Amy & Roger's Epic Detour (10 page)

My mother, coming back to the table with her mug of tea, smiled and shook her head. “I told you they were too abstruse, Ben,” she said. I didn’t know what that meant but, as usual, Charlie seemed to.

“They’re

clues

,” my father said, not seeming to be put off by our reactions at all. “To where we’re going this summer.”

I held up my book. “I’m guessing Memphis?” “Yes,” said my father with exaggerated patience. “But not just anywhere in Memphis….”

Charlie rolled his eyes and set his book down. “Graceland?” he asked, and my father nodded.

Seriously?

he mouthed to me across the table. I ignored him.

“Yes!” my father said, taking the book from me and flipping through it. “I was thinking about July. So clear your calendars, you two, we’re calling on the King.”

Charlie shook his head and pushed the book away. “No offense, Dad, but Graceland’s kind of lame.”

“Lame?”

my father asked, mock-outraged. He turned to my mother for support, but she just smiled and shook her head, already flipping through the

New York Review of Books

, staying out of the conflict like she always did.

“It’s not lame,” I said, taking my present back from my father and paging through it.

“Have you been there?” Charlie asked.

“Have you?” I retorted, glaring at my brother. I didn’t know why Charlie always had to be so difficult, and why he couldn’t just go with something for once. It wasn’t like Graceland was the first place I wanted to go either, but clearly it was important to Dad. Which, as usual, Charlie didn’t seem to care about.

“Your sister makes an excellent point,” my father said, and I heard Charlie mutter, “Of course she does,” under his breath. “As the only one sitting at this table who has been to Graceland, I can attest to its non-lameness. It’s an American institution. And we’re going. We’ll pack up the car—”

“Wait a second.” Charlie sat up straight. “We’re driving? To

Tennessee

?”

“We’re going to discuss that,” said my mother, looking up from her paper. “It’s a long way, Ben.”

“No better way to see America,” my father said, leaning back in his chair. “And when we get to Memphis, we’ll see Beale Street, and the ducks at the Peabody, and get some barbecue….” He turned to me and smiled. “You ready to navigate, pumpkin?”

She’s gonna make a stop in Nevada.

—Billy Joel

“Are we headed the right way?” Roger asked, glancing over at me. I pushed his sunglasses up and rotated the map. I had directed us out a different way, since it had looked easier to leave through the other side of Yosemite, rather than retrace our path to the park entrance.

“I think so,” I said, looking at a sign as we neared it. But it was completely covered by the branches of the tree next to it. I could only see a strip of green at the top. “Oh, good,” I muttered.

“I’m just a little turned around,” said Roger, peering ahead of him.

“We’re okay,” I said, seeing, relieved, a sign that wasn’t overgrown with branches and told us which way to get to the highway. “Just take the right up here.”

“I’m glad you’re on top of this,” he said, making the right. “I’m not the greatest with directions. And I can never tell when I’m lost, either. It’s a bad combination, because I always think that if I just stick with the road long enough, it’ll all work out.”

“Well, I’m good with maps. So I’ll navigate,” I said, speaking around the lump that was threatening to form in my throat.

“Excellent,” he said. “You’ll be my Chekov.”

I looked over at him. “Anton Chekhov?” I asked. “The playwright?”

“No, Chekov, the navigator of the Starship

Enterprise

,” he said, looking back at me. “From

Star Trek

.”

“I’ve never seen

Star Trek

,” I said, breathing out a tiny sigh of relief. Maybe Roger wasn’t quite as cool as he’d first seemed.

“Now that’s a tragedy,” he said. “Though I must admit, I’ve never read your Chekhov.”

The road, as we left Yosemite, became more winding and more deserted. It was just a two-lane road, and as we made increasingly sharp turns, it became clear that we were in the mountains. As I looked at the pine trees surrounding us, it seemed impossible that we were still in the same state we’d been in yesterday, with freeways and palm trees.

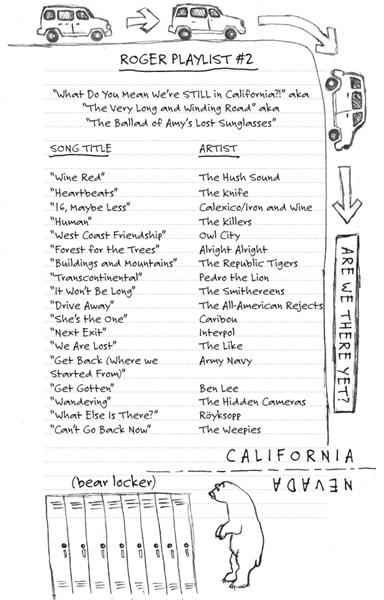

“You ready to put on some of your music?” Roger asked, as his mix started over again.

“That’s okay,” I said. My suspicions that Roger didn’t like musicals had been confirmed when I’d seen his playlist. He seemed to like the kind of music that the in-the-know people at school always seemed to be talking about, the kinds of bands with names that didn’t even sound like real names at all. Someone Still Loves You, Boris Yeltsin? That was a band? A real band, with fans other than Roger? So I had a feeling he wasn’t going to be into my selection of Jason Robert Brown and Elvis. And I wasn’t listening to Elvis anymore, anyway.

“Really?” he said. “I don’t want to keep hogging the DJ job.”

“It’s fine,” I insisted. I didn’t want to have to watch him pretending to enjoy my music, or just tolerating it, waiting until he could switch back to his stuff. It was easier to keep listening to his. And I found that I actually liked a lot of it.

“Want to at least give me an indication of what you like?” he asked.

I shrugged, wishing he would stop grilling me about this already. “I like everything.”

Roger shook his head. “Such a cop-out,” he said. “If you like everything, that’s basically just saying that you don’t really like anything.”

“I like stuff,” I snapped, sharper than I meant to sound. “I just don’t care, okay?” I stared out the window, immediately regretting my words. I did this a lot lately—I would suddenly get angry for no reason. That was why it was easier just not to talk to anyone.

“Well, okay,” he said after a moment. “When we reach civilization, I’ll make a mix.”

“Just no Elvis,” I said, looking out the window.

“Not a fan of the King?” he asked, and I could feel him looking at me.

I shrugged and pulled my knees up, wrapping my arms around them and staring out at the scenery passing by. “Something like that,” I said.

Two hours later we had passed through the towns surrounding Lake Tahoe and were heading toward the Nevada border. When it had become clear after about an hour or so that civilization was not going to appear right around the corner, we had pulled over to the side of the road and Roger had compiled his new mix. While I had known California was big, I had never realized just how big until now. It seemed impossible that we were still in the same state. We’d had a lot more mountain scenery for a while, more rocks and pine trees and sharp turns. But things had begun to flatten out a bit, and Highway 50, the winding two-lane highway we’d been on since leaving Yosemite changed to four-lanes, with two going each way.

As Roger’s new mix started for the second time, he slowed the car down and pulled it over to the side of the road. I looked over at him, and he nodded ahead of the car. “I thought we had to stop and mark this moment,” he said, pointing. “Check it out!”

I looked, and there it was—a smallish white sign, with blue letters that spelled out

WELCOME TO NEVADA

. And then, below that, the silver state

.

“Wow,” I said, staring at it.

“Leaving California,” Roger said. “How’s it feel?”

“Good,” I said, without even stopping to think about my answer.

It did feel good. It was what I’d been thinking ever since I’d felt the desire to get out of Yosemite. It was the impulse to turn a new page, to put some distance between myself and California and everything that had happened there.

“So,” said Roger, reaching into the backseat and picking up the atlas, “do we know which way we’re going?”

“Yes,” I said, taking the atlas from him and flipping to the page for Nevada, which suddenly looked worryingly big. And we were crossing it at the widest point, not the little tip of it you’d drive across if you went the southern route. “So here’s the thing. There are only two interstates that run through Nevada. Eighty up by Reno, and 15 down by Vegas.”

“Vegas?” Roger asked, peering at the map.

“Right,” I said. “The Reno one is closer to us at this point, but it’s still out of the way. And that puts us way up by Salt Lake City, which seems really far out of the way.”

“So what’s the plan?” he asked.

“Well,” I said, tapping my finger on where we were, “right now, we’re on Highway 50. And it looks like that will take us all the way across Nevada and into Utah. And then a little ways into Utah, we can get onto Interstate 70.”

“There are no interstates that go through the middle of Nevada?” Roger asked, looking over at the map. “Huh,” he said, after staring at it for a moment. “There really aren’t, are there?”

“But I think that’s our best bet,” I said, studying the map. As I did, I realized that in terms of logistics, Yosemite hadn’t been a great pick. It had taken so long to get to, and so long to get out of, and now it seemed it was going to be challenging crossing Nevada. Apparently, not many people chose to leave California by way of a national park. “Think we’re still going to be okay with the time-line?” I asked, acutely aware of the fact that we were supposed to be closing in on Tulsa at the moment, not just venturing out of California.

“Probably,” said Roger, still looking down at the map. “I’m sure we’ll be able to make up the time. And I think your mother will understand if we’re a day late.”

I wasn’t so sure about that, but I nodded. “So where should we head?” I asked. “I picked Yosemite. Where do you want to go?”

“Well,” Roger said, glancing up at me for a moment, then back down at the map, and flipping to the page for Colorado. “It looks like if we get on the interstate in Utah, and follow that through Colorado, we’ll hit Colorado Springs.”

“Pretty close,” I said. It wasn’t, exactly, but it was close-ish. I looked up at him, surprised that he would want to go someplace he’d already been. “Is that where you want to go?”

“Well, it might make sense,” he said, not looking at me but fiddling with the volume on the iPod. “We’ll definitely have a place to crash, free. And I can show you around the campus, see which of my friends are around….” He said this last part very quickly.

“Sure,” I said, turning the pages back to Nevada. “That’s fine with me.”

“Great,” he said, looking incredibly relieved. “So, Highway 50?” he asked. “Shall we?”

“Let’s,” I said, nodding, and Roger signaled and pulled back on the road.

After two hours, we realized something was wrong. The highway had switched from a four-lane road to a two-lane road at some point, with one lane going in each direction. But that in itself wasn’t worrying, as we’d encountered several stretches of those near Yosemite. What was different was that suddenly there just wasn’t … anything. The road stretched out ahead of us, a straight line extending as far as I could see. There were mountains in the distance in front of us and mountains in the distance behind us, but mostly there was just a huge, open, deserted landscape, cut down the center by the two-lane highway. And nothing else. The flatness of it was a big change from the winding mountainous roads near Yosemite. There were what looked like scrub brushes on the side of the road. I found it hard to believe that only a few hours ago, I’d been surrounded by pine trees.