America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook (25 page)

The bits of papers intrigued me, luring me into the past, and I quickly became an amateur genealogist and learned all kinds of details about my ancestor’s lives, including the birth of my great-great-great-great grandmother in Philadelphia around 1798, and her family’s involvement in co-founding Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia in 1794. I was absolutely fascinated. Eventually, I built a house in Timbuctoo and spent hours captivated by scenic, wooded vistas, roaming rabbits and chipmunks, and an occasional trespassing deer. My 74-year-old mother, Mary Giles Weston, and her various grandchildren—my nieces and nephew—volunteer at what is now an archeological site, unearthing Timbuctoo’s past, managed under the auspices of Westampton Township and Temple University.

As for myself, I like to sit under a 130-year-old tree in our yard and contemplate what life must have been like during the latter years of the 19th century, when that very tree provided shade to my great-great grandfather and his children on hot summer days. For this experience, I will be forever indebted to my cousin Lillian, who gave me a cookbook, as well as a tangible parcel of history and an indelible impression of the meaning of family.

Lillian Jackson’s Fried Green Tomatoes

Covert, Michigan

SERVES 4

Elizabeth “Charli” Bracken gave us this recipe from her grandmother Lillian Jackson, who once had a tomato garden and plenty of green tomatoes. “She would make fried green tomatoes you could smell miles away,” says Ms. Bracken. “When I re-create her fried green tomatoes, my mind clearly takes me back to the wooden porch swing with a pitcher of cold, fresh-squeezed lemonade. I immediately appreciate the good old days when I enjoy this dish.” Ms. Bracken’s version has a dash of cayenne pepper for a little extra heat.

4 medium-size green tomatoes

1 teaspoon salt

4 egg whites

¼ cup milk

1 teaspoon onion powder

1 teaspoon garlic powder

1 teaspoon cayenne pepper

1 teaspoon paprika

½ cup yellow cornmeal

¼ cup flour

1 teaspoon white pepper

½ cup canola oil

Rinse and slice tomatoes in ½ teaspoon of the salt. Allow tomatoes to sit while you prepare the dry and wet mixture.

In a small dish, slightly beat egg whites and milk, add onion powder, garlic powder, cayenne pepper, paprika, and ½ of the teaspoon of salt. Set aside.

In another small bowl combine cornmeal, flour, and white pepper.

Heat the canola oil in a medium skillet on medium heat.

Dip tomatoes in egg mixture, then the flour mixture until completely coated.

Slowly place tomatoes in hot oil and turn each side until lightly brown, about 5 minutes on a side. Place on wire rack set over a cookie sheet or a paper towel-lined plate. Use the remaining salt to season to taste.

Geri Bell’s Stewed Tomato Casserole

Albany, New York

SERVES 6 TO 8

“We use tomatoes that someone in our family preserved, and I usually make it with one large mason jar of tomatoes, juice included,” says Geri Bell of her family’s tomato casserole.“I’m guessing two average-sized store-bought cans will work just as well.”

2 cans stewed tomatoes, 14 ounces each

2 slices day-old bread, cut into 1-inch pieces (use an artisanal-style bread)

1 tablespoon sugar

1/8 teaspoon cinnamon

½ teaspoon nutmeg

1 tablespoon butter, cut into small pieces

Preheat oven to 350º F and grease an 8x8 baking dish.

In a large bowl, combine the tomatoes, sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Mix well.

Add the bread pieces to the tomatoes. Stir well and pour into the greased baking dish. Dot the top of the mixture with pieces of butter. Bake until browned, about 30 minutes.

Serve hot.

BRIDGING DIVIDES ACROSS THE TABLE

When the school segregation issue was taken up by the federal court in Charlotte, the school board was ordered to give people in the community a chance to have their say. I was involved with a group called the Quality Education Committee . . .

There were some very conservative antibusing people, liberal whites, outspoken blacks, and so forth—mortal enemies, you might say—and getting them to associate with one another at all was a big problem. Our idea was to invite representatives of all the groups to a covered dish dinner, thinking that, regardless of race or politics or whatever, Southerners have always been brought up to be nice at the table . . .

. . . I don’t remember what we had to eat. I guess I was too nervous to think about that. Everyone was ill at ease at first, but soon after we sat down you could feel the conversation level rising in the room. It was a very pleasant sound, and it told us that our idea was working.

— Maggie Ray; Charlotte, North Carolina

1985 interview, excerpt from

Southern Food: At home, on the Road, in History

by John Egerton, Ann Bleidt Egerton

University of North Carolina Press, A Chapel Hill Book, June 1993

Taking Back the Table

BY RAMIN GANESHRAM

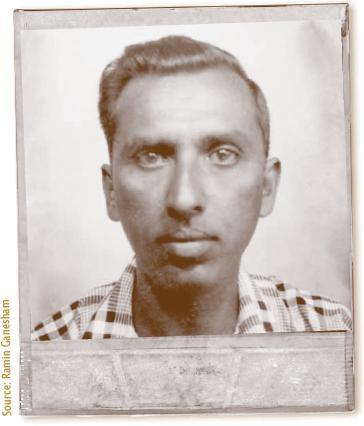

Ramin Ganeshram’s father, Kris.

Ramin Ganeshram’s father, Kris.

Ramin Ganeshram,the co-editor of the

America I AM Pass It Down Cookbook

is a journalist, chef, and well-known authority on Caribbean cuisine. She writes about food from the perspective of cultural history, transition, and progression. Ms.Ganeshram is the author of

Sweet Hands: Island Cooking from Trinidad & Tobago

and

Stir It Up!,

a culinary novel for middle-grade readers published by Scholastic Press.

W

hen my father, Kris, came to the United States

from his home country of Trinidad & Tobago in 1954, he took it into his head to see America. He envisioned driving through amber waves of grain, standing in awe of purple mountain majesties, and being welcomed on the front porches and at the kitchen tables of folks eager to tell their stories and eager to hear his own.

Although raised under English colonial rule, he was a brown man from a brown country whose day-to-day contacts with the nation’s foreign masters were few and far between. He lived in a dark-hued world where separation by color was not exactly foreign, but was reserved for upper classes who might have more cause to butt up against the British ruling class.

As he took off with a white friend, a fellow schoolmate from Brooklyn College— crossing the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan and the George Washington Bridge into New Jersey and heading for points south—my father had no way of knowing that the most common citizen he would actually encounter was Jim Crow.

By the time he told me this story, some twenty years after it occurred, he only spoke with sadness, though at the time I know he raged against having to urinate on the sides of the road and sleep in the car while his friend found warm beds inside welcoming motels. Perhaps in moments of weariness he convinced himself that these indignities were not far different from visiting the bush communities on his native island, where there was no running water, and folks, though welcoming, rarely had an extra bed or cot on which a visitor could sleep.

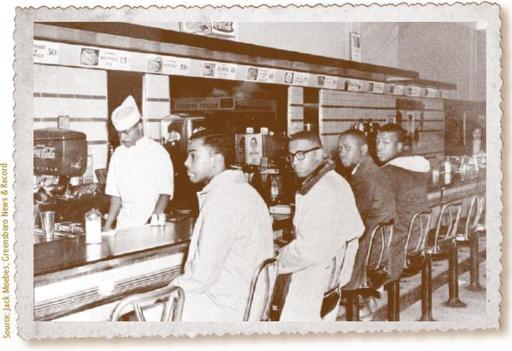

On February 1, 1960, four African American college students sat down at a “whites only” Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, and politely asked to be served. Though the items were available for sale—sodas, coffee, doughnuts—their request was denied and they were asked to leave. They remained in their seats, however. The next day, they returned and asked for service again, despite being sneered at, manhandled, and refused food. Their peaceful sit-down to challenge segregation helped ignite a movement to challenge racial inequality throughout the South.

He coped.

But what he could not cope with, what laid him low three times a day like clockwork, were the mealtimes. It was not simply that he couldn’t find places that would serve him food—his friend could bring the meal out to the car—it was that he was denied the fellowship of the table. Unable to socialize and interact with his fellow man for stretches of miles and days at a time, he retreated into a sense of isolation he had never before experienced. Even back in Brooklyn, where my father had made his new home, the dining table was often a racially charged expanse. One day he and a family friend with whom he was staying went to a local luncheonette to eat. They were the only people of color there. On his way out, he saw the bus boy and waitress breaking the dishes they ate on rather than washing them so they could be reused.

In Trinidad, as in Africa, the Middle East, India, and the ancient world, it is an honor to share your table with a guest. Despite language barriers and differences of religion, tribal communities always held their tent flaps open for a stray visitor. An extra portion of food was always prepared, in case someone in need of fellowship and succor came to your door. In my father’s childhood that golden rule was adhered to, even if it meant feeding the guest the only food you had.

When he returned to New York, after being abandoned on the roadside of Las Vegas when his companion could no longer take the stress of traveling with a colored man, my father became an active member of the NAACP and a civil rights marcher, eating along the route the foods cooked by intrepid church ladies, the cooks who nourished the movement. In fellowship he partook of their meals, a somber but hopeful stepchild of a church picnic or social.

It was, he said, the memory of those meals eaten alone, the dehumanization he felt being denied a place at the table, that spurred him on. Nothing delighted him more than the civil rights protests at lunch counters across the country. It was, to him, the most integral of victories—this taking back a place at the table. It represented not just the toppling of one of the bulwarks of segregation, but the ultimate measure of equality and possibility for understanding—for who can break bread and pass a piece to another person, fingers brushing in the transaction, and remain convinced that one is human and the other is not?