American Rose: A Nation Laid Bare: The Life and Times of Gypsy Rose Lee

Read American Rose: A Nation Laid Bare: The Life and Times of Gypsy Rose Lee Online

Authors: Karen Abbott

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Women

ALSO BY KAREN ABBOTT

Sin in the Second City

Copyright © 2010 by Karen Abbott

All rights reserved.

Jacket design: Lynn Buckley

Jacket images: Getty Images (Gypsy Rose Lee), Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images (Times Square), Jessica Hische (hand-lettering)

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R

ANDOM

H

OUSE

and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Alfred Publishing Co., Inc., and Imagem Music for permission to reprint “Zip” from

Pal Joey

, words by Lorenz Hart and music by Richard Rodgers, copyright © 1951, 1962 (copyrights renewed) Chappell & Co., Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Alfred Publishing Co., Inc., and Imagem Music.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Abbott, Karen.

American rose : a nation laid bare : the life and times of Gypsy Rose Lee / by Karen Abbott.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60456-3

1. Lee, Gypsy Rose, 1911–1970. 2. Stripteasers—United States—Biography. 3. Authors, American—20th century—Biography. I. Title.

PN2287.L29A63 2011

792.702’8092—dc22

[B]

——————

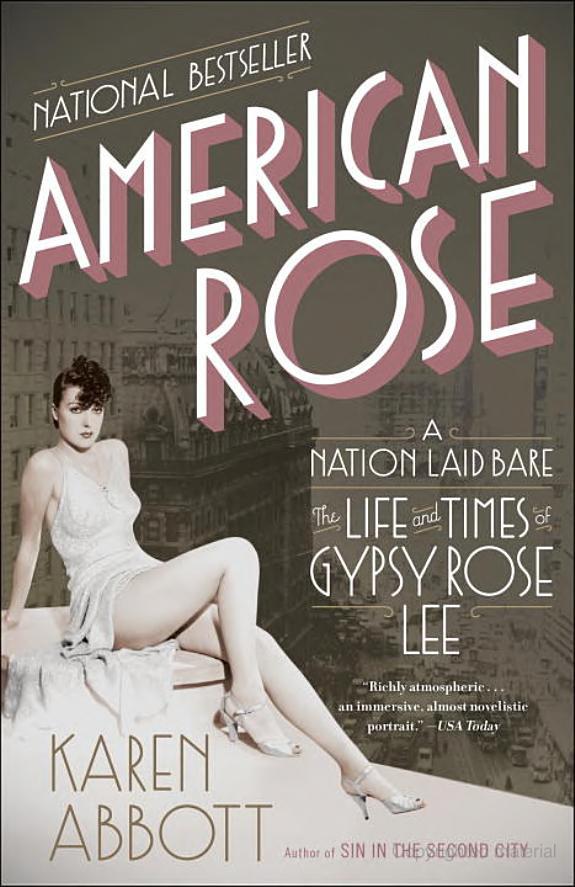

FRONTISPIECE

:

Rose Louise Hovick posing as “Hard-boiled Rose.”

v3.1_r1

For my grandmother

,

Anne Margaret Scarborough,

another indomitable lady of the Depression

Genius is not a gift, but the way a person invents in desperate circumstances.

—Jean-Paul Sartre

May your bare ass always be shining.

—Eleanor Roosevelt to Gypsy Rose Lee, 1959

My interest in Gypsy Rose Lee stemmed not from the movie or play based on (part of) her life but from television—reality television in particular—a medium and genre that didn’t even exist when a girl named Rose Louise first talk-sang lyrics on a stage. In our current cultural norm, where the route to fast (if fleeting) fame is to package and peddle moments once considered in the private domain, there is something compelling about a woman who achieved lasting, worldwide renown without letting a single person truly know her. The “most private public figure of her time,” as one friend eulogized Gypsy, sold everything—sex, comedy, illusion—but she never once sold herself. She didn’t have to; she commanded every eye in the room precisely because she offered so little to see.

Trying to discover Gypsy the person, as opposed to Gypsy the persona, became the sort of detective story she herself could have written. Her memoir contains nuggets of truth—the rotating collection of pets, the struggles during the Depression, the family’s wary views of men—but these were tempered throughout by invention and fantasy, whatever Gypsy decided would best benefit the character she’d so meticulously created. It was fitting that

Gypsy

the musical—a production Frank Rich of

The New York Times

called “Broadway’s own brassy, unlikely answer to ‘King Lear’ ”—was and is billed as a “fable”: Gypsy

had always preferred stories that favored ambiguity over clarity, humor over revelation.

I spent many hours thoroughly engrossed in Gypsy’s archives at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, and after a while even the most prosaic bits of information (or lack thereof) became suspect: Were the New Year’s goals listed in her diary (“Speak well of all or not at all,” “I will try to live each day as tho I’m meeting god that night,” “To be right too soon is to be in the wrong”) written honestly in the moment, or with an eye toward posterity? Wasn’t it odd that she spent a month detailing her mother’s hospice care, yet recorded her death in four succinct words? (“Mother died at 6:30.”) Wasn’t it odder still that she was similarly terse in noting the death of Michael Todd, the one great love of her life? (“Mike was killed in a plane [crash] at 4:30.”) And how could an iconic sex symbol write a memoir without once mentioning her own sex life?

So I read and reread and fact-checked everything I could, tasks that helped me clarify supporting characters and timelines but did little to unravel the layers of Gypsy’s mystique. To that end, I was incredibly fortunate to connect with the two persons who knew Gypsy best: her only son and her only sister. The relationship a woman has with her child vastly differs, of course, from the one she has with a sibling, and the intensely personal anecdotes and insights Erik Preminger and June Havoc were kind enough to share went a long way toward revealing parts of Gypsy I would otherwise never have seen. From Erik, I gathered that his mother was an array of complexities and contradictions: a “madly self-assured” woman who hid her nerves and insecurities; an avid student of Freud who disdained introspection; a “fairly sad person” and “wounded soul” despite a desperate need to “keep her heart close”; an authority figure capable of inspiring awe and exasperation and loyalty and fury and love, often within the very same moment.

June’s memories are darker and more melancholy, which I attributed partly to the fact that she’d expected to die relatively young, just like her mother and sister before her. It is hard to fathom that the brave, brilliant girl she knew as Louise has been gone, now, for forty years—nearly half of June’s remarkably long and wonderfully rich life. I first met June in March 2008, exactly two years before she passed away, hoping she

would guide me through Gypsy’s mythology, peeling away the punch lines and fanciful digressions to reveal a core of truth.

When I arrived at June’s Connecticut farm I found her lying in bed, her hair done up in pert white pigtails, a snack of Oreos and milk arranged on a side table. Her eyes were a bold shade of blue and painfully sensitive to light; she couldn’t go more than a few moments without moaning and clenching them shut. She was ninety-four years old, give or take (her mother, the infamous “Madam Rose,” was a prolific forger of birth certificates), and the legs that once danced on stages across the country were now motionless, two nearly imperceptible bumps tucked beneath crisp white sheets. She painted a deceptively frail picture, I learned soon enough; this wisp of a woman had retained her survivor’s grit, her cannonball voice, her savvy instinct to question any stranger prying so deeply into the past. A part of me believed, all physical evidence to the contrary, that, if so inclined, she could leap up and strangle me with quick and graceful hands.

But she was welcoming and funny (lamenting a life steeped in “rumorsville”), and genuinely appreciative of my gift—a video of her four-year-old self performing in a 1918 silent film. She gave canned answers to certain queries—answers I’d heard or read elsewhere that nevertheless seemed illuminating when delivered face-to-face, by that deep and resonant voice. If her sister had shown any talent at all, she, June, would never have been born. Her vaudeville audience was like a “big, warm bath,” and the closest thing she had to family. Her mother was by turns tender and pathetic and terrifying, broken in a way that no one, in that time or place, had any idea how to fix. The musical

Gypsy

distorted her childhood so thoroughly it was as if “I didn’t own me anymore.” The tone of her fan mail changed overnight, from sentiments of “loving affection” to “what a little brat you must have been.” June realized her sister was “screwing me out in public,” and that, in the end, there was no stopping either

Gypsy

or Gypsy; the play was both her sister’s monument and her best chance for monumental revisionism.