An Appetite for Violets (4 page)

Read An Appetite for Violets Online

Authors: Martine Bailey

NOTICE

A Lady of Age & Most Estimable Experience, most genteel, the daughter of a much admired late Suffolk clergyman, who understands the business of making up clothes and linen, is dextrous with a needle, dresses hair admirably, & possesses the benefits of a genteel private education, would wait upon a respectable Lady and make herself useful in any Capacity such as Maid, Nurse or Companion. Most eager to take up a suitable position without the slightest delay. Please reply in the strictest confidence to Miss J at Mrs Wardle, Haberdashers, The Strand.

Being the day before Souling Night, October 1772

Biddy Leigh, her journal

To Make A Fricassee of Chicken

Take your chickens fresh killed and cut in pieces and brown them quick in butter. Have some strong gravy, a shallot or two, some spice, a glass of claret, a little anchovy liquor, thicken your sauce with butter rolled in flour. Garnish with balls of forced-meat, cockscombs and toast cut in triangles all around.

A dish given to me by a Tavern Cook at Preston as being in the great court style, Martha Garland, 1743

That Jesmire creature was indeed in my kitchen, peering at the row of spoiled tarts. She was dabbing a handkerchief to the tip of her pink nose.

‘What in heaven’s name are those?’

‘A small accident,’ I said shortly. ‘So what can I do for you?’

‘Lady Carinna requires some chicken cooked nicely,’ she announced, pursing her vinegar lips. ‘But you will have to do better than this. These will never do.’

Oh, I was right ashamed she’d even seen them.

‘Of course I’ll do me best for her, ma’am.’

With a snort my visitor began to peer about the kitchen.

‘So, the chicken. Dress it as well as you are able. The diner is – a true gourmand.’ A nasty twitch played at the corners of her lips.

I’d been looking her up and down and decided she was nowt but a servant like me. Her fancy green gown was plainly a hand-me-down too large for her frame – she were a pilchard dressed as cream, as Mrs Garland would say.

I stopped nodding and glared. ‘So are you fetching it up then?’

You would have thought I’d told her to mop the floor.

‘Me? Why, I have never lifted a plate in my life. Loveday, my lady’s footman, will come down for it. I am taking the carriage directly. Well, get to it, girl.’

* * *

Sauce-box! I racked my head to remember the fine old dishes that Mrs Garland used to make for Lady Maria. Fricassee, I settled on, for it had a fancy French sound to it. I browned the chicken in my pan and dressed it up with the proper garnishes.

No one came. That footman of hers – was he also too tip-top to fetch and carry? With a curse I sent the hall boy upstairs. Moments later his sleepy head reappeared.

‘There in’t no one there, Biddy.’

With a cuff to his head I decided to take it up myself. There were no backstairs at Mawton to keep us servants out of sight, though I reckoned little then how unmannered that must seem to the Londoners. Since my first day’s hiring I had loved Mawton’s castlements and crumbling towers, the black panelled halls and creaking stairs. It was built in the pattern of great houses hundreds of years past, with new parts clustered about a chilly keep tower from the days of the Conqueror. To pass above stairs was a rare treat for me, like visiting a palace of wonders, a chance to feel soft Turkey carpets beneath my boots and gaze at the shining pewter chandeliers.

On the stairs the pictures slowed my pace. Above me in a golden frame, Sir Geoffrey looked lordly in his ermine gown, and much more personable aged forty than he did now he was more than sixty. Yet even then his gaunt cheeks and thin lips foretold his coming ruin. What in God’s own name did his young bride make of her new husband? I remembered the first time I’d seen him in this very same place. Not long after I’d arrived at Mawton I’d been summoned upstairs to help choose herbs for the linen. Afterwards, I’d fancied myself alone, and loitered to admire these same paintings. At the sound of a tapping cane growing ever closer, I’d frozen stock-still. It was too late to hurry off downstairs, so I drew back against the wall as Sir Geoffrey himself appeared above me. I saw him for only a moment, but his countenance was one I would never forget. Unlike his portrait he was a wreck of a man, his white hair hanging in greasy tails, and his back bent beneath a faded velvet coat. Two pale eyes lifted from his florid face, meeting mine for an instant and narrowing in annoyance. His eye rims, both upper and lower, were unnaturally scarlet.

Mrs Garland’s instructions suddenly rang in my ears. ‘Biddy, if you should ever meet the master, turn to the wall.’ I swiftly turned about, dropping my head and praying with eyes screwed up tight that he might not speak to me. He lumbered closer, his cane thudding on the floor as he dragged himself behind it. As I held my breath he passed me like a frost creeping through the night. Long ago he’d been good-tempered, by all account. ‘When he married Lady Maria he treated the whole village to a roasted ox,’ Mrs Garland had told me. Yet all I’d ever known of him were tales of drunkenness and vicious harangues at any who crossed him. I pitied the young mistress, fleeing up here and fretting for his return.

Beside his portrait was a dainty picture of his first wife, Lady Maria, her timid face as pale as a pearl. Every inch of her was bedizened with jewels and lace, and at the picture’s heart her thin fingers dandled the ruby called the Mawton Rose. For hundreds of years it had been kept at Mawton, after being ripped from a saint’s grave by one of Sir Geoffrey’s ancestors. It had been painted very finely, every sparkle tricked as if it stood before your eyes. The foolish tale was that the jewel had leached away Lady Maria’s strength, so all of her babes miscarried, and she herself was dead at less than five and twenty.

Mrs Garland had known her, when first she came to Mawton. A fine confectioner she called her, and said it was true that the poor mistress had worn the jewel night and day, till Sir Geoffrey had finally plucked it away as she lay cold in her coffin. She was long dead, of course, with no remembrance at all save by us, who made free with the ruins of her precious old stillroom.

* * *

No footman waited at Lady Carinna’s door. So there was nowt for it but to knock. No one answered, so I knocked again. Finally, I heard a weak voice. Inside, I found only Lady Carinna all alone. God’s tripes, I swore under my breath. I was not at all used to serving gentlefolk.

‘Me Lady,’ I racked my brain-box for polite words. ‘I’ve fetched you your dinner.’

She was propped up on the vast four-postered bed, almost hidden by its twisted pillars and blue brocade. The room was so thrown about with cloths and chests that I had to be mighty careful with the tray as I made my way towards her.

She flicked a limp finger towards the table at her bedside. I set down the tray and took a quick look about me. She was lounging on the bed in a gaping lilac gown, and showed a pair of white stockings with dirty grey soles. Scattered on the quilt were the remains of a cake, and a greasy rind of ham. Honestly, I wanted to spit, I was that offended at her fetching her own dinner.

She was staring at a letter, a frown between her painted brows. There were signs of tears, too, in the pink rings about her eyes. I was so busy gawping I almost cried out when one of the heaps of silk suddenly shifted and moved. An ugly little face pushed out from beneath the bedclothes. It was that poxy dog.

My mistress sniffed at the plate and pulled a face. ‘Scrape that stuff off,’ she said, pointing at my stately garnish of toast and cockscombs. Some people just don’t know fine food when it’s put in front of them.

‘Cut it up,’ she demanded, as I curtseyed in readiness to leave. So I set about cutting it, wondering that a lady such as she could not even master her own knife. With another small curl of her finger she bid me come closer with the dish. And then I had to stand as still as a sentry with the plate held before me for a full ten minutes as she fed the dog my perfectly fricasseed chicken. What had that old toady said? ‘The diner is a gourmand.’

Oh my stars, she would pay for that one day.

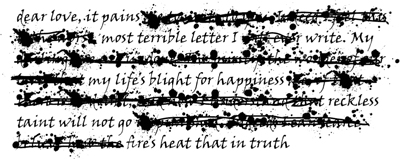

Whenever the dog distracted his mistress I looked about myself. She had set down the letter she had been so mighty interested in and folded it over so I could make nothing of it. That she had been trying to answer it I could see from the balls of crumpled paper thrown around. I did my best to spy them out and found I could read a little of one of her crumpled fragments. It had been crossed out so hard that the paper was torn right through. Ink blots smeared much of it but I did my best to cipher it:

It made no sense to me at all, for only gibberish words were left. Yet even I could comprehend her unhappiness. What was Sir Geoffrey thinking to grieve the girl so? It was a tragic case indeed.

Finally the lapdog turned his head aside with a yap of temper. Lady Carinna fell back on her bolsters, all exhausted. Staring absently into space, she nibbled at nails that were bloodied to the quick. I suppose her looks passed for beauty in London, for her complexion was as smooth as a boiled egg. Yet her rosebud lips were cracked beneath the carmine, and her hair, half-down to her shoulders, had little powders of scurf. Then I remembered she was an abandoned bride and to be pitied.

‘Me Lady. Is there nowt else I can fetch you?’

She didn’t even look at me, only shook her head while lifting the letter to read it again. I retreated to the door.

‘Wait. Can you fetch me these?’ She picked up a ribbon-festooned box of sweetmeats. ‘Jesmire,’ she said, as if the word tasted like a sour lemon, ‘has gone to look for some, but I doubt she will succeed.’

‘Can I see?’ I hesitated and then at her nod, came forward and peered into the paper-layered depths. A fragrance rose from the wooden box of fine sugar and a pulsing scent that one moment delighted and the next disgusted, like charred treacle.

‘Violet pastilles?’ I ventured.

I took her silence for agreement.

‘You won’t find them in these parts,’ I explained. ‘Yet I could have a go at making them.’ My blood was still up, from the offence I’d taken over my fricassee. ‘Well,’ I shrugged, ‘I could make summat like ’em. I pride myself I can cook almost any article I taste.’

I pride myself. Puff-headed words.

‘What did you say? Damn it, girl, I can barely comprehend your foxed speech. You could make them?’ From her grimace you would have thought I had told her to pin them in her hair. ‘Why, these are from

The Cocoa-Nut Tree

at Covent Garden. You have heard of that establishment?’

No doubt she expected me to scratch my head like a right country numkin.

‘

The Cocoa-Nut Tree

at Covent Garden? Why it’s the finest confectioner in the capital and sells bonbons, macaroons, candied fruits, and ices,’ I said in my proper reading voice. I had long studied their advertisement in Mr Pars’

London Gazette

after he’d left it by the kitchen fire. It was a beautiful advertisement, with little drawings of sugar cones, ice pots, and tiny men attending wondrous stoves.

‘Why, you are quite the monkey mimic, aren’t you?’ I felt her scrutiny like something crawling on my skin. Beneath her slummocky ways she had wits aplenty.

‘Yet I reckon,’ I added quickly, ‘I would need one to copy.’

‘What’s to lose,’ she sighed, falling back upon the pillow. ‘Take one. Your name?’

‘Biddy Leigh, Me Lady.’ I curtseyed deep.

‘Take one,’ she repeated. ‘But if you cannot make a perfect copy, Biddy Leigh, you must send to London for a whole box, all from your wages. Do you understand?’ I felt a quickening of alarm. A fancy box like that might cost me a quarter year’s wages.

‘You do understand? A perfect copy. Not just – what was it you said? “Summat laak um”.’

She laughed at her aping of my speech, a hoarse chuckle that I did not like at all. Did I truly sound like a witless beast?

‘Aye, Me Lady.’ I bobbed deep and slipped the sweetmeat in my pocket. As I turned to leave I saw her grasp the ratty dog and begin a new game. She made it dance on its hind-legs while she dandled one of the precious violet sweetmeats, till with a gobble the pastille disappeared.

Being the day before Souling Night, October 1772

Biddy Leigh, her journal

To Make Violet Pastilles

Take your Essence of Violets and put into a Sugar Syrup, so much as will stain a good colour, boil them till you see it turn to Candy Height, then work it with some Gum Dragon steeped in Rosewater and so make into whatever shape you please, pour it upon a wet trencher, and when it is cold cut it into Lozenges.