Read American Crucifixion Online

Authors: Alex Beam

American Crucifixion (14 page)

began to grow hard in their hearts and indulge themselves somewhat in wicked practices, such as like unto David of old desiring many wives and concubines, and also Solomon, his son (Jacob 1:15).

In Jacob 2, the Lord speaks even more directly, noting that “David and Solomon truly had many wives and concubines, which thing was abominable before me.” “Nephite Men Should Have Only One Wife” the book sternly warns, and God speaks yet again on this subject to his people:

For there shall not be any man among you save have it be one wife; and concubines he shall have none. For I, the Lord God, delight in the chastity of women and whoredoms are an abomination before me (Jacob 2:27–28).

In the same chapter, the Lord makes the ambiguous statement, “For if I will raise up seed unto me, I will command my people; otherwise they shall hearken unto these things.” For decades, Joseph and other apologists for Mormon polygamy claimed they were “raising up seed” to their Lord, his previous strictures notwithstanding. In a famous letter to nineteen-year-old Nancy Rigdon, who repelled his advances, Joseph simply explained that “whatever God requires is right,” and he was the one entrusted to interpret God’s intentions: “That which is wrong under one circumstance, may be, and often is, right under another.”

Joseph had been confiding his thoughts about plural marriage to his most trusted confederates throughout the 1830s. It seems that Joseph was practicing polygamy without benefit of clergy during that time. “Joseph’s name was connected with scandalous relations with two or three families,” according to his friend Benjamin Winchester. “There was a good deal of scandal prevalent among a number of the Saints concerning Joseph’s licentious conduct, this more especially among the women.” In 1835, rumors of Mormon polygamy were so intense that the Saints’ general assembly issued a statement asserting, “Inasmuch as this church of Christ has been reproached with the crime of fornication, and polygamy; we declare that we believe, that one man should have one wife; and one woman but one husband.” The Saints adopted the measure while Joseph was absent on a missionary trip to Michigan.

It is possible that he married his first “celestial wife” in 1838, although his first recorded plural marriage took place in 1841. Joseph shrouded polygamy in great secrecy, for several obvious reasons. Not only was the practice morally shocking and contradicted by passages in both the New Testament and the Book of Mormon, it was also illegal in Illinois. Nonetheless, defectors and apostates were reporting Joseph’s scandalous views to the world. “Old Joe’s Mormon seraglio” quickly became a stock phrase in the nation’s newspapers, despite the Saints’ heated denials.

Polygamy was not an idea that occurred to Joseph alone. Utopian ideologue John Humphrey Noyes had been propagandizing free love during the 1830s and introduced a system of “complex marriage” at his upstate New York Oneida colony in 1848. At Oneida, all men and women were married to each other, and exclusive attachments were forbidden. It was Noyes who famously observed that “there is no more reason why sexual intercourse should be restricted by law than why eating and drinking should be.” There is no evidence that Noyes and Smith ever met, although it seems likely they would have known about each other from the popular press. Smith

did

meet the notorious Robert Matthews, who claimed to be the reincarnation of the disciple Matthew, returned to earth “to establish a community of property, and of wives.” After a short prison stint, Matthews showed up on Joseph’s doorstep in Kirtland, Ohio, masquerading as “Joshua the Jewish Minister.” After forty-eight hours of intense discussions, Joseph decided that “Joshua’s” doctrine “was of the Devil,” and he escorted him out of town.

did

meet the notorious Robert Matthews, who claimed to be the reincarnation of the disciple Matthew, returned to earth “to establish a community of property, and of wives.” After a short prison stint, Matthews showed up on Joseph’s doorstep in Kirtland, Ohio, masquerading as “Joshua the Jewish Minister.” After forty-eight hours of intense discussions, Joseph decided that “Joshua’s” doctrine “was of the Devil,” and he escorted him out of town.

Smith definitely knew about Jacob Cochran’s doctrine of spiritual wifery at his Saco, Maine, colony, because the Mormons had tried to convert the Cochranites. Future apostle and polygamist Orson Hyde visited a Cochranite community in 1832 and reported on their “wonderful lustful spirit,

. . . because they believe in a “plurality of wives” which they call spiritual wives, knowing them not after the flesh but after the spirit, but by the

appearance they know one another after the flesh

.

In 1841, Joseph discussed polygamy with his Apostles, and the doctrine was formally recorded, albeit secretly, in July of 1843. In the revelation, God invoked the names of the Old Testament polygamists, and continued: “Verily I say unto you, my servant Joseph, that whatsoever you give on earth, and to whomsoever you give any one on earth, by my word and according to my law, it shall be visited with blessings.” In the next to last verse of the lengthy revelation, God invoked the “law of Sarah,” an insidious stricture for women who didn’t want to share their husbands. If a wife refused to consent to polygamy, the revelation instructed, the husband no longer needed her assent to take on other wives.

God also included a special message for “mine handmaid Emma,” whom he correctly imagined might greet the new doctrine with muted enthusiasm:

And I command mine handmaid, Emma Smith, to abide and cleave unto my servant Joseph, and to none else. But if she will not abide this commandment she shall be destroyed, saith the Lord; for I am the Lord thy God, and will destroy her if she abide not in my law (Doctrine and Covenants 132:54).

A decade earlier, God had issued a revelation, through Joseph, that Emma should “murmur not because of the things which thou hast not seen, for they are withheld from thee and from the world” (Doctrine and Covenants 25:4).

God might well worry that Emma would “murmur” against polygamy. Joseph’s scribe William Clayton wrote down the polygamy revelation sentence by sentence in the Prophet’s second-floor office of the redbrick store, while Smith dictated. (The revelation was hardly news to Clayton; Joseph had urged him to marry his first plural wife earlier in the year.) Joseph’s brother Hyrum was the only other person in the small room. The men realized that someone would have to show the text to Joseph’s wife.

“If you will write the revelation, I will take and read it to Emma,” Hyrum assured his brother. “I believe I can convince her of its truth, and you will hereafter have peace.”

Hyrum’s mission failed utterly. Returning from his audience with Emma at the Mansion, he announced that “I have never received a more severe talking to in my life. Emma is very bitter and full of resentment and anger.”

Emma “did not believe a word” of the revelation, Clayton wrote in his diary, noting that she destroyed the text Hyrum had handed her.

Emma hated polygamy all her life, even though there were moments when she reconciled herself to the new theology. For instance, in a gesture that must have tried her soul, she allowed Joseph to marry two pairs of young sisters who lived in the mansion with the Smiths: Emily and Eliza Partridge, and Sarah and Maria Lawrence. Joseph thanked Emma profusely, never informing her that he had in fact married the Partridge sisters two months beforehand, or that he already had sixteen other wives. Right after the marriage ceremony, Emma “was more bitter in her feelings than ever before, if possible,” Emily Partridge recounted, “and before the day was over she turned around and repented what she had done.” Emma “kept close watch on us,” Partridge added. “If we were missing for a few minutes and Joseph was not at home the house was searched from top to bottom and if we were not found the neighborhood was searched until we were found.”

Within just a few months, Emma threatened that “blood would flow” if the marriages were not undone, and the sister wives were evicted. Joseph sheepishly arranged for the girls to board elsewhere in Nauvoo. William Clayton reported that Emma was threatening to sue for divorce, an untenable proposition for Joseph. Despite her many humiliations, Emma remained the “Elect Lady” of the Latter-day Saints and was quite popular among the Mormon rank and file. She was a principal player in the brief history of the Mormon Church. Joseph often mentioned that the angel Moroni refused to show him the golden plates until Joseph was married, and that Moroni specified Emma Hale as the desired spouse. Emma was Joseph’s first scribe and an early and ardent believer in the plates (“I felt of the plates as they lay on the table,” she later told her oldest son) and in the doctrine of the newly restored gospel.

During his nine-month-long jail term in Liberty, Missouri, Joseph and Emma exchanged tender letters. She visited her husband three times, with their children, before being forced to flee Missouri for Illinois. Rather than risk a messy break with his wife of seventeen years, Joseph generally assuaged Emma’s public demands and did his best to conduct his private life in private.

In a famous incident, Emma is supposed to have surprised Joseph and another mansion lodger, the raven-haired poetess Eliza Snow, kissing on a second-floor landing. With her children begging her not to harm “Aunt Eliza,” Emma grabbed Snow by the hair, then threw her down the stairs and out into the street. Snow was said to have suffered a miscarriage as a result. The tale looms large for the Saints because Snow became the poet laureate of Mormon culture, and a grande dame in the Saints’ new Zion of Salt Lake City. A plural widow of Joseph Smith, she married his successor, Brigham Young, and outlived him by a decade. Snow never spoke of the stairway incident, confirming only that she had been the Prophet’s wife and lover.

A Gentile visitor from Carthage, while paying a call on Emma, innocently inquired, “Mrs. Smith, where does your church get the doctrine of spiritual wives?”

Emma’s face flushed scarlet, the guest reported, and her eyes blazed with fury. “Straight from hell, madam.”

EMMA SMITH’S HORRIFIED REACTION TO POLYGAMY WAS THE RULE, not the exception, among the devout Saints. Joseph’s brother Don Carlos said, “Any man who will teach and practice the doctrine of spiritual wifery will go to hell; I don’t care if it is my brother Joseph.” Brigham Young, doggedly loyal to Joseph and his teachings, said that learning about plural marriage “was the first time in my life that I desired the grave.” Apostle John Taylor called plural marriage “an appalling thing to do. The idea of going and asking a young lady to be married to me when I already had a wife!” (Joseph told Taylor that if polygamy is “not entered into right away, the keys will be turned,” meaning Mormons will be denied entry to heaven.) “The subject was very repugnant to my feelings,” Eliza Snow wrote upon learning the doctrine. Don Carlos died without experiencing the Saints’ full embrace of polygamy. Snow and Young accommodated themselves to the new teaching. By 1846, John Taylor had married thirteen wives.

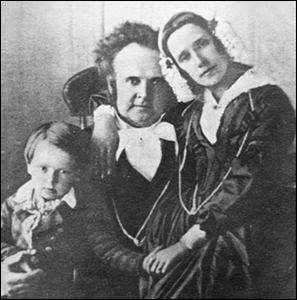

In the early 1840s, Joseph encouraged the apostles to take additional wives, and the inner circle sometimes engaged in dynastic polygamy, or sealed marriages that seemed primarily political in nature. Joseph married Willard Richards’s fifty-eight-year old sister Rhoda, and soon afterward married Brigham Young’s fifty-six-year old sister Fanny. He urged Richards to marry two teenage girls in 1843. Richards’s first wife, Jennetta, died just two years later, “of a broken heart,” according to her son Heber.

A rare 1845 daguerreotype of Willard Richards, his first wife Jennetta, and their son, Heber. Richards married two teenage girls in 1843, and Jennetta died at age 27, two years later and three months after this picture was taken. Heber “always maintained that his mother died of a broken heart,” according to biographer Clair Noall.

Credit: Daughters of Utah Pioneers

Credit: Daughters of Utah Pioneers

Most polygamous marriages were for “time and eternity,” signifying that the man and the woman might have sexual relations on earth (“time”) but also be joined in a larger family at the end of time (“eternity”). The larger the family that gathered to greet the Second Coming, Joseph taught, the greater the heavenly exaltation for all concerned. It is probable that Joseph married Rhoda Richards and Fanny Young for dynastic reasons, for “eternity” only. After Joseph’s death, Brigham Young married many of the Prophet’s widows, including Brigham’s first cousin Rhoda Richards, partly to ensure that the two massive clans would be together for all time.

Other books

Palace Council by Stephen L. Carter

Golden Age (The Shifting Tides Book 1) by James Maxwell

Bear v. Shark by Chris Bachelder

In a Treacherous Court by Michelle Diener

The House of Grey- Volume 3 by Earl, Collin

The Blood Binding by Helen Stringer

The Fear Index by Robert Harris

Exposed by Francine Pascal

Winnie Griggs by The Bride Next Door

To Marry The Duke by Julianne Maclean