"No," she said quickly. "Don't touch that."

|

I drew back and apologized.

|

"It's okay," she said. "But you aren't initiated." She looked around for Alagba, and scolded him for not acting as quickly as had "a stranger.'' I exchanged a glance of sympathy with him, but there wasn't much I could do on his behalf.

|

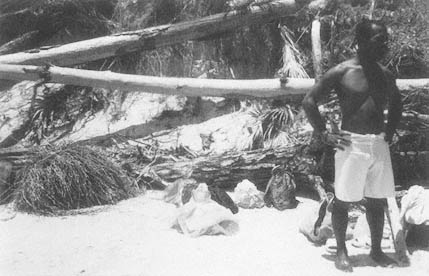

We walked the boardwalk to the sandy white beach beyond the fringe of trees, some torn down by a recent hurricane. The tide was coming in and the area was filled with sunbathers. We didn't look like them. Iya Ghandi, clad in white blouse, loose white pantaloons and head scarfas were Chief Alagba and Iya Shangoarranged the pots on the sand and waded into the sea, shaking a castanet and singing a Yoruba praise hymn.

|

Chief Alagba began taping. The children sat near the pots, watching. Iya Ghandi came back from the sea, barefoot and wet from the knees down. She knelt, took her obi from a bag and cast them on the sand. She said it was a good reading and smiled. At that moment, a pair of Marine jets boomed in from over the horizon and headed out over the Atlantic.

|

Ghandi and Alagba then carried each of the tureens into the waves, where they emptied the old water and replaced it with new. When they'd finished, they covered each of the pots again, said a prayer, and the ceremony was concluded.

|

The kids were in the water in a flash. Lacking a change of clothes, I hung back on the beach, but it was so hot I at least peeled off my shirt, the better to blister.

|

Alagba waved, and I turned to see Chief Elesin trooping down the boardwalk in black mesh tank top and shorts like a San Diego surfer, ice chest under arm and radio tuned to a funk station. As soon as he reached the sand he peeled off his clothes down to a leopard-pattern bikini brief. On his lean, muscled body, it looked good. He sprinted toward the water, then stopped abruptly, as if he'd forgotten something. He ran back toward the pots and fell forward on his hands, in what resembled a modi-

|

|