America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook (14 page)

Add the orange juice. Bring to a boil, and then allow to simmer for 5 minutes. Add the Worcestershire sauce, liquid smoke, brown sugar or molasses, stock, and the tomato paste.

Allow to cook and thicken for 20 minutes. Add more pepper and salt to taste.

Roasted Turkey Wings with Mushroom Gravy

Norfolk, Virginia

SERVES 4 TO 6

Junell Thompson says her mother, June, cooked this simple dish for her and her brother back in the 70s. “I love turkey wings, but turkey drumsticks and breasts go well with this recipe and are prepared the same way,” she says. “My mother sometimes made the mushroom gravy from scratch, which is the best way, but here is the simple version for today’s busy mothers, which substitutes the scratch gravy with canned mushroom gravy.”

4 large turkey wings

3 tablespoons salt

3 tablespoons freshly ground pepper

2 tablespoons dry rosemary

6 tablespoons unsalted butter, thinly sliced

½ cup water

3 bay leaves

1 cup sliced yellow onions

1 14-ounce can mushroom gravy

Preheat the oven to 370° F.

Wash turkey wings off under cold water, pat dry, and set aside. Season the turkey wings with salt, pepper, and dry rosemary. Set aside.

In a large baking dish or roasting pan lined with foil, spread the sliced butter and pour the water in the base of the dish. Arrange the turkey wings, bay leaf, and sliced onions on top.

Cover the baking dish with aluminum foil and place in the oven. Roast, turning the wings every 20 minutes, until the wings are fork tender—about 1 hour.

Remove the pan of turkey wings from oven. Set aside. In a small saucepan, heat can of mushroom gravy to desired temperature, pour over turkey wings, and serve.

Presidential Cooks

Cooking Truth to Power

BY ADRIAN MILLER

Benjamin Harrison, the twenty-third president of the U.S. (1889–1893), had little use for the culinary stylings of the French chef already in residence at the White House when he took office. He called on his longtime family cook, Dolly Johnson, to take over the presidential kitchen because he favored her “plain dishes.”

Benjamin Harrison, the twenty-third president of the U.S. (1889–1893), had little use for the culinary stylings of the French chef already in residence at the White House when he took office. He called on his longtime family cook, Dolly Johnson, to take over the presidential kitchen because he favored her “plain dishes.”

Adrian Miller is a former special assistant to President William Jefferson Clinton, and a former deputy director of the President’s Initiative for One America. He worked in the White House from October 1999 to January 2001. Mr. Miller is currently researching and writing a history of soul food.

F

or two centuries,

African American cooks have pleased the palates of our presidents. The presidential kitchen has long been a mélange of culinary skill and racial caste. Several American presidents were slave-owning Southerners who transplanted their plantation cooks to the executive kitchen. Beset with high expectations and limited liberty, black cooks consistently displayed their artistry while working, living, and sleeping in the White House kitchen.

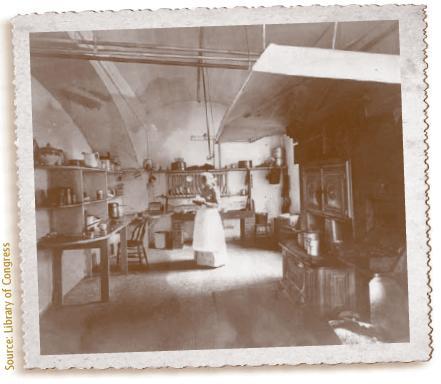

White House Kitchen 1907—African American cooks consistently comprised the ma jority of kitchen workers in the executive mansion, well into the 1960s.

White House Kitchen 1907—African American cooks consistently comprised the ma jority of kitchen workers in the executive mansion, well into the 1960s.

Antebellum presidents also regularly hired classically trained chefs and outside caterers—both free African Americans and Europeans— to cook their meals, particularly when entertaining guests. Mirroring American society at large, the diversity of the White House’s culinary staff created an interesting, though complicated, racial dynamic.

European chefs catered to elite tastes with continental cuisine. These aristocratic dishes graced the table for lavish public affairs, such as inaugural balls and state dinners. Presidents have also retained their own private chefs, many of them African American, to make daily meals for the First Family and entertain guests at smaller affairs. These home-cooked meals featured a variety of regional American specialties, particularly from the American South. As a result, haute cuisine and home cooking thrived side by side, and even rivaled each other, in the White House kitchen.

Haute cuisine often carried more social prestige and captured the public’s imagination, but several presidents have confessed that it was the comfort food of their black cooks that they preferred and praised. George Washington savored the peas, hoe cakes, and fish expertly prepared by Samuel Fraunces, his free West Indian steward. Eddy and Fanny, two enslaved women, regularly ignored the dictates of Jefferson’s French chef and made sure the president got his black-eyed peas, okra, and sweet potatoes the way he liked them.

According to the memoirs of Alonzo Fields, a long-time White House butler, even the aristocratic Franklin Delano Roosevelt relished some homey touches. FDR and Winston Churchill once dined on sweet-and-sour pigs’ feet at a private luncheon. FDR got the recipe from Norway’s Princess Martha, but it was probably prepared by a member of the White House’s all-black culinary staff: Ida Allen (chief cook), Catherine Smith, Elizabeth Moore, and Elizabeth Blake.

20

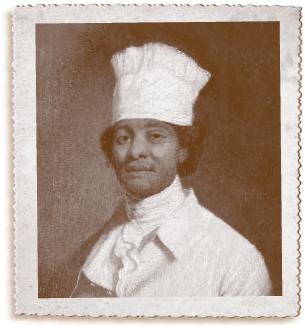

Yet the prestige of cooking for a president was not enough when liberty was out of reach. Enslaved cooks yearned for freedom, and sometimes they got it. Hercules, George Washington’s enslaved cook, disappeared with his son in March 1797 just as President Washington was ending his second term and retiring to Mount Vernon, Virginia. Evidencing her dependence on Hercules, a vexed Martha Washington penned a letter to her sister that said: “[I] am obliged to be my one (sic) Housekeeper which takes up the greatest part of my time,—our cook Hercules went away so that I am as much at a loss for a cook as for a house keeper.—altogether I am sadly plaiged [sic].”

Once formal freedom was secured for African Americans, from Emancipation until the present day, black cooks in the White House have practiced their culinary craft on their own terms. Some got the cook’s job due to a prior stint as a family servant. Shortly after moving into the White House, President William and Mrs. McKinley fired President Cleveland’s cook and hired the African American man who cooked for them in Canton, Ohio. The McKinleys believed that “never was anyone equal to him, and in preparing beefsteak and onions, the favorite dish of the President, he has attained perfection.”

21

Hercules, President George Washington’s enslaved cook.

Hercules, President George Washington’s enslaved cook.

President Benjamin Harrison garnered national headlines when he hired Dolly Johnson, a Kentucky cook, who prepared his meals while he lived in Indianapolis. She quickly made everyone forget about the French cooking of her predecessor, Madame Marcel Pelonard. Johnson’s obituary noted that she was “famous throughout the South for her culinary skill.”

22

Others were recruited as professional cooks. Alice Howard came to the White House staff in the early 1900s and served as the assistant cook for three very different presidents. Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson were united on little else than their love for her corn pone,

23

while William Howard Taft craved her fried chicken.

24

Zephyr Wright, the White House’s last true family cook, served Lyndon Baines Johnson for decades, and they shared a special bond. Zephyr Wright’s life experiences under Jim Crow motivated Johnson to push for landmark civil rights legislation as a U.S. senator, as vice president, and then as president of the United States. LBJ once asked Mrs. Wright to drive back to Texas from Washington, DC. She flatly refused, describing the indignities that she had to suffer of being denied access to food, lodging, and even a bathroom while traveling through Southern states.

LBJ took note and told her story to anyone who would listen—and those who would not. Harry McPherson, a former Johnson aide, remembered one such encounter when then Vice President Johnson pressed his case to an unsympathetic Mississippi Senator John Stennis on the floor of the U.S. Senate.

25

Johnson ultimately acknowledged his debt. When he signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he presented the pen he used to Zephyr Wright, saying, “You deserve this more than anyone else.”

26

Johnson also crowed about Mrs. Wright’s chili and peach ice cream. Just the mention of her chili caused a national sensation. Ladybird Johnson said that requests for the recipe were “almost as popular as the government pamphlet on the care and feeding of children.”

27

Once, Mrs. Wright made an elegant beef hash for a private lunch that President Johnson had with former president Harry Truman and Frank Dobie, a well-known Texas folklorist. Dobie said it was the best he had ever eaten and wrote Mrs. Wright for the recipe.

28

Unsurprisingly, our presidents often celebrated the food because it gave them great comfort. President Jefferson probably said it best when he penned a letter from the White House in November 1802 to his daughter at Monticello seeking the enslaved Peter Hemings’s recipe for English muffins: “Pray enable yourself to direct us here how to make muffins in Peter’s method. My cook here cannot succeed at all in them, and they are

a great luxury to me

(emphasis added).”

29

Samuel Fraunces’ Beef Brazilian Onions

New York, New York

SERVES 8

Heart & Soul

Samuel Fraunces, a free man of West Indian heritage, was a well-known and highly regarded tavern owner in New York City during the American Revolution. During that time, George Washington was a frequent customer of his, and he served him a dish called “onions done in the Brazilian way.” It was one of several delicacies that pleased Washington, and he hired Fraunces to be his steward once Washington became president.

Adrian Miller, an African American historian and student of black presidential chefs, has adapted this recipe to be lighter by swapping out the onions, eggs, and butter in the original recipe for sweet onion, egg whites, and olive oil. For more adventurous cooks, Miller offers the option of substituting bison meat for beef. Either way, this recipe is delicious enough to please any president.

ONIONS

4 medium-size sweet onions (e.g., Vidalia, Walla Walla, or Maui Sweets)

4 egg whites beaten with 1 tablespoon of water

¼ cup of olive oil

BEEF MINCEMEAT MIXTURE

½ pound of ground beef or bison

1 green bell pepper, chopped

1 garlic clove, minced

¼ cup beef stock

¼ teaspoon dried sage

¼ teaspoon dried oregano

salt and pepper to taste

Pass It Down TIP

Where do you find bison? Look no further— Eatwild is the most comprehensive source for grass-fed meat and dairy products in the United States and Canada; lists more than 1,100 pasture based farms that produce beef, lamb, pork, bison, and other meats. Visit them at

www.eatwild.com

.