American Eve (50 page)

Authors: Paula Uruburu

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Women

As Evelyn describes it, she and Harry inevitably broke apart—aided by the stress of his being in the asylum and her trying to get money from the Thaws for her daily expenses. And then, as if things weren’t bad enough, Evelyn was faced with a terrible crisis that would seal her fate (as far as the Thaws were concerned).

If Evelyn and Harry’s relations were inevitably and understandably strained during the first dismal fifteen months of his incarceration, they reached a critical point when Evelyn announced in early 1910 that she was pregnant. She said her condition was the result of a conjugal visit with Harry several months earlier on a day when both were “feeling sad and lonely.” She also said that this encounter was perfectly possible because of Harry’s money. He vehemently disputed the claim. Already hard-pressed for money, Evelyn now had to endure “the vilest of suggestions”—that she had this child solely to extract money from the Thaws—or that it wasn’t even Harry’s. As each day passed, Harry refused to admit that he was or even could be the father. The situation with the Thaws became unendurable.

“The awfulness of the innuendos” in regard to her unborn child drove her “almost to a frenzy.”

To avoid the anticipated glare of publicity and the Thaw family’s cruelty, Evelyn considered going abroad. Hoping to hide herself and at times wanting simply to forget the name of Thaw altogether, she decided to leave all the scenes of her humiliation and “bury herself somewhere” where she would not be known. Eventually Evelyn landed in Germany, traveling on the ship the

Lusitania.

In October 1910, Russell Thaw was born. As Evelyn wrote in 1915, at the time there were easy ways for her to “find oblivion,” but that she had determined to work out her salvation in such a manner to “avoid the fate which has awaited other women” in similar circumstances and led them to an “ignominious end.” Initially, painfully, and almost tragically, she failed.

While Harry was preoccupied with finding a way to free himself from the asylum, Evelyn came back to New York, seeking a way out of her mounting financial troubles. Amazingly, she reconciled with her mother, who agreed to take care of her infant grandson while Evelyn sought employment. While trying to figure out a way to escape her troubles, Evelyn met a man “who was wholly good, who was neither depraved, prudish nor lax, a broad-minded friend” who recognized how terrible her position was and who helped by setting up some auditions for her in England. In 1911, she left Russell with her mother back in Pittsburgh and sailed for England on the

Olympia.

Once again, fate grabbed at Evelyn. A man named Albert de Courville, a passenger on the ship, recognized Evelyn. He was the manager of the London Hippodrome and very keen to have Evelyn appear there. At first, Evelyn instinctively shrank at the thought of publicity, of “making capital” out of her troubles. But she considered that things were potentially better for her in England than in America, since she assumed people in London had already forgotten about the Madison Square tragedy. Trouble, however, was never far behind her.

En route to England, Evelyn was shocked to receive a wireless message, a Marconigram, that indicated that Harry Thaw had publicly repudiated his son’s paternity in the newspapers. De Courville was sympathetic. In fact, after having come to a tentative agreement about her salary with his agent, a Mr. Marinelli, Evelyn found that Mr. De Courville generously increased her salary for the sake of her infant son. But once Harry’s public dismissal of Evelyn’s claim hit the newspapers in England, her relative obscurity was once more rudely shaken. Two days later she received a phone call from her agent back home, who told her there were problems brewing. The

Daily Sketch

had carried an article that did more than hint that the management of the Hippodrome was taking advantage of her notoriety rather than offering jobs to legitimate artists. There was also a suggestion that she was drawing a fabulous income from the Thaws. The papers made it seem as if she had stepped out of the jury box and onto the variety stage with no intervening time or events.

Disheartened by the thought that she might never be able to get a part, Evelyn considered her limited options and also the far-reaching influence of the press: “I have a respect that amounts to awe for the extraordinary nature of the power of the Press.” Rather than stay in London during what would no doubt prove to be a new wave of journalistic agitation, Evelyn moved on to Paris. As for the issue of Russell’s father, Evelyn wrote, “In reply to those who had the slightest doubt” as to her son’s paternity, “no man who has seen Harry Thaw and Russell can have the slightest doubt as to the child’s parentage.”

Eventually, after a meeting with a reporter from the

Daily Sketch

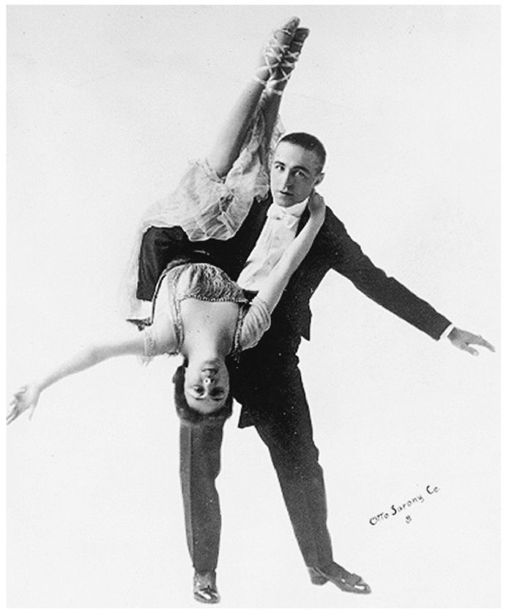

who found Evelyn’s frankness disarming and who then wrote favorably of her desire and the necessity to go back to work, Evelyn was ready to begin again. To that end, De Courville set her up with a dance partner named Jack Clifford, whose experience “ranged from San Francisco to Paris.” Clifford was a handsome, experienced, and muscular dancer who was prepared to literally carry Evelyn through the routines they were

Evelyn with dance partner and

future husband, Jack Clifford, circa 1912.

rehearsing. A dancing master was brought in from Italy to work with the couple on their act as dresses were ordered that would enable Evelyn to do the more acrobatic types of moves that were becoming popular in prewar Europe. The show was

Hullo! Ragtime,

and every day that passed before the opening made Evelyn more and more nervous. Rumors that there would be demonstrators ready to disrupt the opening performance caused the management to come up with what they considered an ingenious plan. They actually cabled America and asked them to send twenty girls of Evelyn’s height and coloring so that when the chorus appeared, the audience would have to guess at which was Evelyn Thaw. But that turned out to be unnecessary as the opposition to her appearing died down before opening night. Now the only problem was whether Evelyn could perform or not.

They had decided to put her into the show unannounced on the Saturday before her scheduled Monday debut. As she watched the revue begin to unfold from the wings, Evelyn’s throat tightened. She sat down behind the scenery near the back of the stage feeling faint. Then, suddenly, the little ritual she used to perform as a

Florodora

girl before going onstage came back to her. It was as natural as breathing.

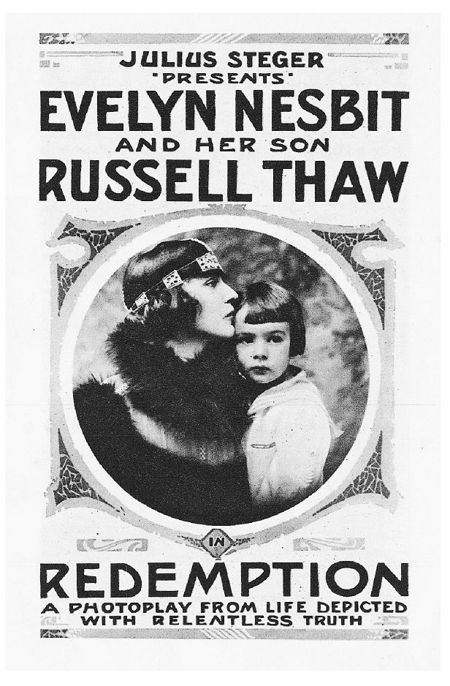

Evelyn and her son, Russell, in a poster

for

Redemption,

1917.

EPILOGUE

The Fallen Idol

A former head of Scotland Yard . . . said that he wished girls, at the age of fourteen, could quietly be put to sleep by the State and allowed to remain unconscious until they were eighteen and ready to become harmless and normal women.

—Frederick L. Collins, Glamorous Sinners

A woman like a country is happiest when she has no history.

—Oscar Wilde

The tragedy wasn’t that Stanford White died, but that I lived.

—Evelyn Nesbit, 1934

s the child-woman whose age seemed intriguingly indeterminate to some and of great consequence to others, Evelyn Nesbit came to New York on the quivering cusp of possibility. Within a year, her captivating face and figure set a new, modern standard of beauty by which all others would then be measured. Acting as a mirror to the era’s deceptively intoxicating and provocative charms, she offered an image of idealized youth and beauty imprinted on the collective consciousness of an America in perpetual and lustful pursuit of “the last horizon of an endlessly retreating vision of innocence.” One need only look at the remarkable Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr. photo taken of a sixteen-year-old Evelyn in 1901 (see page 6) to see the timeless and irresistible quality of a beauty that remains astonishingly contemporary, long after many so-called beauties of the past have faded from fashion. And memory.

It was an image too quickly and easily shattered.

Part Little Eva and part nymphet, proto-feminist and femme fatale, Evelyn Nesbit exposed an entire nation’s sins from the witness box while her own more startling and intimate transgressions were taken up with purple vengeance by the newspapers and promoted from the pulpits as a sizzling cautionary tale. Eventually spread out like a crazy quilt over six decades of the twentieth century, the details of the rest of her life illuminate not only her own personal strengths and weaknesses, but also the brightest and darkest aspects of the collective American Dream she embodied.

But if Evelyn Nesbit’s early life resonated with the intensity and naiveté of Edison’s melodrama that rushed to depict

Rooftop Murder

within a week of the rooftop murder, her life after that ghastly night and the trials that followed continued to move along in fits and starts, capturing in brief but vivid flashes an America always deliriously teetering on the brink of self-awareness. Or self-annihilation.

RÉSUMÉ

After she “rocked civilization” (her own words) for a second time, Evelyn’s consistently mercurial life lurched forward with the same uneasy, haphazard, and artless misdirection it had since she was ten. Although she tried to pick up the shards of her ruined reputation by embarking on a vaudeville career, Evelyn (divorced from Harry in 1915, and no longer Thaw) Nesbit found to her dismay that she could not escape the tentacles of the press or her own “swinging” notoriety. In August of 1913, Harry escaped from the asylum to Canada, and until he was caught and brought back, Evelyn had to fear for her life since the papers were full of Thaw’s “vengeful threats.” In 1916, Evelyn married her dance partner, Jack Clifford (aka Virgil Montani), who was by all accounts an attentive surrogate father to young Russell, but who eventually split with Evelyn, when being known as “Mr. Evelyn Nesbit” became unbearable. She would never marry again. She tested the shadowy waters of silent film, the first of which was produced by the Lubin Company in exotic Fort Lee, New Jersey. Titled

Threads of Destiny,

it was, like the dozen or so films that followed between the years 1914 and 1922, a thinly veiled and self-consciously exploitative depiction of episodes from her own life best forgotten. Only stills of those films remain.

Never far from the front pages or controversy, Evelyn suffered again and again in the court of public opinion. She found herself at the center of a censorship battle over her films when some righteous-minded citizens condemned her for allowing her young son, Russell, to appear in several of them, while at the same time tales of public brawls and ether parties with prizefighters at a retreat in the Adirondacks circulated in the newspapers.

Through the teens and the flaming lawless decade of the twenties, although always threatening to burn out, Evelyn continued to be a commodity, even if she was perceived by most as “damaged goods.” She met with initial if limited success, enough that she could tour the country in her own railroad car for a time. But to the dwindling audiences who watched her rapid decline, she ultimately became merely a curiosity. Unable to live up to her early phenomenal success (and left penniless by the thankless Thaws), Evelyn paid a hard price for her so-called fame. She descended into drug abuse (morphine) and alcoholism, in part to numb the pain she felt from frequent excruciating migraine headaches. She tried several times to take her own life (once by ingesting Lysol), and twice a then teenage Russell was forced to come to her rescue, one time while visiting her in Chicago on Christmas break from boarding school. Her name appeared with colorful regularity in the papers and in gossip columns due to drunken brawls (her nose was broken more than once), nonpayment of bills and evictions, auctions of her clothes and what remained of any furs and jewelry, car accidents, suspected abortions, speakeasy arrests, and associations with mobsters, etc. Her pet boa constrictor, Baby, escaped to the streets of lower Manhattan while she was living and performing in cabarets in Greenwich Village (“He keeps away the bill collectors,” she remarked to bemused reporters).