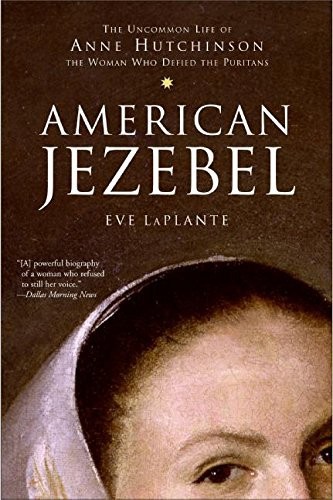

American Jezebel

Authors: Eve LaPlante

The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans

To David and

Rose, Clara, Charlotte, and Philip

You certainly think right when you think Boston people are mad. The frenzy was not higher when they banished my pious great grandmother, when they hanged the Quakers and…the poor innocent witches, than the political frenzy has been for a twelve-month past.

—T

HOMAS

H

UTCHINSON

Governor of Massachusetts

August 1770

1.

Enemy of the State

2.

This Impudent Puritan

3.

A Masterpiece of Woman’s Wit

4.

Strange Opinions

5.

The End of All Controversy

6.

As the Lily Among Thorns

7.

From Boston to This Wilderness

8.

A Final Act of Defiance

9.

Not Fit for Our Society

10.

The Husband of Mistress Hutchinson

11.

An Uneasy and Constant Watch

12.

A Spirit of Delusion and Error

13.

A Dangerous Instrument of the Devil

14.

The Whore and Strumpet of Boston

15.

Her Heart Was Stilled

16.

This American Jezebel

This is a work of nonfiction. All quotations are from the historical record, largely from the lengthy transcripts of the four days in 1637 and 1638 when Anne Hutchinson was brought to trial before the Great and General Court of Massachusetts and then the First Church of Boston. In citing these transcripts I have for the sake of clarity modernized spelling and added punctuation and occasionally emphasis. In quoting the Bible, I use the King James Version except when the quotation is in the words of a seventeenth-century speaker. In those cases the translation is from the Geneva Bible, which Anne Hutchinson and her Puritan contemporaries used.

All sources for the book are listed in the bibliography. All dates are from the historical record, which in the seventeenth-century English world was based on the Julian calendar, created in 45

BCE

by Julius Caesar, rather than on the modern Gregorian calendar, created by Pope Gregory in the late sixteenth century. England and its colonies maintained the old calendar (and its use of March 25 rather than January 1 as the start of a new year) until 1752 as a way of avoiding the innovations of a pope. To modernize any seventeenth-century date in the book, simply add eleven days to it.

I have sought the assistance and advice of many historians, other scholars, curators, and preservationists, who are named in the acknowledgments. If despite all their help the text contains any errors of fact, the responsibility is mine.

But history, real solemn history, I cannot be interested in…. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all.

—J

ANE

A

USTEN

One warm Saturday morning in March, as I let my children out of our minivan alongside a small road in rural Rhode Island, a part of America we’d never visited before, a white pickup truck rolled to a stop beside us. Leaving my baby buckled in his car seat, I turned to the truck’s driver, a middle-aged man with gray hair. “This is where Rhode Island was founded, you know,” he said to me. “Right here. This is where Anne Hutchinson came.

“And you know what?” the friendly stranger added, warming to his subject. “A lady came here all the way from Utah last summer, and she was a descendant of Anne Hutchinson’s.”

For a moment I wondered how to reply. “See those girls there?” I said, pointing at my three daughters, who watched us from a grassy spot beside the dirt road. “They’re Anne Hutchinson’s descendants too.”

In fact, I had driven my children from Boston to Portsmouth, Rhode Island, to explore the place that their eleventh great-grandmother, expelled from Massachusetts for heresy, had settled in 1638.

Anne Hutchinson is a local hero to the man in the pickup, but most Americans know little about her save her name and the skeleton of her story. To be sure, Hutchinson merits a mention in every textbook of American history. A major highway outside New York City, the Hutchinson River Parkway, bears her name. And a bronze statue of her stands in front of the Massachusetts State House near that of President

John F. Kennedy. Yet Hutchinson herself has never been widely understood or her achievements appreciated and recognized.

In a world without religious freedom, civil rights, or free speech—the colonial world of the 1630s that was the seed of the modern United States—Anne Hutchinson was an American visionary, pioneer, and explorer who epitomized the religious freedom and tolerance that are essential to the nation’s character. From the first half of the seventeenth century, when she sailed with her husband and their eleven children to Massachusetts Bay Colony, until at least the mid-nineteenth century, when Susan B. Anthony and others campaigned for female suffrage, no woman has left as strong an impression on politics in America as Anne Hutchinson. In a time when no woman could vote, teach outside the home, or hold public office, she had the intellect, courage, and will to challenge the judges and ministers who founded and ran Massachusetts. Threatened by her radical theology and her formidable political power, these men brought her to trial for heresy, banished her from the colony, and excommunicated her from the Puritan church. Undeterred, she cofounded a new American colony (her Rhode Island and Roger Williams’s Providence Plantation later joined as the Colony of Rhode Island), becoming the only woman ever to do so. Unlike many prominent women in American politics, such as Abigail Adams and Eleanor Roosevelt, Hutchinson did not acquire power because of her husband. She was strong in her own right, not the wife of someone stronger, which may have been one reason she had to be expunged.

Anne Hutchinson is a compelling biographical subject because of her personal complexity, the many tensions in her life, and the widespread uncertainty about the details of her career. But there is more to her story. Because early New England was a microcosm of the modern Western world, the issues Anne Hutchinson raised—gender equality, civil rights, the nature and evidence of salvation, freedom of conscience, and the right to free speech—remain relevant to the American people four centuries later. Hutchinson’s bold engagement in religious, political, and moral conflict early in our history helped to shape how American women see ourselves today—in marriages, in communities, and in the larger society.

Besides being a feminist icon, Hutchinson embodied a peculiarly American certainty about the distinction between right and wrong,

good and evil—a certainty shared by the colonial leaders who sent her away. Cast out by men who themselves had been outcasts in their native England, Hutchinson is a classic rebel’s rebel, revealing how quickly outsiders can become authoritarians. The members of the Massachusetts Court removed Anne because her moral certitude was too much like their own. Her views were a mirror for their rigidity. It is ironic, the historian Oscar Handlin noted, that the Puritans “had themselves been rebels in order to put into practice their ideas of a new society. But to do so they had to restrain the rebellion of others.”

Until now, views of Anne Hutchinson in American history and letters have been polarized, tending either toward disdain or exaltation. The exaltation comes from women’s clubs, genealogical associations, and twentieth-century feminists who honor her as America’s first feminist, career woman, and equal marital partner. Yet the public praise is often muted by a wish to domesticate Hutchinson. The bronze statue in Boston, for instance, portrays her as a pious mother—a little girl at her side and her eyes raised in supplication to heaven—rather than as a powerful figure standing in the Massachusetts General Court, alone before men and God.

Her detractors, starting with her neighbor John Winthrop, first governor of Massachusetts, derided her as the “instrument of Satan,” the new Eve, and the “enemy of the chosen people.” In summing her up, Winthrop called her “this

American Jezebel”

—the emphasis is his—making an epithet of the name that any Puritan would recognize as belonging to the most evil and shameful woman in the Bible. Hutchinson haunted Nathaniel Hawthorne, who used her as a model for Hester Prynne, the adulterous heroine of

The Scarlet Letter.

Early in this 1850 novel, Hutchinson appears at the door of the Boston prison.

This rose-bush, by a strange chance, has been kept alive in history; but whether it had merely survived out of the stern old wilderness, so long after the fall of the gigantic pines and oaks that overshadowed it,—or whether, as there is fair authority for believing, it had sprung up under the footsteps of the sainted Ann [sic] Hutchinson, as she entered the prison-door,—we shall not take upon us to determine. Finding it so directly on the threshold of our narrative, which is now about to issue

from that inauspicious portal, we could hardly do otherwise than pluck one of its flowers and present it to the reader.

Hutchinson never “entered the prison-door” in Boston, as Hawthorne imagines, but she is rightly “a rose at the threshold” of a narrative that is itself a sort of prison.

“Mrs. Hutchinson,” Hawthorne’s eponymous story in

Tales and Sketches,

depicts her as rebellious, arrogant, fanatical, and deeply anxiety provoking. “It is a place of humble aspect where the Elders of the people are met, sitting in judgment upon the disturber of Israel,” as Hawthorne envisions her 1637 trial. “The floor of the low and narrow hall is laid with planks hewn by the axe,—the beams of the roof still wear the rugged bark with which they grew up in the forest, and the hearth is formed of one broad unhammered stone, heaped with logs that roll their blaze and smoke up a chimney of wood and clay.”

Apparently unaware that the Cambridge, Massachusetts, meetinghouse that served as Hutchinson’s courtroom had no hearth, Hawthorne continues,

A sleety shower beats fitfully against the window, driven by the November blast, which comes howling onward from the northern desert, the boisterous and unwelcome herald of a New England winter. Rude benches are arranged across the apartment and along its sides, occupied by men whose piety and learning might have entitled them to seats in those high Councils of the ancient Church, whence opinions were sent forth to confirm or supersede the Gospel in the belief of the whole world and of posterity.—Here are collected all those blessed Fathers of the land….

“In the midst, and in the center of all eyes,” Hawthorne imagines, “we see the Woman.” His Anne Hutchinson “stands loftily before her judges, with a determined brow…. They question her, and her answers are ready and acute; she reasons with them shrewdly, and brings scripture in support of every argument; the deepest controversialists of that scholastic day find here a woman, whom all their trained and sharpened intellects are inadequate to foil.”

In

Prophetic Woman,

a trenchant analysis of Hutchinson’s role in America’s self-image, Amy Schrager Lang observes, “As a heretic, Hutchinson opposed orthodoxy; as a woman, she was pictured as opposing the founding fathers, who, for later generations, stood as heroes in the long foreground of the American Revolution. In the most extreme version of her story, Hutchinson would thus come to be seen as opposing the very idea of America.” A woman who wielded public power in a culture suspicious of such power, she exemplifies why there are so few women, even today, in American politics, and why no woman has attained the presidency.

Unlike most previous commentators, I aim neither to disdain nor to exalt my central character. I strive instead for a balanced portrait of Anne Hutchinson’s life and thought, in all their complexity, based on painstaking research into all the available documents, which are extensive considering she was a middle-class woman living in a wilderness four centuries ago. I’ve had the pleasure of visiting all the sites of her life—in Lincolnshire and London; in Boston, England, and Boston, Massachusetts; and in Rhode Island and New York. In rural England I climbed the steps to the pulpit where her father preached and sat on a bench in the sixteenth-century schoolroom where he taught village boys to read Latin, English, and Greek. I walked on the broad timbers of the manor house that was being built as twenty-one-year-old Anne and her new husband returned from adolescent years spent in London to the Lincolnshire town of Alford to start a family. I touched the plague stone that Alfordians covered with vinegar, their only disinfectant, during the 1630 epidemic that killed one in four of the town’s residents. In the Lincolnshire Wolds I explored Rigsby Wood, where she took her children to see the bluebells bloom each May. Back in the States, I kayaked to an isolated beach on a Rhode Island cove where she lived in the colony she founded, and I rode on horseback through the North Bronx woods to the vast glacial stone marking the land on which she built her final farmstead.

I first heard of Anne Hutchinson when I was a child and my great-aunt Charlotte May Wilson of Cape Cod, an avid keeper of family trees, told me that Hutchinson was my grandmother, eleven generations back. Aunt Charlotte was a character in her own right, a crusty Victorian spinster with Unitarian and artistic leanings, a proud great-granddaughter of the Reverend Samuel Joseph May, a niece of the nineteenth-century

painter Eastman Johnson, and a first cousin twice removed to Louisa May Alcott. Longtime proprietor of the Red Inn, in Provincetown, Massachusetts, Aunt Charlotte served tea and muffins every morning to her guests, including me. Evenings, after the sun set over Race Point Beach, she would nurse a gin and tonic and read aloud from her impressive collection of browning, brittle-paged volumes of poetry. When she recited Vachel Lindsay’s “The Congo”—“Mumbo-jumbo will hoo-doo you…. Boomlay, boomlay, boomlay, boom!”—her aging eyes closed and her ample torso swayed.

Even earlier, curled into an armchair in her little red house across Commercial Street from the inn, hardly a block from the Provincetown rocks where the Pilgrims first set foot on this continent in November 1620, I listened to Aunt Charlotte’s tales of the exploits of our shared, known ancestors. My aunt seemed to favor the abolitionist and minister Samuel Joseph May and Samuel Sewall (1652–1730), the judge who so repented of his role in condemning nineteen “witches” to death in Salem Village in 1692 that for the rest of his days he wore beneath his outer garments a coarse, penitential sackcloth. “For his partaking in the doleful delusion of that monstrous tribunal,” James Savage observed in 1860, Judge Sewall “suffered remorse for long years with the highest Christian magnanimous supplication for mercy.” To me, though, Anne Hutchinson was most compelling on account of her vehemence, her familiarity, and her violent death.

Once I was old enough to pore over the minute glosses around the edges of my great-aunt’s handwritten genealogies, I read wide-eyed of the dramatic contours of Anne Hutchinson’s life. At fifty-one, after her husband died, she moved with her younger children from Rhode Island to New York, to live among the Dutch. When her Dutch neighbors, who often skirmished with local Indians, advised her to remove her family during an anticipated Siwanoy raid, she stayed put. Always an iconoclast, she had long opposed English settlers’ efforts to vanquish Indian tribes. Not for the first time, she risked her life for her beliefs.

As a sixteen-year-old in high school American history class, I listened, ashamed, as my teacher described the religious sect called Antinomianism and Hutchinson’s two trials. The ferocity and moral fervor I associated with her were attributes I disliked in my relatives and feared in myself. Reading about her, I’d learned that one of her heresies

was knowing that she was among God’s elect and then presuming that she could detect who else was too. Since then, I’ve come to see that this view, which her opponents imputed to her, was not hers alone. An excessive concern with one’s own and others’ “spiritual estate” was also typical of her judges. Salvation—who had it, who didn’t—was the major issue of her day, as it may be, in various forms, today.

In my high school classroom I raised my hand despite my adolescent shame. Called on by the teacher, I blushed and said that Hutchinson was my great-great-great…great-grandmother. The teacher’s bushy white eyebrows rose in an expression that I interpreted as horror. Not long ago, though, I ran into him and recalled the scene. I was wrong about his reaction, he said. It was more like awe.

Now, as an adult studying Hutchinson’s story, I understand his response. Among a raft of fascinating ancestors, Anne is most alluring and enigmatic. As a wife, mother, and journalist living in modern Boston—a palimpsest of the settlement where Anne had her rise and fall—I am intrigued by her life and thought. How, in a virtual wilderness, did she (like countless other women) raise a huge family while also (unlike the rest) confronting the privileged men who formed the first colony and educational center of the United States? According to Harvard University, it is she rather than John Harvard who “should be credited with the founding of Harvard College.” In November 1637, just a week after her first trial and banishment, colonial leaders founded Harvard to indoctrinate young male citizens so as to prevent a charismatic radical like Hutchinson from ever again holding sway in Massachusetts, observes the Reverend Peter J. Gomes, the Plummer Professor of Christian Morals at Harvard University.