Among the Faithful (21 page)

Read Among the Faithful Online

Authors: Dahris Martin

Elmetboostah boasted nothing so bizarre as a timepiece, but it must have been very late when the party broke up reluctantly, consigning one another to Allah’s care. The door was bolted and, in

a matter of seconds, the lamp was out and the six of us wrapped in our burnouses were lying like logs in a row. Boolowi and Mohammed, on either side of me, sharing my blanket, were instantly asleep. The voluminous folds of my burnous enveloped me like a fleecy tent, my head was cradled in a wooden camel-saddle. Through the tiny

aperture

that served as a window

el Gamar

the moon sent a shaft of white light. For a few minutes Farrah and Kadeja kept up a desultory conversation between yawns, then I, alone, was awake watching the embers in the firepot pulsate and crumble to ash. It may have been hours, it may have been only minutes, that I lay awake. Blackbeetles and fleas in legions seemed bent on consuming me; down the line Farrah and Kalipha snored to Allah. But the crawling of beetles and the nipping of fleas were nothing compared to the acute discomforts of spending a night between two small boys. I was resigning myself to the probability that I would not close my eyes, when I drifted off into a sound and dreamless sleep.

K

ALIPHA’S CHILD WAS DUE

to arrive in the spring; if not in March, then certainly in April. It was now May, the baby had not come, and I was to leave for America on the 15th.

Hope of welcoming the little Mustapha, or Habiba, did not entirely forsake me until the 12th, when I began to pack. How confidently I had promised Kadusha that I would not go before she was delivered! (‘Please God, may all my dear ones be about me when my hour comes,’ she had pleaded.) I had changed my sailing date three times in order to keep my promise. Further delay was impossible. More disappointed than I had ever been in my life, bitterly resentful at the meanness of fate, I made ready for my departure.

But the next morning before I was out of bed Mohammed was yoohooing under my window. ‘Good news,

ma soeur

!’ he shouted up at me. ‘Kadusha is in travail at this hour!’ At the warning pains the midwife had been summoned, and before daybreak Kadusha was escorted to the baths. ‘And now, As Allah is our God, she is seated on the chair!’ he finished breathlessly. He was on his way to fetch her mother. As he sped off he shouted over his shoulder, ‘

Allez vite, alors.

Ils vous attendent!

’ And, indeed, if Kadusha was already upon the natal chair, it behoved me to hurry.

Relief, dread, anxiety, joy – I could not have told what I felt as I plunged into my clothes and hurried through the lanes, where the coloured doors of shops were still shut against the day. I was rushing along the main street dodging loaded burras, carts, and camels, when I heard Kalipha calling me. He and Babelhahj were seated in front of one of the cafés taking their coffees. ‘Where are you going,

ma petite

,’

he chided me serenely, ‘that you run as if pursued by the devil himself?’

‘But don’t you know? Your wife is on the chair!’

The men looked amused. There was still plenty of time, they said, making room for me on the bench and ordering coffee. Because a woman is on the chair – what does that signify? Good Lord, city women were the limit with their theatricals; their midwives, baths, and chairs! Now the bedouine! They reminded each other of how she drops out of the caravan, has her child, ties it to her hip, then presses on to overtake the others. I stayed only long enough to gulp down my coffee, my hands trembling so with nervous fury I could scarcely hold the cup, and left them still deprecating the hullabaloo of confinement.

Numéro Vingt looked somehow mysterious today, as if hinting, very subtly, of the event that was being enacted inside. I rattled the knocker, but no kop-kop-kop of clogs descended the stairs in answer. I rattled it again, this time a little louder. Nothing happened. So I pulled myself together and let it fall – it made, an awful noise. Then, as there was still no response, I thrust myself against the door. It yielded, shrieking. Prepared for the worst, I started up the stairs. Sounds came down to meet me – sounds that my ears absolutely refused to credit. I stepped into the court.

But this was a party! Here were romping children, a score of women togged in their garish best sitting about in little groups drinking tea! ‘

Alla-la-een! Alla-la-een!

’ all shrilly welcomed me. In the midst of the carnival sat Kadusha. Her face under the bizarre make-up was very grey, her ornamented eyes, sunken and sad, but at sight of me she tried to smile.

The natal chair – pale blue, gaudily decorated with the symbols of fertility in red and yellow paint – has sides but no back. There is a

crescent

-shaped opening in the seat to accommodate the descent of the child. The chair is ample enough for two and Kadusha was reclining in the arms of her young aunt, Shedlia, who sat behind her, with legs extended. Dangling within Kadusha’s reach was an orange rag that was attached to a beam overhead. The old midwife, Ummi Banena, was crouched at her feet. She kept up a droning chant while her hands

were busy precipitating the delivery. Just what they were doing couldn’t be seen, for they worked under cover of a shawl that modestly covered her patient’s lap.

Dazed, bewildered, I was drawn into one of the little groups and plied with tea and fête cakes. In my ignorance I had hoped that I might be able to help! There was nothing, nothing I could do except sit myself among the spectators of Kadusha’s pain. She was terribly alone. Even Zorrah, who had been through this so recently herself, was paying little heed to her daughter, although she held her hand. The liveliness of the chatter did not diminish during those intermittent struggles when Kadusha groped for the rag and groaned ‘

Ya Mo-ham

-mud!’ This was a signal for Shedlia to tighten her embrace, for the midwife to invoke with a loud voice the compassion of Allah and His prophet until Kadusha, ceasing to moan and grimace, sank back exhausted.

Jannat smiled at my look of horror. ‘Ah yes,’ she nodded, twisting her hand in an inimitable little gesture, ‘it is like that.’ All of the women, with the exception of Ummulkeer and Eltifa, had been mothers many times, and most of them were pregnant.

Still the guests kept coming, blithely exchanging the compliments of the occasion as they doffed their

haïks

. Solicitude, anxiety, and fear were not to be found at this party. One or two of the women, in contrast to the others, sipped their tea in silence. Inscrutable, equally unmoved by the spectacle – after all, it was such an old story – they epitomized for me the gruesome acceptance that is the women of Islam.

Now a plate was being brought in. It had been prepared by

Abdallah

, and was covered with hieroglyphics traced in brown syrup. A little water was poured upon it, and when the script had dissolved the plate was held to Kadusha’s pale lips. But even the essence of holy writ did not bring an end to her suffering. It was inconceivable that she could bear much more.

In the meantime a vociferous discussion was on, the subject of which was, if I could trust my ears and feeble Arabic, a gramophone! Voices above voices clamoured to be heard. The excitement eventually culminated in the dispatch of Kalipha, who was discovered sitting on the stairs.

My mystification must have been apparent, for together and in

turns they explained to me that a pre-natal craving allowed to go ungratified is liable to leave the direst effect upon the issue. Throughout her pregnancy, it seems, Kadusha had longed to listen to a gramophone.

Kalipha had returned with the owner of the instrument. Steps upon the stairs sent the women scuttling to the far wall, hastily wrapping their

haïks

about them lest they be seen. From the landing the painted horn was extended into the court. Sidi Middib in the doorway, but with eyes respectfully downcast, placed the disk and wound the handle. The thing began to twitter a monotonous falsetto on a theme of voluptuous love-making. The women sat entranced. And, as if the life in her womb responded, Kadusha’s paroxysms intensified. She had seized the midwife’s head in both hands. With all the strength she could summon she laboured, until, bending forward in the extremity of anguish, she yielded her child.

Before I realized it had come there was a concerted lunge toward the chair. The room was full of hysterical cries and confusion. The black disk whirled on, oblivious. Above the deafening lamentations and praises the voice of Ummi Banena announced,

‘B’Araby benáiya!

’ (‘By God! A girl!’) whereupon felicitations, prolonged and piercing, must have roused the long dead, but Kadusha, the colour of death, did not stir. They poked and pinched her, screamed in her ears, drenched her face and head with vinegar, tried in vain to make her drink, and with the first flicker of the eyelids stormed her with congratulations.

Meanwhile the midwife, on her haunches, was trying to make herself heard. ‘

Weni mousse?

’ (‘Where’s the knife?’) she kept shouting. Much dashing about produced a rusty razor, Awisha was sent flying to a neighbour’s for a bit of cord, and at long last the tiny entity was inserted into her shirt. But she must wait again until they tore one of Ummi Sallah’s garments into strips, for it is propitious to swaddle the baby at first in the cast-off garment of an aged woman. So, all bound in cotton pieces, Kalipha’s daughter Habiba was handed up, blinking and mouthing, to be kissed all around, then stowed away in the bed.

The excitement subsided. Sidi Middib went away, the machine on his head. The midwife, having washed her smeared hands, was burning incense upon the fire-pot; her eerie incantation was to exorcise

the djinns that all might go well with mother and child. Kadusha, still upon the chair, was acknowledging congratulations and giving directions for the old woman’s refreshment. Finally she rose and, without assistance, walked from the court into the room and got into bed, where she sat up arranging her dishevelled garments. As many of the women as could took seats beside her. Kadusha made room for me, insisting, until I too found myself on the bed. And as long as I remained she didn’t once lie back but sat up, unsupported, entering into the conversation with the energy of a convalescent of some slight indisposition!

While the midwife was eating in the corner, Ummulkeer and Shedlia cleared room for themselves on either side of Kadusha and began energetically kneading her loins and thighs. When they were satisfied that they had dislodged any djinn that might have lingered there, each of the girls placed a bare foot against Kadusha’s cheek and taking hold of her hands they pulled, straining backward as far as they could. Then they pulled her legs. Even a bedouine couldn’t have endured these exercises more stoically than Kadusha! The sweat stood out on her forehead and she smiled wearily when they told her that they had done. All that remained for her to do was to eat a small handful of

camoon

, or cloves, for the expedition of her recovery. Some cloves were sprinkled upon Habiba, and after her eyes and mouth were washed out, she was placed at Kadusha’s breast. The deep look of love she gave the little stranger as she tucked the nipple into that button mouth!

Her meal over, the midwife did not delay her departure. The guests each contributed a pittance toward the payment of her fee, as was customary; Ummi Banena put her withered lips to the baby’s brow and, after a profusion of blessings, went her way. The natal chair would follow on donkey back. As if her exit was their cue, the guests began to don their

haïks

. ‘

Inshallah mandiksow

,’ they told Kadusha in farewell, ‘May Allah bless thee and thine.’ ‘

Inshallah farhat Habiba!

’ ‘If it be the will of Allah, may Habiba marry young and prosperously.’

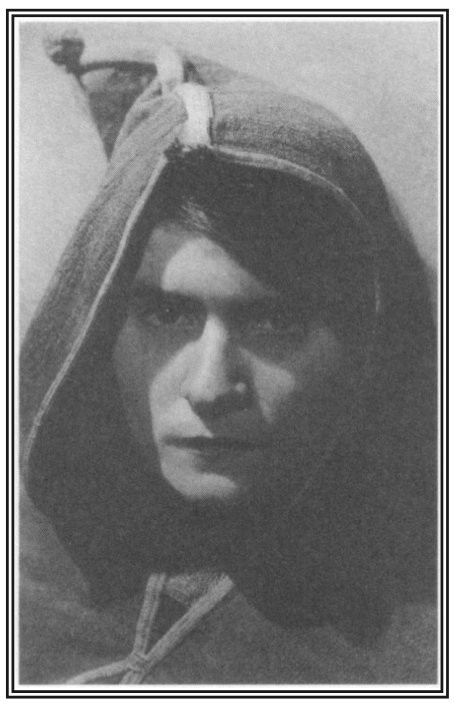

THIS PHOTOGRAPH

shows Dahris Martin wearing a Tunisian

burnous

at the time of her stay in Kairouan, and was taken by the American photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe in the late 1920s.

Dahris Martin was born in New York State around the turn of the century. She studied at Columbia University and worked for Doubleday before setting off for Europe to concentrate on her own writing.

Among the Faithful

was first published in London in 1937, but with the arrival of American troops in Tunisia during the Second World War, it was taken up and republished in New York as

I Know Tunisia

(1943). Dahris Martin wrote a number of Tunisian tales for children, including

Awisha’s Carpet

and

The Wonder Cat.

She met her future husband, the New England print-maker Harry Shokler, while living in Tunisia.

61 Exmouth Market, London EC1R 4QL

Email: [email protected]

Eland was started in 1982 to revive great travel books which had fallen out of print. Although the list soon diversified into biography and fiction, all the titles are chosen for their interest in spirit of place.

One of our readers explained that for him reading an Eland was like listening to an experienced anthropologist at the bar – she’s let her hair down and is telling all the stories that were just too good to go into the textbook. These are books for travellers, and for those who are content to travel in their own minds. They open out our understanding of other cultures, interpret the unknown and reveal different environments as well as celebrating the humour and occasional horrors of travel. We take immense trouble to select only the most readable books and many readers collect the entire series.

Extracts from each and every one of our books can be read on our website, at www.travelbooks.co.uk. If you would like a free copy of our catalogue, please order it from the website, email us or send a postcard.