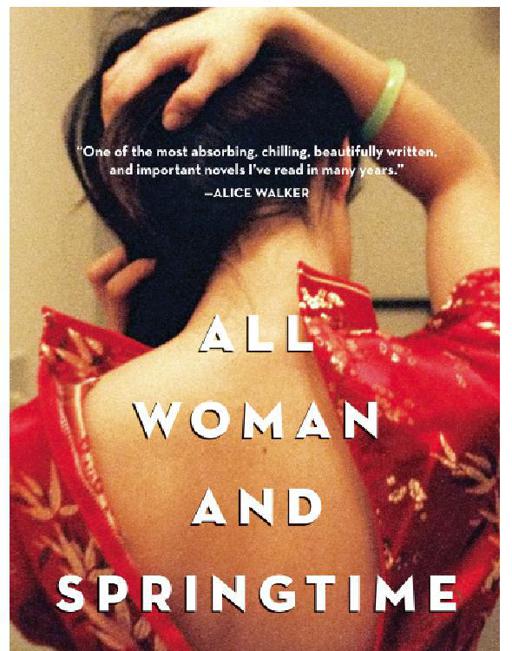

All Woman and Springtime

ALL WOMAN AND SPRINGTIME

a novel by

Brandon W. Jones

ALGONQUIN

BOOKS

OF

CHAPEL

HILL

2012

For my mom, Kathy Jones. May she rest in peace.

Author’s Note

Parts of this novel reveal the physical and psychological traumas associated with human trafficking and sexual slavery. Because of the graphic and mature nature of these themes, the contents of this book may not be suitable for young readers.

A Note on Vernacular

Throughout this novel, I have used the regional word

Hanguk

to refer to South Korea and South Koreans, and the word

Chosun

for North Korea and North Koreans. I apologize in advance to those who are familiar with Korean language, history, and politics, for whom this may be an oversimplification—I wanted to acknowledge this split in Korean identity, but without complicating the story with lengthy explanations, since usage of such terminology is a complex issue.

PART I

1

G

YONG-HO FED ANOTHER PANT

leg into a powerful, old cast iron machine, counting the stitches as she ran a perfect inseam. She watched intently as the needle danced across the rough fabric, plunging in and out of the cloth with methodic violence—she was amazed the fabric did not bleed. It was a paradox of sewing, that such brutality could bind two things together. A distant cloud shifted, liberating a pocket of sunlight that had been building up behind it, flooding the dirty windows high on the factory wall and illuminating her work station in smeared and spotted light. Now the needle glinted as it stabbed. Gyong-ho felt grateful for the light because of its illusion of warmth—she could still see her breath, and her dry fingers ached. The factory was a cold concrete cavern, full of fabric scraps and echoes, a container for damp and chilly air.

She glanced up only momentarily. The Great Leader, Kim Il-sung, and his son the Dear Leader, Kim Jong-il, looked down on her from behind their golden frames. They perched on the wall, smiling, like they did on every wall, looking down on her, watching and weighing her every move. Reflexively she prostrated from within, bowed her head and worked harder. She was not good enough. The portraits filled her with awe and fear.

It is by the grace of the Dear Leader that I live so well,

she recited to herself mechanically.

Gyong-ho was in a nest of sound. The air around her hummed and stuttered with the staccato of one hundred sewing machines starting and stopping at random. Electricity buzzed from lights and machines, and seemingly from the factory women themselves, who were plugged into the walls by unseen tethers. Scissors snipped and clipped at threads in punctuating chops, sharp steel sliding on sharp steel. Holding the sounds together, corralling them, was the shuffling step of the foreman pacing his vengeful circuit of the factory floor, dragging his mangled foot as he walked—thump, slide . . . step; thump, slide . . . step. The sounds were a kind of music to Gyong-ho, helping her focus, occupying a busy part of her mind that was always looking to distill order from chaos.

The pained and lumbering gait of the foreman drew nearer, and Gyong-ho tensed. His powerful body odor preceded him, pinning her to her chair. He was both sour and flammable. He stopped in front of her, and she could hear his raspy breathing, could smell the smoke on his breath. Without looking up at him, she could see his scarred and slanted face, lined with disapproval. He grunted and then labored onward, shuffling away. Gyong-ho exhaled. She knew that his obvious pain was an example of his impeccable citizenship: He walked all day in spite of it for the glory of the Republic.

Foreman Hwang would tolerate no disruption to production, and even restroom emergencies were met with heavy scorn and public humiliation. There was a sign on the wall that read, Eat No Soup. It was a campaign designed to increase production by curbing restroom visits. Unfortunately for Gyong-ho, thin soup had been the only food available that morning at the orphanage. She had tried not to eat too much of it, but she had been hungry; so she danced around her straining bladder, working her hips back and forth in coordination with her sewing.

She worked in rhythm, fast and precise, feeding legs and waists and cuffs into her hungry machine as fast as it could chew them. She worked to outpace a memory that was pursuing her, reaching for her, breathing on her. She was afraid that if she slowed down for even a moment, it might catch up with her, grasping the back of her neck with a black-gloved claw. It was a demon chasing her down a long corridor, his hard shoes echoing, his stride longer than hers, leather hands grazing the little hairs on the back of her neck as they snatched for her, always catching up with her. She kept up a mental race in an effort to evade the memory, her mind in overdrive to distraction.

She chanced a brief look to her right. Her best friend, Il-sun, was finishing a cuff. The seam staggered drunkenly, and one of the trouser legs appeared a little longer than the other. It was a wonder how she could get away with it; but then, she was the pretty one. Sunlight, whenever it shone, seemed to cling to her. Most days it condensed right on her, running in bright rivulets down her body, drawing eyes down the length of her. She was even beautiful with dark circles under her eyes from lack of sleep, and her lethargic motions were fluid—seemingly an open invitation to caress. Her heart-shaped face was set off by pouting red lips and eyes that gazed mischievously from the corners of their sockets. Her skin was flawlessly smooth and her pin-straight hair hung in a black curtain just below her shoulders. In just the last year her body had taken on a new shape that made her hips and shoulders move in hypnotic opposition as she walked. People turned to watch her whenever she glided by, their gaze causing her to radiate even more, to be even more beautiful. Men in particular were affected by her presence, losing their ability to speak, looking both fearful and hungry. Gyong-ho did not like the change.

She worried that Il-sun would again not meet the day’s quota. This would make the fifth day in a row. How long could she go on like this, so indifferent to authority? It was as if she did not understand the consequences of being so . . . individualistic.

They had been working at the factory for less than a year. At seventeen years old, they had been excited to join the ranks of working adults—the novelty of going to the factory every day was a welcome break from the tedium of school. They had felt a sense of maturity as they left the orphanage each morning in their factory uniforms—bright red caps, pressed white shirts, and navy blue trousers—the younger girls gazing at them with awe and respect. Their heads had been filled with images of going to the factory with a feeling of pride and purpose, as if every day was going to be more exciting and fulfilling than the last; after all, this was called the Worker’s Paradise. In a short time, however, all the basics of sewing were mastered, and the job itself did not require much more than that—cut, match, sew, snip, cut, match, sew, snip. Every day, day in and day out, it was the same pair of trousers over and over again. The work transformed quickly from excitement to drudgery, especially under the thumb of the fearsome and cranky foreman.

Finally, a whistle blew and the foreman announced, as if it were against his better judgment, that lunch was being served in the cafeteria. Gyong-ho and Il-sun stood up and, in rigid military fashion, filed out the factory door. Gyong-ho wondered if there really would be lunch, or just the sawdust gruel that was served most days.

The women splintered into small groups as they exited the workroom, and the air filled with chatter. It seemed an odd contrast between the martial atmosphere of the workroom and the casual muddle of the lunch room, as if they were ants that morphed into women and then back into ants again. Occasional laughter could be heard, and a Party anthem played in the background on tinny speakers. Gyong-ho made a break for the latrine. When she returned, she and Il-sun queued up in the cafeteria, waiting for the day’s ration, which turned out to be a small scoop of rice and a slice of boiled cabbage. On the wall behind the service counter was a poster with a drawing of stout

Chosun

citizens handing food across a barbed wire fence to the emaciated and rag-clad

Hanguk.

American soldiers with long noses and fierce, round eyes were holding the

Hanguk

down with their boots, the hands of the

Hanguk

outstretched in desperation. The poster said, simply, Remember Our Comrades to the South. Gyong-ho and Il-sun received their bowls and sat down at a corner table.

“How long do you think we will have to stockpile food for the

Hanguk?

” Il-sun asked, looking despondently at her meager ration.

“Until the Americans stop starving them, I suppose,” Gyong-ho answered. It was widely known that the imperialist Americans were harsh overlords to the oppressed

Hanguk

people, who craved reunification of the Korean peninsula under the Dear Leader. That is why the Dear Leader was stockpiling food for them, asking his own people to sacrifice much of their daily ration to aid the unfortunate people of the South.

“Yeah, but what I wouldn’t give for a bite of pork,” another woman at the table chimed in, not quite under her breath. The whole table fell into a tense, uncomfortable silence. The cold of the concrete room drilled bone deep. Nobody dared inhale. Such a statement was as good as slapping the Dear Leader—it could leave the stain of treason on anyone who heard it.

“But it is worth it for the benefit of our dear comrades to the south,” she added quickly, forcing a smile at the rice balanced on her chopsticks. “It is by the glory of the Dear Leader that we eat so well.”

Conversation resumed. It was a broom sweeping dust under the corner of a rug. Such talk was dangerous.

Twenty minutes later a whistle blew, signaling the end of the midday break. It ended all too soon for the weary Gyong-ho and Il-sun, who were ants once again, marching back into the workroom. They stood next to their sewing stations, feet apart, hands behind their backs. Not all factory foremen demanded such military strictness of their workers, but Foreman Hwang was decidedly old-guard. The shift began with a song in praise of the country’s founder, then the foreman spoke.

“Comrades, I do not need to tell you that there is no higher purpose than serving our Dear Leader.” His voice was low and gravelly, like stones rolling around in a tin can. “It is an honor that he has bestowed upon you, allowing you to serve him in the People’s garment factory. But sometimes I think you do not fully appreciate this gift. Every day I see complacency and laziness.” His eyes landed on Il-sun, and Gyong-ho tensed. “These must be stamped out!” He punctuated the statement by slamming his fist into the palm of his hand, sending a shock wave down Gyong-ho’s spine. She nearly gasped out loud. “We must be prepared for the day when the imperialist dogs, the American bastards and their flunky allies, attack us. Even though we no longer hear their bombs or feel their bayonets in our hearts, we are still at war. They are afraid of the Dear Leader and the mighty

Chosun

army. They are afraid like cornered animals; and like cornered animals they must eventually strike at us, even as hopeless as they know it will be to do so. So we must be prepared for that day. Each of you must ask, ‘What can I do for the Dear Leader?’ ” He let the question hang in the air for a moment to collect drama. “You must do exactly what is asked of you, without question, without complaint.” He paced thoughtfully for a moment.