she will get out the typewriter and she will work on her latest story. She made the decision years before to incorporate elements of her own life—and, suitably disguised, Walden’s—into her science fiction, so she feels no need to visit libraries or book stores for research. She has a stack of issues of

Fantastic

Universe

,

If

,

Amazing Stories

,

Galaxy

,

World of Tomorrow

in a closet—they are all the research material she needs.

Galaxy

, after all, runs a science column by astronomer Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin;

Amazing Stories

has featured science columns by June Lurie and Faye Beslow since the 1940s. Walden, of course, has a library of aeronautics and engineering texts in the bedroom he uses as a den, and Ginny has on occasion paged through them—not that Walden knows: his den is for him alone and she allows him the illusion of its sanctity; naturally, it never occurs to him to wonder how the room remains clean.