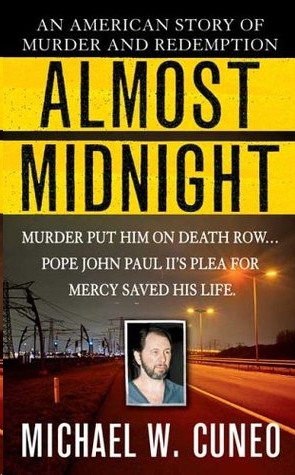

Almost Midnight

Authors: Michael W. Cuneo

ALMOST MIDNIGHT. Copyright © 2004 by Michael W. Cuneo. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information, address Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

BROADWAY BOOKS and its logo, a letter B bisected on the diagonal, are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit our website at

www.broadwaybooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cuneo, Michael W.

Almost midnight : an American story of murder and redemption / by Michael W. Cuneo.

p. cm.

1. Mease, Darrell. 2. Murderers—Missouri—Biography. 3. Death row inmates—Missouri—Biography. 4. Homicide—Missouri—Taney County—Case studies. 5. John Paul II, Pope, 1920—Travel—United States. I. Title.

HV6533.M8C86 2004

364.15′23′09778797—dc21

2003052202

eISBN: 978-0-307-81545-3

v3.1

TO MY SON, RYAN CUNEO

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part I

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Part II

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Part III

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Part IV

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part V

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Afterword

Acknowledgments

PROLOGUE

D

EPUTY JERRY Dodd of the Stone County Sheriff’s Department was headed up Route 13 on a slow Sunday when the call crackled over the two-way. There was trouble near Reeds Spring Junction. A guy named Tom Woodward had phoned the department, saying a frantic woman was at his house screaming that her parents and twenty-year-old nephew had been murdered. She’d found their bodies just a few minutes earlier. She’d found them, at first not realizing they were dead. But then she’d looked—and she’d seen.

Dodd busted north past the junction and veered to the right off U.S. 160. With the dispatcher barking directions, he tore through a maze of rolling backcountry roads, startling a flock of cranes when he came to a skidding stop on the gravel outside the Woodward

place. The woman waiting for him was about thirty, ashen, wearing a jean jacket. Her name was Retha Lawrence. She said she’d found the bodies shortly after two, on a piece of property her parents owned over by West Fork Creek. She’d driven up to the property from the family home in Shell Knob intending to spend the rest of the day.

She told Dodd how to get there. He followed a winding gravel road for a mile and passed through a metal gate, two black-and-orange signs attached to it reading NO HUNTING—NO TRESPASSING. A rough dirt road for several hundred yards, a sharp bend, and he was at the creek, clear and shallow, maybe ten yards across. On the far side, close to where the road picked up again, two all-terrain vehicles sat nudged together, black and shiny blue in the shallow water. On the first, the one closest to Dodd, a woman in pale blue shorts lay sprawled out backward. A man in front of her, in blue jeans and a brown belt, sat with his torso bent far over the side, one arm dangling straight down, the other snagged on the handlebar. On the second vehicle, all Dodd could make out from the opposite bank were a pair of sneaker-clad feet, which seemed tangled up somehow in the front cargo rack.

He cut the engine, got out of the car, and took off his sunglasses. Except for the twittering of birds in the black ash trees, the place was filled with a pale and tremulous quiet. Dodd squinted in the light. Focusing on the first vehicle alone, he could almost imagine it as a favorite photograph in some family album. A couple savoring an intimate moment in a sheltered creek bed—the woman stretching back and enjoying the sun, the man reaching down and running his fingers through the water. Adjusting his gaze to take in the second four-wheeler, the spell was broken. Those feet jutting weirdly from the cargo rack, the body connected to them apparently draped over the other side—nothing dreamily warmhearted about this picture.

Dodd swiped absently at a dragonfly and slowly made his way down the bank and across the creek, the water barely up to his ankles. He walked around the back of the second four-wheeler, the

one with the jutting feet. He stood there, looking. He shut his eyes. He opened them again. He thought about putting on his sunglasses. He heard himself breathing. He looked away across the creek and saw the sun glinting off the windshield of his patrol car. He thought he heard a faint buzzing. He looked down again.

It was a kid, a teenager maybe, wearing gray sweatpants and a black T-shirt, splotched with blood. His outstretched arms and upper torso were resting on the gravel next to the creek. The laces of his sneakers were tied to the cargo rack, keeping his feet grotesquely propped up while the rest of his body flopped down the side of the four-wheeler and onto the ground. The upper right portion of his face, above the eye—it was gone, obliterated, reduced to a pulpy mess, red and gray.

Dodd turned away and looked down the road, lush and green on either side, a trail of blood stretching out along the dirt and gravel from around a nearby bend.

He turned back and looked at the two bodies on the other four-wheeler. He saw what he hadn’t been able to see from across the creek. The woman was wearing a T-shirt decorated with lambs, heart-shaped earrings, and a gold chain around her neck. Her upper torso was caked in a thick reddish-brown. And her head, bent down at a sharp angle toward the rear axle—

Dodd put his fist to his mouth. He thought of the woman, the daughter, back at the Woodward place. He hoped she hadn’t seen everything he was seeing.

—her head, the top and middle of it, was devastated. An angry, flaming V branched out from her brow to the tips of her skull. Inside the V, there was nothing. Inside the V, everything was gone.

The man in front of her, leaning far over the side, was wearing a gray polo shirt, drenched in blood. His brains were leaking out of a gaping hole in his skull, dripping out bit by bit, forming a viscous, red-and-gray puddle on the water’s surface.

Dodd took a slow look around, scanning the brush in every direction. He walked back across the creek, noticing curdled bits of gray flecked with red floating in the water. He wondered why he hadn’t

seen this the first time across. He returned to his car and got on the radio. He was told that help was on the way.

He went back across the creek and followed the dirt road to a scruffy farm property a couple of hundred yards along. A big cabin with a tin roof and wide veranda, pretty recent construction. A white school bus that had seen better days. An old flatbed truck with black cab parked alongside a tractor and a small trailer. A scattering of outbuildings and chicken pens. Nothing out of the ordinary—Dodd had seen dozens of properties much like it up and down the Ozarks.

He stood frozen on the edge of the property, looking and listening. Nothing. No sign of life beyond the groaning of a door joint somewhere, the clattering of stiff branches in the spring breeze.

He went back to the creek. A dozen lawmen were on hand, hat brims turned low, mouths drawn tight. Some were still wearing their church-going shoes. There was the sound of somebody off in the nearby woods, retching.

The sheriff asked Dodd to videotape the scene.

He retrieved a camera from the trunk of a police car and started filming. He captured everything—the three bodies, the gaping wounds, the bloodstained clothing.

He even captured the flies buzzing in and out of the wrecked skulls.

Part I

CHAPTER ONE

G

ROWING UP IN

Reeds Spring, Missouri, Darrell Mease was a tough kid not to like. Ask just about anybody in the small Ozarks town, you’d hear pretty much the same thing. No need to worry about Darrell; R.J. and Lexie’s oldest boy was going to turn out just fine.

There was no reason to think otherwise. Darrell was a kid people enjoyed being around. He loved playing the clown, telling stories, joking, and when he teamed up with his younger brother, Larry, at family get-togethers, the two boys tearing it up, they’d have the entire room in stitches. Best of all, Darrell seemed to know when to draw the line. He loved to poke fun, but never to the point where anybody’s feelings got hurt.

By all accounts Darrell was a good, perfectly ordinary kid. He

was smart enough, scoring decent grades at school, first at the two-roomer up by Mease’s Hollow for a year, then straight through grade twelve at the main school in town, but he wasn’t cut out for spending much time sitting at a desk. On most days, he could hardly wait for school to end so he could duck into the woods behind his parents’ house to hunt for a couple of hours before supper.

Darrell loved the outdoors, hunting and fishing in particular, and he learned almost everything he knew about them from his dad. When he was just two or three, R.J. would take him fishing down by Granny Graves’s place at Jackson Hollow and at nighttime tie him to the car with a piece of trout line. Darrell was prone to walking in his sleep, and R.J. didn’t want him wandering off into the river. One night R.J. woke up and discovered that Darrell had broken loose, but found him tucked safely into bed at Granny Graves’s, just forty yards away. Granny said Darrell had come into her bedroom bragging about fish he must have caught in his dreams.

R.J. was an expert hunter and trapper, and easily one of the best shots in the entire county. He could shoot gray squirrels on the run, and toss walnuts and small rocks into the air and bust them up with his .22 rifle. Darrell admired him for this, but he admired him even more for making the effort to learn how to read so he could keep up with his kids. R.J. had quit school after the third grade, and he’d spend hard evenings working his way through Darrell and Larry’s reading primers, with Lexie helping him. Before long, he was reading newspapers and novels like he’d been doing it all his life.

As with most men of that time and place, R.J. wasn’t much for advertising his feelings. Darrell and Larry were confident that their dad loved them, but it was something they had to infer from the evidence on hand. R.J. would never come right out and tell them. No hugs and kisses, no sweet words or tender embraces. R.J. preferred to express his affection in other ways—by making things for the boys and, of course, by teaching them how to hunt.

Darrell started out hunting with a BB gun when he was six years old, and when he turned ten he graduated to a single-shot .22, which he bought with money he’d made picking walnuts. He’d go

into the woods for hours at a time with his dog, a little mixed-breed terrier named Bull Junk & Iron. He’d learned from R.J. how to bark squirrels, but he’d also hunt groundhogs, rabbits, foxes, opossum, racoons, and quail. He’d bring the game home and his mom and dad would cook it up for supper. The Meases ate a lot of groundhog burgers when Darrell was a kid.

For a couple of years, Darrell and Larry had a pet goat that R.J. had outfitted with a bridle, a harness, and a two-wheel cart. Their cousin Garth also had a goat he liked to ride around the hollow, and one day the three boys decided they’d hitch Garth’s goat to the cart and take a ride over to Aunt Ruby’s and watch some TV. Down by the road, the goat threw a tantrum and upended the cart, spilling the boys onto the gravel and tangling the harness. Some people passing in a car, tourists probably, caught sight of this spectacle—

Oh, look at the little hillbilly boys! How adorable! Can you believe it?

—and started taking pictures. The boys were embarrassed. They were scrambling to get their rig set up right, and Darrell told the people if they’d just wait a second they could get some real good photos. The people just kept grinning and snapping away. The boys eventually got everything straightened out and were on their way again, but they were stopped two or three more times along the road by people in cars wanting to take pictures. Some of the people gave them nickels, one big spender tossed them a couple of dimes, and by the time they reached Aunt Ruby’s they’d pulled in fifty cents—not a bad haul for a few kids just going down the road to watch some TV on the only set in the hollow.