An Army at Dawn (14 page)

Authors: Rick Atkinson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #War, #bought-and-paid-for

Soon enough, they were also desperately seasick. After wallowing about until dark, the matchwood fleet motored south in three columns at eight knots. At eight

P.M.

, the first boat broke down. Ninety minutes later, the flotilla made way again, only to have two more boats stall. Overheated engines and ruptured oil lines now spread like the pox, with all boats forced to stop during each repair. An east wind rose, and with it the sea, forcing the men to bail with their helmets. At eleven

P.M.

, the corvette H.M.S.

Spey

, assigned to guide the craft to Algiers Bay, darted off to investigate a mysterious radar contact four miles to the east. As the puttering boats waited, a white flare and the roar of 20mm cannon fire tore open the night. When the corvette returned, her chastened captain explained that his men had mistaken landing boat No. 28—lost and headed the wrong way—for an enemy submarine. Fortunately, the shots missed.

Shortly after midnight, boat No. 9 reported she was sinking after colliding with another craft. The men scrambled off and the seacocks were opened. By this time, the flotilla was making less than four knots, with a hundred miles still to cover. Tow ropes broke, engines seized up, retching soldiers by the hundreds hung their heads over the gunwales and prayed for land. Major Oakes agreed to cram the men into seven sea-worthy boats and scuttle the rest, a task

Spey

’s gunners undertook with uncommon zeal.

Even then the cause was lost—the sea too great, the craft too frail. Sodden and miserable, the battalion and its stowaway cook gingerly boarded the

Spey.

With all deliberation, to avoid shipping seas that would wash men overboard, the corvette steamed south, nearly foundered by the burden of an extra 700 men, but determined to invade Algiers, however belatedly.

Some hours passed before Eisenhower learned that the first dire reports about the

Stone,

like most first dire reports, were exaggerated. She was not sinking; her troops had not perished. By the time an accurate account reached Gibraltar, however, he was occupied with a challenge to his generalship more distressing than a mere torpedo strike. The French had arrived.

General Henri Honoré Giraud had been plucked from the Côte d’Azur two days earlier by the ubiquitous H.M.S.

Seraph.

He wore a gray fedora and a wrinkled herringbone suit, with field glasses around his neck; stubble filled the hollows of his cheeks. Nor had his appearance been improved by a partial ducking during the perilous transfer from a fishing smack to the submarine. But his bearing was imperious and his handlebar mustache magnificent. Tall and lean, he marched down the Great North Road tunnel as though it were the Champs Élysées. It was then five

P.M.

on November 7.

In a briefcase, Giraud carried his own plans for the invasion of North Africa, the liberation of France, and final victory over Germany. He stepped into the tiny office where Eisenhower and Clark waited, and as the red do-not-disturb light flashed on outside the closed door, he proclaimed, “General Giraud has arrived.” Then: “As I understand it, when I land in North Africa, I am to assume command of all Allied forces and become the supreme Allied commander in North Africa.” Clark gasped, and Eisenhower managed only a feeble “There must be some misunderstanding.”

Indeed there was. Eisenhower had tried to avoid this meeting in part because the issue of command remained unresolved, and he had even written Giraud an apology for not seeing him, postdated with a phony London letterhead. But when the general showed up at Gibraltar demanding answers, Eisenhower relented.

Giraud was without doubt intrepid. U.S. intelligence reported that his last message before being captured in 1940 was this: “Surrounded by a hundred enemy tanks. I am destroying them in detail.” One officer described him flinging men into battle with a rousing

“Allez, mes enfants!”

Thrusting one hand into his tunic like Napoleon, he used the other to point heavenward whenever he spoke of the noble French army. In German captivity, he signed his letters “Resolution, Patience, Decision.”

But valor has its limits. Giraud, one of his countrymen observed, had the uncomprehending eyes of a porcelain cat. “So stately and stupid,” Harold Macmillan wrote, adding that the general was ever willing to “swallow down any amount of flattery and Bénédictine.” Privately, the Americans called Giraud “Papa Snooks.”

The general’s greatest genius appeared to be a knack for getting captured and then escaping. He had been taken prisoner in 1914, too, but soon made his way to Holland and then England, disguised as a butcher, a stableboy, a coal merchant, and a magician in a traveling circus. His April 1942 flight from Königstein, after two years’ imprisonment with ninety other French generals, was even more flamboyant. Saving string used to wrap gift packages, he plaited a rope reinforced with strips of wire smuggled in lard tins; after shaving his mustache and darkening his hair with brick dust, he tossed the rope over a parapet and—at age sixty-three—climbed down 150 feet to the Elbe River. Posing as an Alsatian engineer, he traveled by train to Prague, Munich, and Strasbourg with a 100,000-mark reward on his head, before slipping across the Swiss border and then into Vichy France.

Now he was in Eisenhower’s office, demanding Eisenhower’s job. Giraud spoke no English, and Clark, hardly fluent in French, labored with help from an American colonel to translate the words of a man who habitually referred to himself in the third person. “General Giraud cannot accept a subordinate position in this command. His countrymen would not understand and his honor as a soldier would be tarnished.” Eisenhower explained that the Allies, under the murky agreement negotiated at Cherchel and approved by Roosevelt, expected Giraud to command only French forces; acceding to his demand to command all Allied troops was impossible. To ease Giraud’s burden, the U.S. military attaché in Switzerland had made available 10 million francs in a numbered account. A staff officer with a map was summoned to describe the landings about to begin in Algeria and Morocco.

Giraud would not be deflected. The plan impressed him, but what about the bridgehead in southern France? He believed twenty armored divisions there should suffice. Were they ready? And was Eisenhower aware that Giraud outranked him, four stars to three? But the heart of the matter was supreme command of any landing on French soil. “Giraud,” he said, “cannot accept less.”

After four hours of this, Eisenhower emerged from what he now called “my dungeon,” his face as crimson as the light over the door. He had agreed to dine in the British admiralty mess while Giraud enjoyed the governor-general’s hospitality at Government House. Several days earlier, Eisenhower had warned Marshall: “The question of overall command is going to be a delicate one…. I will have to ride a rather slippery rail on this matter, but believe that I can manage it without giving serious offense.” Unfortunately, Clark had ended this first meeting by telling Giraud, “Old gentleman, I hope you know that from now on your ass is out in the snow.” Eisenhower dashed off a quick message to Marshall, closing with the simple confession: “I’m weary.”

Dinner at Government House, where the sherry cask was always full and the larder well provisioned, softened Giraud not a whit. Back in Eisenhower’s office at 10:30

P.M.

, with the red light again burning, he again refused all appeals. After two hours of circular argument, Giraud retired from the field. The impasse remained: Giraud wanted supreme command, not the limited command of French troops offered by the Americans. His favorite joke was that generals rose early to do nothing all day, while diplomats rose late for the same purpose; tomorrow’s dawn would bring another opportunity for inaction, and he announced plans to shop for underwear and shoes in the town bazaar. Clark threatened him again, although less crudely this time. “We would like the honorable general to know that the time of his usefulness to the Americans for the restoration of the glory that was France is

now,

” he said through the interpreter. “We do not need you after tonight.”

Giraud took his leave with a shrug and a final third-person declaration: “Giraud will be a spectator in this affair.” Eisenhower muttered a sour joke about arranging “a little airplane accident” for their guest, then headed outside for a few moments of meditation.

From the face of the Rock the Mediterranean stretched away to merge with the night sky in a thousand shades of indigo. Eisenhower was a gifted cardplayer and he sensed a bluff. Perhaps Giraud was playing for time, waiting to see how successful the invasion was. Eisenhower suspected he would come around once events had played out a bit.

Otherwise, the news was heartening. After more than two weeks of battle at El Alamein, Rommel was in full retreat from Egypt; the British Eighth Army could either destroy the Afrika Korps piecemeal, or drive Rommel into the

TORCH

forces that would soon occupy Tunisia. And not only had the Axis ambush in the Mediterranean been laid too far east, but a German wolfpack in the Atlantic had been lured away from Morocco by a British merchant convoy sailing from Sierra Leone. More than a dozen cargo ships were sunk, but Hewitt’s transports in Task Force 34 remained unscathed. Was it possible that the great secret would hold until morning? There had been some horrifying security breaches—secret papers, for instance, consigned to a blazing fire at Allied headquarters in London, had been sucked up the chimney, unsinged. Staff officers had scampered across St. James’s Square for an hour, spearing every scrap of white in sight. Still, the Axis forces appeared to have been caught unawares by

TORCH

.

To Marshall, Eisenhower had written: “I do not need to tell you that the past weeks have been a period of strain and anxiety. I think we’ve taken this in our stride…. If a man permitted himself to do so, he could get absolutely frantic about questions of weather, politics, personalities in France and Morocco and so on.”

Eisenhower headed back to his catacomb, dragging on another Camel. He spread his bedroll, determined not to stray from the operations center as he awaited reports from the front. “I fear nothing except bad weather and possibly large losses to submarines,” he had asserted with the bravado of a man obliged by his job to fear everything. Years later, after he was crowned with laurels by the civilized world he had helped save, Eisenhower would remember these hours as the most excruciating of the entire war. In the message to Marshall he had added a poignant postscript.

“To a certain extent,” he wrote, “a man must merely believe in his luck.”

2. L

ANDING

“In the Night, All Cats Are Grey”

T

WO

hundred and thirty nautical miles southeast of Gibraltar, Oran perched above the sea, a splinter of Europe cast onto the African shore. Of the 200,000 residents, three-quarters were European, and the town was believed to have been founded in the tenth century by Moorish merchants from southern Spain. Sacked, rebuilt, and sacked again, Oran eventually found enduring prosperity in piracy; ransom paid for Christian slaves had built the Grand Mosque. Even with its corsairs long gone, the seaport remained, after Algiers, the greatest on the old Pirate Coast. Immense barrels of red wine and tangerine crates by the thousands awaited export on the docks, where white letters painted on a jetty proclaimed Marshal Pétain’s inane slogan:

“Travail, Famille, Patrie.”

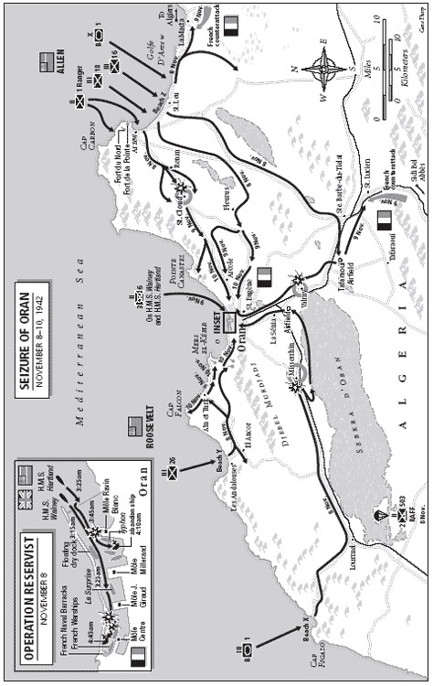

A greasy, swashbuckling ambience pervaded the port’s many grogshops. Quays and breakwaters shaped the busy harbor into a narrow rectangle 1½ miles long, overwatched by forts and shore batteries that swept the sea to the horizon and made Oran among the most ferociously defended ports in the Mediterranean.

Here the Allies had chosen to begin their invasion of North Africa, with a frontal assault by two flimsy Coast Guard cutters and half an American battalion. While Kent Hewitt’s Task Force 34 approached the Moroccan coast, the fleet from Britain had split. Half had turned toward three invasion beaches around Algiers, while the other half steamed for three beaches around Oran. Since the reaction of French defenders in Africa remained uncertain, in both Morocco and Algeria quick success for the Allies required that the ports be seized to expedite the landing of men and supplies. Oran was considered so vital that Eisenhower personally had approved a proposal to take the docks in a bold coup de main before dawn on November 8, 1942.