American Lightning: Terror, Mystery, the Birth of Hollywood, and the Crime of the Century (20 page)

Authors: Howard Blum

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism

“Yes, perfectly. I will leave tonight.”

“All right. Good-bye,” Billy said, and then hung up the phone.

The next day the tail he had put on Emma McManigal reported that she had gone to Indianapolis and met with J.J. McNamara. Billy congratulated himself. Maybe he really should have been an actor. His performance had convinced Emma McManigal. Now all he could do was hope J.J. McNamara had been persuaded, too.

As Billy continued to wait, and as his men continued their uneventful surveillance of the union leader, Los Angeles assistant district attorney Robert Ford arrived in Chicago. He worked swiftly to present the requisition papers to the Illinois authorities. A secret extradition was approved. Billy instructed the men guarding McManigal and Jim McNamara that as soon as he sent word, they should drive the prisoners to Joliet and board the fast train to Los Angeles. Then he went off to Indianapolis to make an arrest.

A light, early spring rain was falling on April 22, 1911, when Billy, accompanied by two local police detectives, went to the Structural Iron Workers offices. An officer rapped at the door. Billy deferentially stood to the side; it was his case,

his

moment of triumph, but he knew he had no legal authority.

A pleasant-looking man with a shock of gray hair that seemed out of place with his youthful face opened the door.

“I want to see J.J. McNamara,” the officer announced.

“I’m the man,” said McNamara. If he had any suspicion of the reason for the police’s arrival, he did not show it.

“Well,” said the officer, “the chief would like to see you.”

Suddenly J.J. understood, and a rush of panic hit him. Moments before J.J. had been sitting at a long walnut conference table with Frank Ryan, the union’s president, and six other members of the executive committee. J.J. now went back to the room and huddled anxiously with Ryan. “They’re after me. What had I better do about it?” he whispered.

“You’d better go ahead,” Ryan advised.

J.J. considered, then realized he had no choice. “I’ll get my hat,” he said. But he also made sure to close the union’s safe. Trying to regain a bit of his usual breezy manner, he told the executive committee members as he was being led out the door, “I’ll be back in time to make the motion for adjournment.”

Billy hadn’t said a word during the entire arrest. It wasn’t necessary. He knew his moment would come. And he knew that if things worked out as he had planned, J.J. McNamara would not be back in the union office, or even in Indianapolis, for a long, long time.

TWENTY-EIGHT

______________________

A

T LAST, TWO

very long days later, Billy boarded the

California Limited.

The

Limited

was a wonder, not just the fastest way from the Midwest to the coast but also the most luxurious. The dining car was first-rate, and there was even an onboard barber, a beautician, a steam-operated clothing press, and a shower-bath. And in separate cars, guarded by Winchester-toting police officers, Billy had sequestered the McNamara brothers and McManigal.

The detective was both exhilarated and totally drained. The past days had been a whirlwind. They were filled with moments that were too large, too consequential, to be understood as they happened. But now sitting in a comfortable tufted-red-leather window seat, the countryside outside swiftly changing like successive scenes in a movie, Billy could begin to review the events that had followed the arrest of J.J. McNamara.

Less than an hour after being led from his office, J.J. stood before police court Judge James A. Collins. In a deep booming bass—a voice from Olympus, Billy approvingly decided—Judge Collins had read the extradition papers. Signed by the honorable governors of the states of Illinois and California, John J. McNamara was to be sent to Los Angeles to stand trial for the dynamiting of the

Times

Building and the Llewellyn Iron Works. He was also charged with twenty-one murders.

J.J. paled. Billy watched as the union leader leaned on a chair to steady himself. At that moment the detective tried to feel sympathy, but he could not.

Pointing a long accusatory finger at the union leader, the judge asked, “Are you the man named in the warrant?”

It took J.J. a moment to find the words. Finally: “I admit that I’m the man named in the warrant.”

“Very well, then,” said the judge, “the only thing left for me to do is to turn you over to the State of California.”

Recovering some of his former confidence, J.J. began to protest. “Judge,” he insisted, “I do not see how a man can be jerked up from his business when he is committing no wrong and ordered out of the state on five minutes’ notice. Are you going to let them take me without giving me a chance to defend myself? I have no attorney and no one to defend me.”

The judge cut him off. The man accused of the crime of the century had no rights in his court.

“Take him away,” the judge ordered.

Handcuffed to a police officer and accompanied by Billy’s handpicked Chicago police detective, Guy Biddinger, McNamara was led to a waiting seven-passenger Owen motorcar. The officers were armed with rifles and large-caliber revolvers. Two hundred rounds of ammunition were stored by the front passenger seat. Billy instructed Frank Fox, the driver, to go as fast as possible. Don’t stop for anything, he warned. No matter what McNamara’s friends try, keep going. Billy had a plan, and for it to work they needed to be in Terre Haute, Indiana, not a minute later than 1:45 that morning.

But it was now 6:45

P.M.

, and Billy’s long night was only starting.

Billy returned to the union headquarters in downtown Indianapolis. He was accompanied by an entourage of police, city officials, and reporters. Now that the press had been brought in and the arrests had been announced, Billy made sure it was his show. An instinctive performer, Billy played both to the occasion and to the crowd.

Like a king claiming his throne, Billy sat down in the big ladderback chair in front of McNamara’s roll-top desk.With deliberately elaborate attention, he began examining the union leader’s papers. All the while the reporters made note of his every gesture.

“Who are you,” Frank Ryan, the outraged union president, demanded, “that you have a right to come in these offices and search these apartments?”

“Burns,” the detective answered, full of his own importance and authority. It was only a single one-syllable word, yet he was certain it would carry all the explanation that was necessary.

The room went quiet. Ryan stared at his adversary. Reporters watched, documenting in their notebooks the intensity charging through this small moment of confrontation. “Ah, and who is

Burns

?” Ryan asked disingenuously.

Billy rose from the desk. Insulted and demeaned, it was as if all the frustrations in the long course of his investigation had risen up at once within him. He was looking for a fight.

Ryan did not back down. The union president, a steelworker for years, had traveled his own hard road. He moved toward the detective.

All at once Police Superintendent Hyland stepped between the two men. His bulky presence was an effective obstacle, and the moment passed.

Now ignoring Ryan, Billy headed toward the union’s safe. He had found a set of keys on McNamara’s desk, but he tried each one only to discover that none of them worked. The safe would have to be drilled. Billy asked the chief of police to get a locksmith. In the meantime, Billy would move on. Like a tour guide, he announced that anyone who wanted to join him was welcome.

It was nearly midnight by the time Billy and his eager troops arrived at the barn on the outskirts of Indianapolis, near Big Eagle Creek. A day’s rain had turned the approach to the barn into a sea of mud. Beams from flashlights and torches struggled to light the way through the nearly starless night, and each new step across the oozing, sloshing field was a small battle. In his confession, Ortie McManigal had revealed that a cache of “soup” was hidden in a locked piano box in the barn. Once the box was found, Billy reached into his pockets and took out a set of keys he had confiscated from Jim McNamara. He kept trying keys, until finally one opened the box.

Inside was another locked box. Billy had not expected this. For a moment he seemed to falter. What if McManigal had been lying? Determined not to betray his doubts, he began trying McNamara’s keys on the new lock. At last one worked. He had to reach deep into a packing of sawdust until, with a magician’s sense of drama, he extracted two quart cans of nitroglycerin and, relishing the moment, fifteen sticks of dynamite.

Billy made sure that each of the reporters had a good look at his discoveries.

An hour and a half later on that same endless night, Billy was back in the downtown union office. The locksmith had still not arrived, but now a janitor approached the famous detective. He, too, wanted to play a role in breaking this momentous case. “Mr. Burns,” he suggested, “do you want to search the vault in the cellar?” Billy had not previously known about the vault, but now he hurried to the basement. Full of curiosity, his entourage followed.

Billy inspected the vault and decided that the doors would have to be wrenched off. He instructed the officers to get crowbars and begin. But before the work could start, Leo Rappaport, the union’s attorney, arrived. He demanded the officers desist. The court’s warrant granted the authorities the right to search only the fifth-floor offices, not the cellar.

Billy’s instinct was to ignore the attorney. He’d do what needed to be done, and damn the law. But as he was about to give the officers the order to proceed, he stopped himself. Everything that occurred tonight would have to stand up to a judge’s—a nation’s!—scrutiny. Get Mr. Rappaport his warrant, he told the police superintendent.

By 1910, Los Angeles had become “the bloodiest arena in the Western world for capital and labor.” The editorials in the fiercely anti-union

Los Angeles Times

gleefully fueled the tensions.

Courtesy Brown Brothers USA

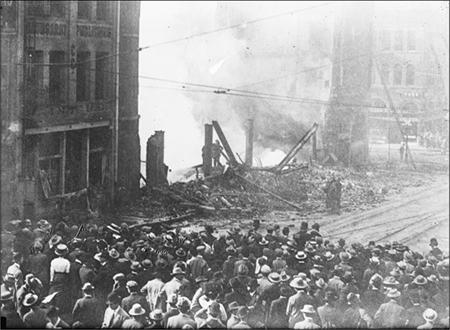

“The crime of the century”: After midnight on October 1, 1910, a series of explosions thundered through the

Los Angeles Times

Building and left twenty-one dead.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ggbain-08499

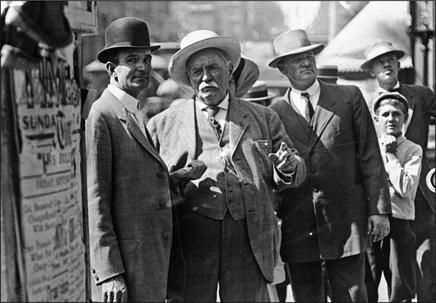

Gen. Harrison Gray Otis, the owner of the

Times,

inspects the ruins of his news-paper’s headquarters. “Depraved, corrupt, crooked, and putrescent” was how one labor supporter publicly described Otis.

Los Angeles Times Company Records, The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

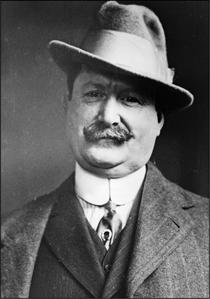

Billy Burns, “the American Sherlock Holmes.” “The only detective of genius whom the country has produced,” gushed a

New York Times

editorial.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-101093