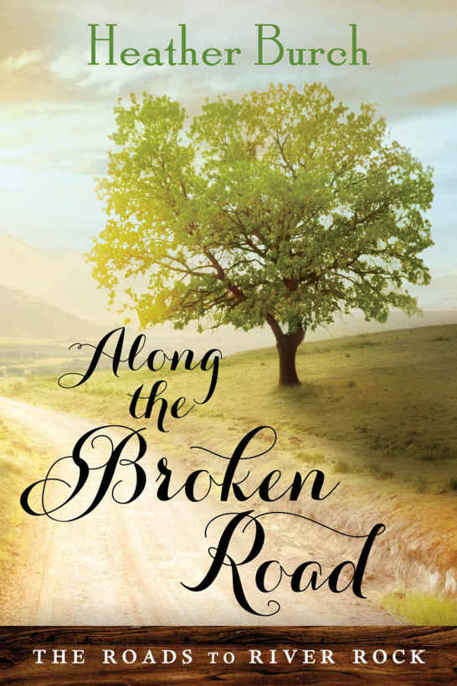

Along the Broken Road

Read Along the Broken Road Online

Authors: Heather Burch

Tags: #Fiction, #Romance, #Contemporary, #Christian, #Family Life

PRAISE FOR HEATHER BURCH

“Heather Burch has proven herself to have such an exceptional storytelling range that one might be tempted to call her ‘the Mariah Carey of romance fiction.’

One Lavender Ribbon

blew my expectations out of the water and then swept me away on a wave of sweet romance. Don’t miss this one.”

—Serena Chase, contributor to

USA Today’s

Happy Ever After blog and author of

The Seahorse Legacy

“Burch’s latest combines a sweet, nostalgic, poignant tale of a true love of the past with the discovery of true love in the present . . . Burch’s lyrical, contemporary storytelling, down-to-earth characters, and intricate plot make this one story that will delight the heart.”

—

RT Book Reviews

on

One Lavender Ribbon

, 4.5 Stars

ALSO BY HEATHER BURCH

One Lavender Ribbon

Young Adult Novels

Summer by Summer

Halflings

Halflings

Guardian

Avenger

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2015 Heather Burch

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Montlake Romance, Seattle

www.apub.com

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and Montlake Romance are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

ISBN-13: 9781477829875

ISBN-10: 1477829873

Cover design by Laura Klynstra

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014922411

For my dad, Jerry McWilliams, the man who taught me the most important thing we can do while we’re alive is to touch the lives of others. There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t miss you. Heaven is a brighter place because you’re there.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

AFGHANISTAN, PRESENT DAY

Ian Carlisle adjusted the backpack cutting into his shoulder and opened the journal. A light wind pressed against his back; the pressure of what lay ahead pushed against his heart. Off to the right of the base was a valley split in two by a green-banked stream. He sometimes went there in the evenings, boots off, no shirt, and wearing shorts with his dog tags clinking against his chest. After today, he’d return to American soil, where he could wade in water without the likelihood of a firefight. Ian touched his hand to the journal. With the base still quiet, he began to read.

I see you standing at the riverbank, your head tipped back, arms outstretched. The sun warms the locks of your golden hair. Does it warm your heart too? Or is it cold? That spot within your chest where you carry the hopes you dream and the pains you’ve suffered. But you aren’t bitter about those hurts. You’re strong. You welcome life. It’s absorbed by you, your grace, your beauty, that spark that only you have. And as I stand here watching I wonder if you’ll even remember me. Maybe I have no right to ask for a place in your heart. And yet, nothing will keep me from it. Nothing will keep me from reaching out to you. I can only pray your heart will hear me and you’ll reach toward me as well.

Ian wiped the moisture from his eyes and closed the journal. Why that specific page haunted him, he couldn’t say. Unfulfilled promises, he supposed. Broken dreams, the things a person planned to do, proposed to do, but never saw them through. Maybe there was a place in heaven where all the broken dreams littered a floor, reaching from side to side like a giant sea of disappointment and missed opportunities. There’d be a few with his name on them, for certain. Drawing a deep breath, he forced his attention to the world around him. The army base stretched before him anchored by tall mountains and what an Oklahoma boy would call tropical vegetation. It remained quiet for late morning, but that suited him fine. He needed a few seconds to adjust to what was happening. In essence, he was stripping off one coat and putting on another, the coat of a civilian. He hadn’t done that in years and wasn’t sure how he’d be at it. But fear was a useless thing. So he chose not to dwell on the what-ifs. A voice from behind took him by surprise.

“You Carlisle?”

“Yes sir.” He turned to greet the man dressed like him in shades of gray-brown.

“All you got?” The soldier hoisted one of Ian’s bags.

Ian grinned. “Like to travel light.”

The guy tossed it into the back of the Humvee and motioned for Ian to get in on the other side. “Guess I’d leave all my junk here for a ticket home.”

“No doubt.” And that’s when it hit Ian that he really, actually,

truly

was going home. It had seemed like a prank until now. Getting his paperwork, packing his belongings, all felt surreal, like someone would wake him at any moment or tell him, “Oh, sorry. We made a mistake. You have to stay.” His head knew he was leaving, but his heart hadn’t assimilated it yet.

In less than forty-eight hours he’d be stateside. And that’s when the real war would begin. The biggest mission of his life lay before him. And after two years in Afghanistan, that was saying something.

“Someone waiting for you back home?” the driver asked as he angled the vehicle toward the gates leading Ian away from base. This would be the last time he saw it. The last time he rode this specific bumpy road . . . away from one life and toward another.

He had to smile. “Yes sir.”

“Good for you.”

Ian peered at him across the Humvee. “I didn’t finish. Yes sir, she just doesn’t know it yet.”

CHAPTER 1

Charlee McKinley had been painting when she got the news her father had been killed. His funeral was a who’s who of military elite complete with majors, colonels, even a general offering their condolences. Everyone liked Major McKinley. Everyone except Charlee.

On the one-year anniversary of his death, she jumped into the lifted Jeep she used for working the grounds and drove it through the creek bed to her favorite spot on the entire property. The sun rose before her, lighting the landscape and painting the shadows with color. Night animals scurried back to their homes, a possum crossing the clearing and disappearing into the edge of the woods that framed Charlee’s spot. She grinned when she saw the chubby animal as it waddled into the tree line. The thing that didn’t make her smile was the fact that now, one year later, she still didn’t know what to do with her father’s ashes.

Off to the right, beyond a smattering of uneven evergreens, Charlee could see the shoreline of Table Rock Lake shimmering with the fresh morning light spilled across it. Sometimes in the early morning before the sun rose and when there wasn’t any fog rolling off the water, she could see beyond the lake to the lights of River Rock, Missouri. The sound of gentle lake waves crashing onto the rocky shore filled her ears. The constant hum was one of her favorite complements to the Ozark Mountain landscape and so different from the violent and tumultuous waves she’d seen on the East Coast during a college spring break she’d rather forget. Those waves were invasive. These were in harmony with the world around them. And harmony was something Charlee held dear.

Harmony

wasn’t

what she felt when her mind drifted back to the urn perched on her fireplace mantel. Why her father hadn’t given the task to one of her brothers, she couldn’t fathom. Maybe it was some sick final joke. She thought about this as she hopped out of the Jeep and moved to the oak stump where she liked to sit. Two giant oaks had once anchored the spot, but one fell to disease and now offered her a seat while the other massive oak offered shelter from the rising sun.

Had it been a joke?

No. Her father had never joked when he was alive; it wasn’t likely he’d begin now. And it’s not that she hadn’t loved her father. She had. Of course she had. She just didn’t like him very much and the feeling was mutual. They were two people at opposite ends of the spectrum, separated by everything that made each who they were. They coexisted in a household after her mother died. They were cordial. Polite. Like strangers.

Now he’d been gone a year. Shouldn’t her world have changed? Been different somehow? Yes, she was a grown woman, but shouldn’t there be a longing for him? Instead there was a longing for all she’d never

had

with him.

When the first beads of sweat broke out on her forehead, Charlee left her perch on the tree stump and started toward the Jeep. The sun was a burning ball above her, promising yet another scorcher of a day. It had been unseasonably muggy and that made the artists cranky.

Charlee ticked off the list of chores in her head, turning her thoughts far from her father and to the world she loved, the artists’ retreat she’d named after her mom. Her mother and she had planned it before her mother’s illness took her life. At twelve, Charlee’d made a promise she’d see it through. And Marilee McKinley had believed her. She’d touched her cheek and said, “You’ll do it, Charlee. I know you will.” And then her glassy eyes closed. Charlee knew that wasn’t the last time she’d seen her mother alive, but it was the last real memory. And she kept it locked in a beautiful box inside her heart. The artists’ retreat was a gift of hope to a little girl who would grow up without her mother to help her learn to wear makeup, to help her understand why boys acted so strange when they liked you, to snap pictures of a prom dress. This was her mother’s way of giving her something to cling to. Something they’d share. Forever, even when death separated them.

Charlee cranked the motor on the Jeep and thought about her day, mentally listing things by order of importance. Mr. Gruber needed a bath. The other artists were complaining. He was one of the more eccentric artists who stayed on the property, often working days without sleep and sometimes forgetting trivial things like hygiene. The hot water in his cottage was shoddy at best and this gave him the perfect excuse not to bathe. She really needed to hire a handyman. Number seventeen on her to-do list.

The Jeep slogged through the creek bed and out to the open field where she could put her foot on the gas. The smooth terrain was mostly free of rocks on this part of the property, making it tons of fun to go fast during the rainy season. She could hit the brakes and spin the wheel, making perfect donuts in the mud—which she’d discovered was a great way to de-stress. As she rounded the curve and the compound came into view, Charlee smiled. She saw this same scene day after day, but mornings like this—after thinking about her mom and how pleased she’d be—Charlee couldn’t help but feel a bit of pride herself. The cottages were arranged in a semicircle around an open yard with a giant wooden platform in the center. There were other cabins nestled in the edge of the woods alongside, but this was the hub of the Marilee Artists’ Retreat. A large metal building used for gatherings anchored the platform and cottages, which sat six on the left of it, six on the right. They were spread apart just enough for privacy, but close enough to give one a true sense of community. Which was important for the artists. Artists, in her experience, were mostly solitary people, more comfortable in the presence of brushes and canvas, music and aloneness rather than in the presence of other human beings. This space brought them together, a wonderful gift to give them. Except when Mr. Gruber hadn’t taken a bath.

Charlee spotted a door opening and a flash of white spiky hair with colorful tips. “Morning,” she yelled as Wilma Vandervort propped her cottage door open with her rear end and shook a dust mop. The woman smiled, waved.

“How’d you sleep?” Charlee said, closing the distance to her.

“Like I’d fallen into angel’s wings.” Wilma held the dust mop handle to her heart and hugged herself.

“That’s great, Wilma.”

Wilma and her sister Wynona had come to the colony close to two years ago. They’d planned to stay for a weekend, but the time stretched and stretched and now, here they were fully moved in and with no intention of leaving. The sisters shared a cottage—which Charlee couldn’t imagine in the 800-square-foot space—and both suffered insomnia. She didn’t know their ages, but guessed they were in their mid- to late sixties. “Did Wynona sleep?”

Wilma shrugged. “Don’t know. She’s not up. Sounds like a busy lumberjack in the loft.”

“I’m going to town tomorrow. Do you two want to ride along?” She tried to make sure the artists who’d taken up residency got out and about . . . into the concrete world . . . every now and then. And some of them liked that. Others felt it a chore beyond human comprehension. Wilma and Wynona were social creatures.

“Yes, we’ll go.” She pointed to the cottage at the left corner. “But I’m pretty sure King Edward wants to go to town as well. Said something about needing a haircut and new socks.”

Charlee cast a glance to his cabin. “Well, there’s room for all three of you.”

“Who has dinner duty tonight?”

“You and Wynona.” Charlee grinned.

“Thought so. What about tomorrow night?”

Charlee sighed. “That would be King Edward.”

Wilma grabbed her throat, made a choking sound. “Will it be spaghetti with tuna again?”

Charlee nodded.

Wilma ran a hand over her head; the rainbow spikes sprung right back up after she did. “You know, he only fixes those horrifying meals because he wants out of the dinner rotation.”

Charlee nodded. “And that’s why we all just man up and eat it.”

Wilma’s chin tilted, eyes filling with nostalgia. “It’s good for artists to suffer. It keeps us in a place of vulnerability. The best work is born in vulnerability.” Wilma was a watercolorist. Her pieces were beautiful and delicate as spun sugar. Charlee swore each new work was better than the last. Wynona, her sister, had been a dancer. She didn’t paint or draw or use any other medium to share her emotions, but the stories she told were incredible and she did have a penchant for decorating things with rhinestones. As a young woman, Wynona danced with the USO during the Vietnam War and though the United States took great pride in how safe they kept the USO entertainers, Wynona had a wandering spirit and would slip out late at night with one of the soldiers . . . or sometimes several of the soldiers. Charlee was pretty sure she’d seen much more than the US government would be comfortable with.

“I’ll be out working on the fence line at the edge of the property today if anyone needs me.” It wasn’t actually the edge of the property. It was where her property stopped and her brother’s began. The 200-acre plot had once been a kids’ camp. Her colony took up the girls’ section and a good mile away the boys’ camp lay on the property her mother had left to her oldest brother. His stretch backed up to the national forest, but hers had the prettiest section of lake and the best cabins. Her other three brothers had a piece of the pie, with various structures on each. Her youngest brother, Caleb, had mineral springs on his stretch of land.

Charlee knew why her mother had bought the place. It was for the artists’ retreat they’d always talked about. Something her brothers never did—and still didn’t—understand. Who cared? This was her dream. And she’d never even thought of sectioning any of it with fence until her oldest brother, Jeremiah, told her he was thinking about finally doing something with that chunk of rocky ground. Good fences made good neighbors.

She bid Wilma good-bye and headed back toward the Jeep. Then she remembered. Mr. Gruber. Charlee sighed and angled to his cabin on the far right. A massive spinning metal daffodil caught her attention. The artist who created the giant yard pieces had come here a year back for a retreat. Most artists came to work, using the gorgeous Ozark Mountains as inspiration. But this particular artist, Javier LaFleur—she’d never learned if that was his real name or an eccentric alias—he’d come simply to rest, walk the property, and as he’d called it, romance the muse again.

Charlee understood that. It had been months since she’d painted anything except a mailbox and shutters. She missed it, having a fresh white canvas at her fingertips, opening the tubes and smelling the oil paint. Mineral spirits. At the same time, making a place for other artists to come and be inspired, well, that was priceless. Besides, she wasn’t really a good artist anyway. She’d have time to paint when she found someone to take over some of the responsibilities on the property.

She stepped onto the small covered porch. All the cabins had them and evenings would find artists rocking in the wooden rockers and snapping photos of spectacular sunsets over the edges of the lush green mountains surrounding the retreat. In many ways it felt like a sanctuary, tucked so neatly against what had been dubbed McKinley Mountain. That wasn’t the official name of the mountain that anchored the edge of her property, but the McKinleys had helped pioneer the small town of River Rock that lay only five miles away. Her father’s family,

her

family—generations of hard workers who took more pleasure in a job well done than in having things named after them.

Good folk

, her dad used to call them, referring to his people, those quiet laborers, the silent workers. Her mother’s side of the family was another story.

Old money

, that’s what her dad called them . . . and there might have been a few other choice words.

Charlee knocked on Mr. Gruber’s door. No answer. The screen creaked open and Charlee realized the knob was loose. She’d need to fix that later. Using her one hand to prop the screen open, she knocked again. “Mr. Gruber?”

A muffled sound came from inside. She took that as an invitation to enter. Light flooded the doorway. Deeper in the cabin she heard a yawn, but her eyes hadn’t adjusted. The cabin smelled stale, like old sweat and older food. She’d pick up some air freshener in town. “Good morning.”

The windows were covered with thick drapes so she moved to the front one and pulled it open wide. A hiss came from the bedroom. She dusted her hands. “Oh come on. It’s not that bad.”

He emerged from the bedroom wrapped in a dark green bathrobe that hung from his narrow shoulders. Mr. Gruber was in his seventies, thin as a rail with sunken cheeks and eyes and a patch of springy white hair on his head.

“What’s good about it?” he mumbled. “Other than the beautiful woman who came to greet me?”

Charlee spun and lifted her arms wide. “You’re too kind.”

“Ha! I’ve been accused of many things; being too kind isn’t one of them.” He shuffled over to the kitchenette counter and peered into the coffeepot as if steaming hot coffee would magically appear.

She placed her hands on her hips. “When did you eat last?”

He grunted in answer and opened the coffee can to shake grounds into the filter. He never bothered to measure.

“I saw you got a package from your daughter the other day. What did she send?”

He waved a hand through the air. “Some box of candy from where they’d traveled in the Caribbean.”

“Oh, that’s nice.”

The ancient coffeemaker rumbled to life. “It’s exorbitant. Do you know what it must have cost to send? A box of candy not worth three dollars?”

“It’s a very sweet gesture. She loves you. Just like we do.” Charlee stopped at his feet and planted a kiss on his cheek.

Whew

. He was ripe. “So, did you finish your painting?”

He tossed his thumb toward the bedroom.

Without invitation, Charlee strode into the room and retrieved the sixteen-by-twenty canvas. She propped it on the easel by the front door, where the sunlight could illuminate it.

A hand went to her heart. A beautiful beach stretched across the entire piece. Turquoise water caressed by sugar-white sand, waves rolling gently with the sun peeking from a ribbon of brightly colored clouds. But it was the subject matter in the forefront of the canvas that took her breath. There, a woman with long, dark hair held up a chubby little baby girl, her mouth smiling, her eyes dancing. The woman wore a white dress that played in the breeze you could almost feel, her hair shimmering against the sun and the baby grinning a toothless grin as if the whole world were her playpen. “It’s beautiful.”