America's Nazi Secret: An Insider's History (13 page)

Unmarked South River Grave of Emaunuel Jasiuk.

Unmarked South River Grave of Emaunuel Jasiuk.

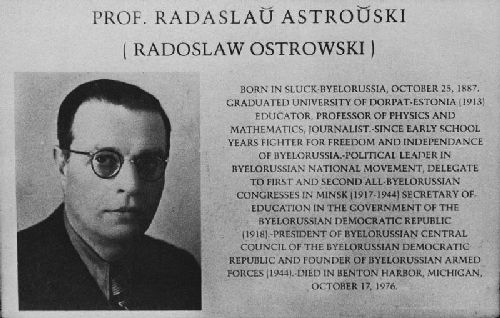

Photograph and biography of Radoslaw Ostrowski on his gravestone in South River, NJ. (Washington Post photographs by Bill Snead).

Photograph and biography of Radoslaw Ostrowski on his gravestone in South River, NJ. (Washington Post photographs by Bill Snead).

Prologue

Rain and darkness blurred the landscape as we turned off the New Jersey Turnpike at Exit 9 one night at the end of October 1980. As the windshield wipers flicked back and forth, the driver hesitated at the bottom of the exit ramp to examine the road signs. New Brunswick, the home of Rutgers University, lay to the left, but the driver turned right toward South River. Within a few minutes we passed through the outskirts of the town, headlights throwing shadows on the walls of dark warehouses and shopping centers. Then we were in the gritty downtown where the neon beer signs in the tavern windows created little islands of light in the empty night.

While the driver kept his eyes on the road, the three passengers concentrated on a carefully marked map, checking it against a list of names and addresses. I was a federal prosecutor attached to the Office of Special Investigations, the Nazi war crimes unit of the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice; my companions were a State Department security man, a New Jersey state trooper in civilian clothes, and an informant who had put us on the long-hidden trail of the Belarus SS Brigade and the Nazi puppet government of Byelorussia.

For myself, this trip was the culmination of eighteen months of work. Shortly after joining the Justice Department as a member of the Attorney General’s honors program, I had seen a notice on an office bulletin board asking for volunteers for the Office of Special Investigations. In May 1979, I applied and was accepted.

My first assignment was to help build cases against several Byelorussians who had been admitted to the United States and allowed to become citizens, despite strong evidence that they were guilty of war crimes. The assignment was not made any easier by my having – as do, I suspect, most Americans – only a passing knowledge of Byelorussia and its tortured history.

I learned that Byelorussia, sometimes called White Russia, had become a post-war Soviet Socialist Republic with a population of some eight million. It borders on Poland in the West, Lithuania and Latvia in the northwest, Russia in the east, and the Ukraine in the south. During World War 11, Byelorussia was occupied by the Germans from 1941 to 1944, and was one of the most devastated regions of the Soviet Union. Some of its citizens served the Nazi puppet government and some even served in an SS unit known as the Belarus Brigade which fought against the Americans. It was these ex-Nazis, now thought to be living in the United States, who were the object of our inquiry.

OSI’s task was a difficult one, because we were dealing with events that had occurred nearly forty years before in a foreign country. And not only did the Soviet Union sometimes refuse to provide witnesses to crimes committed within its borders but American intelligence agencies as well seemed curiously reluctant to cooperate with us. Time after time, I had been told that no one knew where the old files were stored, or even where an index could be located. I spent weeks in underground vaults, learning the intricacies of long-forgotten intelligence operations, and then systematically retrieving the records from their dusty containers. It took years to reassemble all the documents, many of which had never even been translated. But there was one document that I could not forget: the memoir of Solomon Schiadow, who had survived the Byelorussian holocaust. Whenever I felt frustrated by a dead end or an uncooperative agency, I would remember what he had written, and feel renewed determination to keep on, sifting through the files for traces of the men who had committed the atrocities he recorded.

Eventually, some of the pieces of the puzzle started to come together in South River. OSI had learned that several Byelorussian Nazi collaborators lived there – little more than a three-hour drive from the nation’s capital – but an informant had discovered that their numbers were actually much larger than OSI’s estimate. So as not to arouse suspicion, we came on this night to check out the facts of this curious situation.

South River sprawls along the meandering stream for which it is named like a bent and wrinkled arm. Sometimes the damp wind sweeping down from the northeast carries with it the smell of the refineries and petrochemical plants of Carteret and Bayonne that lie just over the horizon. Founded in colonial times, South River has become an enclave of Eastern European immigrants. Russians, Byelorussians, Ukrainians, Hungarians, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, and European Jews have all found a haven there. As the members of each ethnic group have prospered, they have moved away from the river, up to neat bungalows that line the nearby hills. Perhaps the town’s most famous citizen is Joe Theismann, former star quarterback for the Washington Redskins.

Shortly after midnight we pulled up in front of St. Euphrosynia’s Church on Whitehead Avenue.

[1]

Despite the darkness, a tall monument on a mound behind the church was clearly visible. GLORY TO THOSE WHO FOUGHT FOR THE FREEDOM AND INDEPENDENCE OF BYELORUSSIA read the inscription on the base. Atop the stone pillar, flanked by a white-red-white Byelorussian flag and the Stars and Stripes, was a circle of iron enclosing a double-barred cross. This was the same symbol that the Belarus SS unit had worn as it went into battle against American troops toward the end of World War II.

We drove past the onion-domed churches of Russian Alley and up a hill lined by large graveyards. Off to one side, as if holding itself aloof, was another, much smaller cemetery. The iron-barred gate was padlocked, but a plaque to the left identified it as the “White Ruthenian (Byelorussian) Orthodox Cemetery of St. Euphrosynia in South River.” A plaque on the right bore a verse from the Twenty-third Psalm: “I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” I climbed over the low wall while the others kept watch, and in the dim light saw that the plot was only about one-third full. It was too dark to make out the names carved on the tombstones in Cyrillic lettering, so we decided to return when the light was better.

Early the next morning, I went over the wall again. Moving quickly up and down the rows of graves, many of which appeared new, I read the names onto a tape recorder that I had brought with me so we could check them off later against our list of fugitive war criminals. In the center of the cemetery, occupying the most prominent place, I found a tall gray stone. It marked the grave of Radoslaw Ostrowsky. The framed photograph affixed to it in accordance with Russian Orthodox custom showed an ascetic, lean-faced man with a look of righteous intensity. A plaque identified Ostrowsky as the “President of the Byelorussian Central Council” during World War II and the founder of the “Byelorussian National Armed Forces.” We had found the final resting place of one of the highest-ranking war criminals ever to become a United States citizen, as far as is known.

Surrounding Ostrowsky’s grave were the graves of his fellow war criminals: mayors, governors, and other officials. These were men who had ruled the Nazi puppet state of Byelorussia; who had guided the SS Einsarzgruppen, the mobile killing squads, across a good part of Eastern Europe; who had assisted in the mass murder of thousands of Jews; whose atrocities had even sickened some of their German masters.

Suddenly, the gate creaked behind me. I stuffed the tape recorder under my coat and turned to see my companions frantically signaling me to jump over the wall. A tall man in a leather jacket was working a key in the lock of the cemetery gates. He had a narrow face and cold, deep-set eyes that seemed disturbingly familiar.

It was too late to run, so I decided to act as if I had a right to be there. I walked over to the stranger and asked if he could help me find the grave of Emanuel Jasiuk. Obviously surprised, he asked in strongly accented English for my connection with Jasiuk.

My father had met Jasiuk after World War II, I explained, and he had requested me to visit his grave if I ever came to New Jersey.

How did your father know Jasiuk, the tall man inquired.

He had been attached to an Air Force Intelligence unit that had been stationed near Stuttgart in West Germany, I said. The man nodded and led me to a recent grave near the rear of the cemetery.

All the other graves had headstones with ornate carvings and photographs in brass frames, but the plot of Emanuel Jasiuk was marked by only a bed of flowers and a simple white cross.

Under the approving gaze of the watchman, I stood over the grave for a few moments with my head bowed. To make a graceful exit, I asked for directions to a florist so I could return with a wreath as a remembrance from my father. With a smile, he furnished directions to a nearby flower shop as he escorted me to the gate, where my companions awaited me.

“You can come by any morning,” he said, struggling for the words in English. “I’m sorry it couldn’t have been a more joyful occasion.”

As soon as our car pulled away, my companions burst out laughing. Somewhat irritated, I demanded to know what was so funny about my narrow escape, and they told me that the watchman I had just talked to was one of the fugitives we were seeking. He had become the parish priest.

And then I remembered the Justice Department file where I had first seen his photograph. He had been a county chief in Byelorussia, and had commanded police forces that had murdered thousands of his own countrymen, Poles, and Jews. How could such a man be living peacefully as an American citizen in a New Jersey town, I wondered with frustration, incredulity, and outrage. These were feelings I was to experience countless times as I went about tracing the origins of the long-suppressed “Belarus Secret.

[

1

] Inside the church is a commemorative plaque listing the members of the building committee. Many of those named were prominent collaborators during the Nazi occupation.

Frank Wisner

Frank Wisner

1

Frank G. Wisner did not look like a spymaster.

Balding and fleshy although he was not yet forty, he appeared to those who greeted him upon his arrival in West Germany in the summer of 1948 like the prosperous Wall Street lawyer he had been. He spoke with a trace of the soft accent of his native Mississippi, and his official title, Director of the Office of Policy Coordination, was innocuous. He had chosen it himself for that reason. Wisner was a veteran practitioner of the black art of covert operations, and the newly organized OPC was in the front line of the secret war against the Soviet Union.

Wisner came to Germany at a time when Europe seemed on the brink of revolutionary upheaval. Berlin was under blockade by the Soviets and depended upon a tenuous airlift for its survival. The Communists were actively trying to overthrow the governments of Greece and Turkey. Italy was on the verge of going communist. A Russian attempt to pinch off a piece of northern Iran had just been repulsed. Half of Europe had disappeared behind the Iron Curtain. To meet the challenge of Soviet expansion, President Harry S. Truman had made substantial amounts of military and economic assistance available to nations facing internal and external communist threats. “Our policy [is] to support the cause of freedom wherever it is threatened,” he declared.