America's Nazi Secret: An Insider's History (21 page)

As soon as Abramtchik reestablished the BNR in Paris in 1946 he went to work usurping Ostrowsky’s position with the British secret service. By the middle of the year, émigré newspapers were reporting that the BNR was being funded by a combination of anticommunist groups, including the Vatican and the London-based Polish government-in-exile. Far from being a front for funding from the British secret service, as the Soviets have suggested, the London Poles were desperately maneuvering on their own to regain control of a country that was rapidly falling under Communist influence. One of their methods was to finance groups that held themselves out as possible sources of resistance to Communist control. The Vatican supplied support to Abramtchik’s group because many members were Catholics from the former Polish provinces of Byelorussia.

70

A special school was established in the Vatican to encourage their postwar nationalism. The curriculum eventually included parachute training, and there is an apocryphal story about a headline in the Vatican newspaper reading “They Fall from the Skies like Angels.”

Bitter infighting erupted among the various Byelorussian factions as they struggled against each other for recognition and financial aid from Western intelligence agencies. They were like salesmen competing for a lucrative account. Ostrowsky’s Orthodox supporters were opposed to Abramtchik‘s links to the Vatican; Abramtchik told the British and French that their opponents, loyal to the Moscow patriarchy, were secretly manipulated by the “Communist” Orthodox Church. Abramtchik soon hit upon a more effective technique: quietly, the word was spread that many of Ostrowsky’s followers were war criminals. In order to avoid public scandals, both the British and French cut their links to Ostrowsky and adopted the “moderate” Abramtchik faction as their channel for dealing with the Byelorussians.

[3]

Ostrowsky appeared to have been left out in the cold, but it was not long before he found new sponsors – Reinhard Gehlen and the Americans.

Along with the cream of Nazi rocket scientists and engineers, Gehlen was one of the prize catches of American military intelligence.

71

As head of FHO, he had amassed a huge amount of information about the Soviet Union.

[4]

Even after the Germans were driven from Russia, Gehlen coordinated the processing of intelligence from the Nazi spy network that had remained behind Soviet lines. Realizing at the war’s end that he would be sought by the Russians for punishment even though he claimed never to have been a Nazi, he made plans to ensure his survival by placing with the Allies his vast storehouse of information on the Soviet Union. Like many other Germans, he was convinced that it was only a matter of time before the alliance between the Russians and the West would collapse. In anticipation of that day, Gehlen microfilmed his entire Soviet intelligence file, stored the microfilm in steel boxes – some fifty in all – and buried them in the Bavarian Alps in the path of the advancing Americans, to whom he and his staff surrendered in May 1945.

Once Gehlen’s identity was established, General Edwin L. Sibert, the Twelfth Army Group’s chief of intelligence, consulted with Allen Dulles, then OSS station chief in Germany. Unlike many generals who distrusted the civilian intelligence service, Sibert respected Dulles’s judgment. Both men agreed that Gehlen would be a prize beyond measure. Through him, American intelligence would obtain an unprecedented opportunity to develop an anticommunist network in Soviet territory. Fearing that the Russians, who were searching for Gehlen to settle old scores, might get wind of the fact that he was in American hands, the military decided to send him to Washington for extended interrogation.

Much to Gehlen’s amusement, the Americans gave him the uniform of an American general to wear as he was spirited aboard a plane in an attempt to avert the attention of Soviet agents. Upon his arrival in America on August 22, 1945, he was put in civilian clothes and installed as an honored prisoner in the interrogation center at Fort Hunt, just across the Potomac from Washington, where Nazi VIP’s, such as Gustav Hilger, were interviewed. There, Gehlen received a steady stream of visitors from the faction-ridden American intelligence community, each of whom had his own ideas how this windfall should best be used. From their conversations and from the Washington newspapers he was permitted to read, Gehlen discovered that his interrogation coincided with an intense struggle among U.S. intelligence agencies for control of future operations. Rather than being a supplicant, he now found himself the center of a bureaucratic tug-of-war.

The American intelligence system was almost as complex as the Nazi apparatus, and the infighting among its members was equally Byzantine. Until World War II, the United States had no centralized intelligence agency. There were the Army’s G-2, the Navy’s ONI, the State Department’s small “research bureau,” and the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s activities in domestic counterespionage. The devastating Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor spot-lighted the lack of cooperation among these agencies and the vital need for coordination. President Roosevelt authorized the creation of the Office of Strategic Services to meet this need and appointed Colonel William J. Donovan, a World War I hero and an old classmate from Columbia Law School, as its head.

72

“Wild Bill” Donovan shaped the OSS in his own image. Flamboyant and daring, he recruited agents from among Wall Street law firms, Ivy League schools, and big corporations. The old-line military intelligence agencies, contemptuous of the new organization, claimed its initials stood for “Oh So Social.” Nevertheless, after a shaky start, the OSS achieved a credible record in the secret war against the Nazis and the Japanese. Impressed with the success of the OSS, Roosevelt planned, as the war neared its end, to create a permanent, centralized intelligence organization with Donovan’s agency as its nucleus. But he had failed to reckon with J. Edgar Hoover, the longtime chief of the FBI.

[5]

Hoover believed that he, rather than Donovan, should head such an intelligence apparatus. A plan prepared by Donovan for the President’s consideration was leaked to the rabidly anti-Roosevelt Chicago Tribune, which warned that FDR was trying to create an “American Gestapo.” Following Roosevelt’s death, the generals and admirals who had also resented Donovan’s power persuaded President Truman to disband the OSS as of October 1, 1945.

73

The surviving intelligence agencies began competing for the remains of Donovan’s organization. The War Department took over the OSS counterintelligence section, where it became the Strategic Services Unit after its entire staff threatened to resign if they were forced to work for Hoover.

74

As a result, the task of detecting Soviet spies became split between the FBI and the Army, a division that would later have tragic consequences. The State Department obtained the political intelligence section of OSS, including all its files.

[6]

Reinhard Gehlen benefited from this struggle. Each of the American agencies coveted his services, and he dictated a high price for them. Gehlen entered into a pact with the U.S. government and returned to Germany in July 1946, where he was permitted to establish his own intelligence empire. He was under contract to the Americans with the understanding that once a German government was established he would be transferred to its authority. (On April 1, 1956, Gehlen became chief of the Bundesnachtrichtendienst (BND), the official intelligence service of the Federal Republic; he retired in 1968.)

The U.S. Army and Navy, State Department, and the FBI were each to receive the intelligence Gehlen produced, but access to his original sources would be strictly limited. Gehlen had good reason to be cautious. He needed to keep the Americans from learning how badly his organization had been penetrated by the Soviets during the war. He possessed a pipeline to the Soviet Union all right, but it would be years before the Allies learned that the pipeline flowed in both directions.

Upon his return to Germany, Gehlen began to reassemble his staff of intelligence analysts at his headquarters at Oberursel, near Frankfurt. Former members of the FHO staff in American prisoner-of-war cages were surreptitiously released to Gehlen’s custody. American military law prohibited him from employing war criminals and ex-members of the SS or the Gestapo, which had been indicted as criminal organizations at the Nuremberg Trials, but Gehlen reasoned that what the Americans did not know would not hurt them. Blacklisted men were hired and given aliases and false personal documents so he could claim he knew nothing about their past associations. Only one problem remained: Where would Gehlen obtain sufficient amounts of raw intelligence for his machine to digest and process? The Americans were pressing for immediate results to justify the substantial amount of money, not to mention the risk involved, in setting up the Gehlen organization.

Gehlen had a solution. During much of the war, the headquarters of FHO had been in Smolensk, part of the territory that was intended by the Nazis for absorption into Byelorussia. The leader of the collaborators in Smolensk was an energetic Byelorussian nationalist named Radoslaw Ostrowsky, who had impressed Gehlen and commanded a network of secret informers who could provide a great deal of intelligence. Gehlen learned that Ostrowsky was hiding in the British zone and proposed a plan for collaboration. In return for information collected by Ostrowsky’s network in the displaced persons camps, Gehlen offered him the prospect of protection from prosecution for war crimes, courtesy of his American sponsors.

[

1

] In his interrogations after the war, General Franz Kushel always referred to his 30th Division as the 29th Division, thereby hoping to conceal its combat role in France. Twenty years afterward some American intelligence agencies still bought his deception.

[

2

] The “camp leader” at Regensburg was Franz Kushel. He was later placed in charge of the Michelsdorf DP camp, where the Belarus SS was regrouped.

[

3

] Ironically, the American CIC reports described Ostrowsky’s group as the more moderate faction, and Abramtchik’s as the organization with the most Nazi collaborators.

[

4

]Early in 1945 General Heinz Guderian, the chief of staff on the eastern front, presented Hitler with a survey of the deteriorating military situation and the strength of the Soviet armies prepared by Gehlen. “Completely idiotic!” the Fuhrer shouted, and demanded that Gehlen be committed to an insane asylum. Guderian angrily replied that Gehlen was “one of my best staff officers” and said he would not have shown the report to Hitler if he were not in agreement with it. “If you want General Gehlen sent to a lunatic asylum,” he declared, “then you’d better have me certified as well.” Hitler relented, but after this both Guderian and Gehlen were on his blacklist (Guderian, Panzer Leader [E.P. Dutton, 19521,p. 387).

Not all of Gehlen’s forecasts were accurate, however. During the early period of the war in the east he tended to be overly optimistic. See David Kahn, Hitler’s Spies (Macmillan,1978), pp. 441-42.

[

5

] The rivalry between the FBI and OSS was intense. When Hoover learned that the OSS had penetrated the Spanish embassy in Washington and was secretly photographing code books and other documents belonging to the Franco regime, he decided to put an end to it. One night after the OSS had broken into the embassy, two FBI cars pulled up in front of the building and turned on their sirens. The entire neighborhood was awakened, and the shaken interlopers fled. Donovan protested to the White House, but instead of reprimanding Hoover, the President ordered the infiltration project turned over to the FBI. (R. Harris Smith,

OSS: The Secret History of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency

, University of California Press, 1972, p. 20).

[

6

] The State Department’s intelligence operation was unable to rival the military’s growing dominance of the field because it was hampered by congressional charges that some of the transferees from the OSS had “strong Soviet leanings” (William R. Corson,

The Armies of Ignorance

, Dial Press, 1977, p. 272).

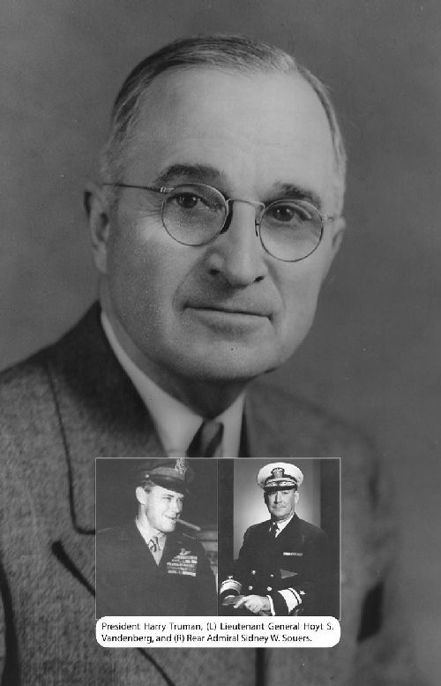

President Harry Truman, (L) Lieutenant General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, and (R) Rear Admiral Sidney W. Souers.

President Harry Truman, (L) Lieutenant General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, and (R) Rear Admiral Sidney W. Souers.

5

Gehlen and Ostrowsky had much in common. Both had the knack of survival, and both were professional conspirators who would serve any master to achieve their goals. And they both had an inordinate amount of luck. Their secret alliance was cemented at a time when their American benefactors were deciding to get into the intelligence business in a massive way. By early 1946 President Truman realized he had made an error in dismantling the OSS and he undertook the creation of the Central Intelligence Agency. “Conflicting intelligence reports flowing across my desk from the various departments left me confused and irritable, and monumentally uninformed,” he complained.

75

The first step was the organization of a Central Intelligence Group to regulate the information that flowed into the White House from the State Department, the military services, the FBI, and a myriad of other sources.

76

The President wanted an intelligence service that would tell him what the Russians were up to. But Truman’s choice as Director of Central Intelligence was less than inspired. Although Truman was an admirable man in many ways, the President’s idea of good government was to give a friend a job. Rear Admiral Sidney W. Souers was one of Truman’s poker cronies who had owned the Piggly Wiggly stores in Memphis and then operated an insurance office in St. Louis before offering his wartime services to the Navy. Two days after Souers was sworn in there was a party at the White House in which Truman jokingly presented him with a black hat, a cloak, and a wooden dagger. Souers was out of his depth and was replaced within six months by Lieutenant General Hoyt S. Vandenberg, who had commanded the Ninth Air Force in Africa and Europe. He was no stranger to Soviet affairs, having served as chief of the U.S. Air Mission to Russia from 1943 to 1944.