Among the Bohemians (37 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

This was an extreme state of affairs, ripe for a revolution, and Bohemia was preparing its subversion with a vengeance.

The radical rejection by many artists of the rituals of domestic perfection, including cleanliness itself, can only be appreciated in the context of those times.

The almost neurotic obsession with domestic efficiency peaked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period when housework was a full-time occupation for innumerable women, and when consumption was nothing if not conspicuous, above all in the home.

The excesses of upholstery, lace, glass, metalware and china all needed exacting attention.

This was the era of the knick-knack, a time when homes were adorned on all surfaces with decorative odds and ends.

It was also a period when internal architecture was perhaps fussier and more convolute than ever before.

Keeping such establishments spruce and spotless was immensely onerous, even if in those days the burden fell largely on servants.

Despite a sharp decline in the servant population (nearly half a million women servants took jobs in factories during the First World War and never returned), the assumption that domestic work was performed by cooks and maids died hard.

‘Every family that can afford to do so will probably employ one or two or more servants,’ wrote Lady Troubridge in 1931.

How did one keep one’s home up to the mark if one could not afford servants?

Luckily

Mr

J.

G.

Frazer had the answer to that.

Her book

First Aid to the Servantless

sets out to demonstrate that ‘Lucy’ can get through the housework without any help at all, having obtained a marvellous break-through gadget called the ‘Ukanusa Drudgee’, ‘which with one pull wrings the cloth and which makes the duty of floor-scrubbing more of a game than a drudgery’.

Polishing her floors with beeswax and wiping them with turpentine keeps Lucy and her Drudgee busy all morning.

In any spare moments the young wife is gainfully employed practising those little economies that make all the difference in the servantless household.

She boils fragments of soap in ajar to make soap jelly, or reuses wooden skewers to clean out tricky corners.

Her day is just one long carefree round of pleasure, causing Mrs Frazer to burst into verse:

The end drudgery

L’ALLEGRA

… Now you must

Fight the dust.

Mop it, wipe it,

Brush it, swipe it,

Rub it, scrub it,

Till all is shiny

Like the briny

Ocean in the sun;

So that when you’ve done,

Not a particle

On any article

Remains above…

*

So fold up the papers,

And blow out the tapers,

Put out the last light.

Good night! Good night!

So may every day

Glide away,

Ever busy, happy, gay,

Ever l’Allegra!

Even with a Drudgee housework took all day, and no wonder.

Until well into the post-1945 era, many British women were still using cleaning equipment which had barely evolved over three centuries.

In the 1920s, before modern detergents, washing up was done with soda, which left the hands raw.

An alternative was soft soap, horribly slippery, so that breakages were frequent.

Vinegar and silver sand or Vim and wire wool were used for scouring saucepans – punishing work.

Stainless steel did not exist, and knives had to be cleaned in a machine using a kind of emery powder.

You stuck the knife into a slot, poured in the powder, and wound the handle like an organ-grinder.

Keeping the house warm was particularly time-consuming and unrewarding.

Six shivering months of every year were dominated by fire-stoking, grate-riddling and ash-disposing.

Some rooms just never seemed to get warm, and life was a battle with damp and draughts.

Until the advent of automatic washing machines, washday was – exactly that: an entire day devoted to washing.

Mrs Beeton recommends an early

start on Monday morning.

Very few British homes owned washing machines before the 1950s, and irons were non-thermostatic.

Those who could afford it ‘put out’ their washing to the private laundry or washerwoman round the corner.

But for many, there was a moral pride attached to home-washing, and it would appear that undertaking the lengthy and skilled task of doing one’s own laundry gave the housewife a particular kind of self-esteem.

*

Housework and laundry were complicated enough, but personal cleanliness had its own special apparatus of ritual and adversity; this too helps place the Bohemian revolution in context.

Take bathing.

Even in the best-run households, like that of Ursula Bloom in her country vicarage, taking a bath was a ‘morning horror’.

Ursula would lie in bed quaking while the servant brought a tin tub coated in chipped enamel up to her room, placed it on an enormous bath mat, and poured cold water into it.

Another servant

*

staggered upstairs with a can of boiling water which she then added.

The trick was then to avoid being either scalded or frozen, and it was one which Ursula never managed to pull off.

However little cold water she mixed in, it was always too much, and the result was a shallow, tepid bath, in which she sat hunched and shivering: ‘Nobody ever had a decent bath, how could they?

After all the hard labour entailed to get the bath into the room and the hot water heated and up the stairs, the result was a tragedy.’

Even properly plumbed bathrooms in private houses were far from being places of luxury and indulgence.

Having a bath was regarded as a utilitarian and no-nonsense activity, so they were generally floored with hygienic linoleum; Sybille Bedford remembered how such places were equipped with yellow coal-tar soap and tooth mugs full of disinfectant.

But one of the most excruciating ordeals imposed by conventional society on its cowed members was the compulsion to deny the existence of lavatories, and above all to deny the activity that took place in them.

No decent person did it [remembered Ursula Bloom], most certainly no lady.

Regarded as the height of vulgarity, whatever personal discomfort or danger it entailed, one was secretive about it… The fact that it was a necessity to man, and to rich and poor alike, was disregarded.

Nobody who was anybody tolerated it.

Thus the accommodation provided was as nasty and uncomfortable as was humanly possible; to have made the lavatory at all commodious would have been to endorse the existence of urination and excretion.

Though non-absorbent toilet tissue was available, one was just as likely to be provided with torn sheets of newspaper.

The disownment of natural functions made outings particularly agonising.

Public lavatories were few and far between,

*

and ‘restaurants were equipped with nothing so immodest’.

Mrs Bloom and another of her daughters nearly fainted once on a shopping trip to London:

In the end someone took pity on them, and they were escorted into the indignity of a back yard where something rudimentary was arranged behind convenient packing-cases.

They never forgot the experience.

*

Were these people mad?

What was it about lavatories and dirt and draughts and damp beds that so haunted the upper echelons of late Victorian and Edwardian society?

It must be conceded that their obsessive attention to cleanliness had a sound basis.

Public programmes of sanitation and vaccination, alongside improved public health and hygiene, have done much to dispel the fear that was a terrifying reality for generations of British people.

Tuberculosis, for the most part communicated to humans via contaminated milk, was thought at the end of the nineteenth century to account for nearly 15 per cent of

all

deaths in this country.

Well into the twentieth century, many people were still alive who vividly recalled the terrible typhus and cholera epidemics of the previous one.

The denial of lavatories was a denial of disease and death, which stalked its victims by way of bad drains, ill-ventilated houses, dirty bathrooms, verminous kitchens.

The only weapon against these plagues was scrupulous cleanliness.

Locked into an unwinnable fight with the forces of dirt and darkness, Victorian and Edwardian housemaids were dusting for their lives.

Against this terrifying backdrop, the squalor so often associated with Bohemianism appears reckless, defiant or fearless, depending on your point of view.

The effrontery with which these people abandoned middle-class aspirations to tidiness and hygiene was neglectful and slovenly, but it was also audacious.

This was a revolution.

‘Sanitation be damned, give me Art!’ cries Somerset Maugham’s fictional Bohemian Thorpe Athelncy: he has been told

his family must move out of their beloved home, which has been condemned for having bad drains.

Above all, it was by turning its back on washdays and clean paintwork, by choosing to live in squalor and dirt, amongst vermin and bugs, that Bohemia came to acquire its dubious and unsanitary reputation.

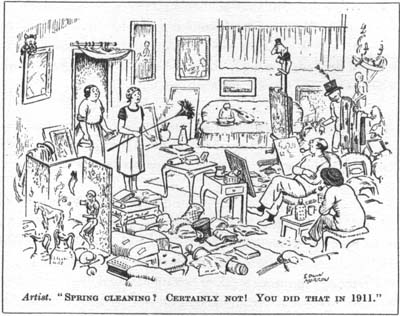

The abandonment of middle-class aspirations (

Punch,

27 April 1932).

Even today, when we are arguably more relaxed about such things, there are those who find the sight of a dirty sink or a grimy bathtub, an unwashed child or mouldy food disturbing, even threatening.

The abyss is full of putrid substances – filth, ordure, the inadmissible scum and refuse which we attempt daily to deny.

Purity is blessed, but uncleanliness is next to ungodliness.

To the outside world there was something almost diabolical about the festering conditions in which Bohemia chose to live.

Nevertheless it is no exaggeration to say that the

âmes damnées

who plumbed those depths did so not from innate immorality, but affirmatively, provocatively, even honourably.

*

For there was another way to live, a way which was labour-saving, sloppy, but also uninhibited and imaginative.

There was a world where neglect of housework was positive rather than reprehensible.

At the turn of the century something of this mood was already in the air.

Cultured Victorian intellectuals felt themselves to be above the petty

keeping-up of appearances, while Utopians like Edward Carpenter had suggested creating a society where everyone’s possessions were held in a common repository, thus bringing about a simplification of architecture and interiors, and at a stroke releasing half the human race from their domestic captivity – no more horse’s hoof inkwells to dust, or crystal decanters to clean.

Meanwhile, some nineties aesthetes, taking their cue from Baudelaire and Huysmans, made a point of plumbing the depths.

Mood, sensation, receptivity was all.

‘When I am good, it is my mood to be good; when I am what is called wicked, it is my mood to be evil,’ says Reggie Amarinth in Robert Hichens’s

The Green Carnation

(1894):