Read American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett Online

Authors: Buddy Levy

Tags: #Legislators - United States, #Political, #Crockett, #Frontier and Pioneer Life - Tennessee, #Military, #Legislators, #Tex.) - Siege, #Davy, #Alamo (San Antonio, #Pioneers, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Tex.), #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Pioneers - Tennessee, #Historical, #1836, #Soldiers - United States, #General, #Tennessee, #Biography & Autobiography, #Soldiers, #Religious

American Legend: The Real-Life Adventures of David Crockett (29 page)

The humor of the narrative prefigured and no doubt influenced the work of Mark Twain, and set a very high standard for future American humorists, precisely because it appealed to a wide range of readers.

The question of whether Crockett accurately conveyed the history of his life presents a host of vexing considerations. His recollections are uneven and evidently fabricated in a few places, and there is no doubt, given the timing of its release, that the book was politically motivated. As such, it’s a performance of sorts, playing on the desire for tall tales his readership would have expected from him, and giving him an opportunity to justify his very public break with Andrew Jackson. He cleverly avoids much discussion of his time in Congress, likely because it was ineffectual, but also since he seemed to genuinely prefer tales of his boyhood adventures and days afield to what he considered the painfully slow churning of the country’s political wheels.

It’s true that he fudged his involvement in the Creek War mutiny, probably as a way to set forth an early and justifiable animosity toward Jackson; it’s also true that he wrote of some battles in which he never took part, aware that a respected war record reflected well during political campaigns. And while he failed to include such fundamentals as the names of his own wives, siblings, and offspring,

10

he managed to infuse the text with pertinent political satire, so that the book can be read as a thinly veiled campaign circular. But those are minor transgressions given the breadth of what he managed to achieve in writing his

Narrative:

a peerless American voice that stood to represent the desire of a nation. It was, and remains, a remarkable literary achievement.

Crockett hoped that it could right his listing financial ship. During the writing process he corresponded with John Wesley and mentioned that he was considering a tour in the east at recess to help promote the book, convinced that his presence would “make thousands of people buy the book.”

11

The nagging fact of his indebtedness still ate away at him, becoming an element of shame so profound that he could barely face the people he owed, and if things went well, the book might just be his ticket to solvency. “I intend never to go home until I can pay all my debts,” he told John Wesley, “and I think I have a good prospect at present and I will do the best I Can.”

12

At the same time, perhaps fired by the apparent ease with which writing came to him and the potential for profits, he conspired to help produce the first two

Almanacs,

which were essentially reprinted excerpts from his autobiography and contained bear hunting yarns and other amusing anecdotes, and these he mass-marketed, producing on the order of 20,000 to 30,000 copies, many of which he hoped to sell himself along his book tour route.

13

But before he could depart on his book tour, he had to face the tedium of his role as congressman, while preoccupied by the hullabaloo of the book release. The truth was that what little patience he ever possessed for the ennui of congressional proceedings was now completely gone, replaced by the very real excitement of the potentially lucrative book tour, and a feeling of importance, perhaps even superiority, at the attention his book won him. His behavior on the House floor, which had grown progressively more “eccentric” and idiosyncratic over the years, now bordered on erratic and even unstable. Fueled by the controversy over Jackson’s removal of the bank deposits between sessions, Crockett launched into scornful rants, becoming disorderly, breaching the decorum the congressional halls demanded.

His verbal assaults grew hackneyed, for he and others had used many of them before, describing Jackson in hyperbolic epithets like “King Andrew,” and even aligning him with dictators and despots, remarking in a letter to friend William Yeatman:

He [Jackson] has tools and slaves enough in Congress to sustain him in anything that he may wish to effect. I thank God I am not one of them. I do consider him a greater tyrant than Cromwell, Caesar or Bonaparte. I hope his day of glory is near at end! If it were not for the Senate God only knows what would become of the country.

14

Crockett’s public seething managed to get attention, and had the effect of keeping his name in the papers, cementing his reputation in politics as one of Jackson’s most vehement critics. Seeing that any movement on his lame land bill appeared remote, Crockett achieved the nearly inconsequential victory of procuring postal service for diminutive Troy, Tennessee, through Obion County.

15

Other than that, he effectively ignored the business of Congress and, as a result, the desires of his constituency, focusing instead on himself and the business of solidifying his name and image in the popular consciousness.

He was so impatient, so intoxicated with stardom that he did not even wait until the end of session to begin the process. He would leave smack in the middle of the session, despite some earlier criticism about his tendency toward absenteeism. But before he left, there was some socializing to do, and Crockett hooked up with his old pal Sam Houston, who was in Washington after his self-imposed exile among the Cherokee. The two were seen at parties, dinners, and in the company of a woman named Octavia Walton, whom Houston was apparently courting and whose guest book each signed while they visited and shared drinks.

16

Houston was in town on official business, having recently come from Texas, which he likely told Crockett was ripe for the picking. He may have reiterated what he had recently told James Prentiss: “I do think within one year it [Texas] will be a Sovereign State and acting in all things such. Within three years I think it will be separated from the Mexican Confederacy, and will remain so forever.”

17

Houston understood firsthand already what Crockett would later see—that Texas offered the newest frontier of the West, where opportunistic men, in the right place at the right time, might make their fortunes.

As they reminisced about old times and pondered the future, Houston must have described to Crockett the wild and undeveloped hunting grounds and the seemingly endless expanses of land for the taking. Houston was utterly intoxicated with Texas, his unbridled enthusiasm evident in a note to his cousin some months before: “Texas is the finest portion of the Globe that has ever blessed my vision.”

18

The prospects in Texas would have piqued Crockett’s interest considerably. They parted ways, perhaps with plans to meet again in Texas.

Plagued as he had been over the years by relapses of malaria, Crockett could sometimes use his health as a fairly legitimate excuse for his tendency to be a congressional truant, and when he was later criticized for packing up and going on a “Towar Through the Eastern States,” he would play the health card once again. But he fooled no one. There were other factors at work as he departed Washington on April 25, 1834, later ensconcing himself in Baltimore’s Barnum’s Hotel and preparing for a lovely meal with Whig cronies to discuss his upcoming tour. He had already intimated to John Wesley that he intended to advance book sales through public appearances, and on April 10 he wrote a letter to Carey and Hart requesting 500 copies of the book that he could take along and peddle on his own.

19

His Whig friends and political supporters had arranged an elaborate speaking tour and public appearance itinerary for him, and the shrewd, innovative, and media-savvy David Crockett figured to hawk as many books along the way as he possibly could, creating what was the first ever official “book tour.”

20

It was at once a stroke of marketing genius and political suicide.

GETTING OUT OF WASHINGTON would have been a great relief to Crockett, and the trip was one of the most delightful and electrifying he ever made, as he was paraded, wined, dined, and fêted through the most vital cities along the eastern seaboard, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. It was a highly structured and tightly monitored publicity tour orchestrated by the Whigs, who were trotting Crockett out to see how he played, the better to determine whether the obstinate and headstrong frontiersman-cum-congressman and a noted loose cannon might prove malleable enough to make presidential material two years hence. Massive crowds turned out at every stop along the way, all hoping to get a glimpse of the American original, all hoping to hear him utter some outlandish anecdote. For the most part, he did not disappoint, though he was also expected by the Whigs to come out in defiance of Jackson and Van Buren, pacifying partisan crowds with practiced rhetoric, including the old contention that “I am still a Jackson man, but General Jackson is not.”

In Baltimore, he gave a speech in the affluent community of Mt. Ver-non Place beneath a statue of George Washington.

21

He then boarded the steamship

Carroll-of-Carrolton,

which bore him across the Chesapeake, then went by train to Delaware City, and “re-embarked there for a trip up the Delaware River, and arrived in Philadelphia that evening, April 26.”

22

The tour was well conceived, with adoring, cheering throngs greeting him at every stop along the way.

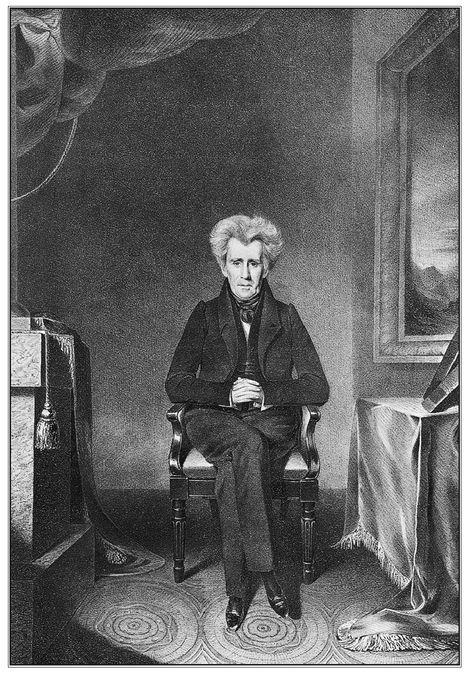

President Andrew Jackson, Crockett’s archnemesis. Of their political rift Crockett would claim, “I am still a Jackson man, but General Jackson is not.” (Andrew Jackson. Portrait by Albert Newsam, copy after William James Hubard. Lithograph, print 1830. Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.)

In Philadelphia, Crockett made a brief speech and was then paraded to a hotel directly across the street from the United States Bank, certainly no mere coincidence. In the next few days he was whisked about the city, touring the civic waterworks, the asylum, the Navy Yard, the stockyard, the mint, and the exchange, where as requested he launched into his patented anti-Jackson oratory.

23

Prominent young Whigs of Philadelphia presented the beaming Crockett with a watch, chain, and seal bearing his now-famous motto, “Go Ahead,” and offered him the present of a new rifle, to be delivered upon completion to his personal expert specifications. It was the perfect gift for a man whose reputation had been made in part by his skills with the long rifle, in target and sport as well as in the pursuit of wild game.

On April 29, Crockett left Philadelphia for New York, sailing (for the first time) up the Delaware on the

New Philadelphia,

then boarding a train and crossing northern New Jersey to Perth Amboy, where he changed trains to New York City.

24

The pace and schedule in New York were just as frenzied as in Philadelphia, but this fit with Crockett’s solidifying persona of politician, celebrated personality, and author. Crockett’s predictions and projections about his tour, and the effect it would have on his book sales, were fairly astute and accurate. While in Philadelphia, he had briefly met his publishers and coordinated a print run of 2,000 copies of his

Narrative,

to which they agreed. Sales were booming.

25

On arrival in New York, Crockett was met by a knot of young Whigs who boarded the train and treated him like the dignitary he was, shepherding him to his opulent lodgings at the American Hotel, where he would remain comfortably, but breakneck busy, for nearly a week. On his first night in New York he took in a burlesque show, complete with slap-stick sketches, dancing, and ribald comedy. The next day, moderately rested, Crockett rose and was brought to the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street, where he delivered a prearranged speech. The highlight of the day came when he took lunch with Seba Smith, the creator and author of Major Jack Downing. The two men must have shared some amusing banter, agreeing that their literary alter egos would exchange letters in the

Downing Gazette

.

26

Later in the afternoon he visited Peale’s Museum of Curiosities and Freaks, where he witnessed scientific specimens the likes of which he had never encountered, and watched a ventriloquist, which dazzled and amazed him. The ventriloquist was also a magician, and he performed a few tricks, including making money disappear and magically reappear. Crockett used the moment to master his own comic timing, as he quipped jokingly, “He can remove the deposits better than Old Hickory.” The assemblage erupted with hoots, laughter, and applause.

27