An Army at Dawn (77 page)

Authors: Rick Atkinson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #War, #bought-and-paid-for

No matter. Montgomery had regained his vim. At 4:30

A.M.

on March 23, he alerted the New Zealand Corps to a complete change of plans. Rather than serve as a sideshow, the Kiwis would deliver the main blow. Three divisions under General Leese would remain on the coast to occupy enemy defenders at Mareth. But reinforcements would add weight to the New Zealand attack, and Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, who had waited in vain with his X Corps to crash through a Leese-made hole at Mareth, would assume command of this new, left-hook assault, code-named

SUPERCHARGE II

. “Am sending Horrocks to take charge,” Montgomery added in his predawn message. “Am sure you will understand.”

One man who did not understand was the New Zealanders’ legendary commander, Lieutenant General Bernard C. Freyberg. English-born but raised in New Zealand, Freyberg had been a dentist before finding his true calling as warrior of Homeric strength and courage. Known as Tiny to his troops, he had a skull the size of a medicine ball, with a pushbroom mustache and legs that extended like sycamore trunks from his khaki shorts. In the Great War, he had won the Victoria Cross on the Somme, served as a pallbearer for his great friend Rupert Brooke, and emerged so seamed by shrapnel that when Churchill once persuaded him to display his wounds the count reached twenty-seven. More were to come. Oarsman, boxer, swimmer of the English Channel, he had been medically retired for “aortic incompetence” in the 1930s before being summoned back to uniform. No greater heart beat in British battle dress. Churchill a month earlier had proclaimed Freyberg “the salamander of the British empire,” an accolade that raised Kiwi hackles—“Wha’ in ’ell’s a ‘sallymander’?”—until the happy news spread that the creature mythically could pass through fire unharmed. “Simple as a child and as cunning as a Maori dog,” Freyberg was both superstitious—he refused, for example, to look at a new moon through glass—and literate. In his raspy voice he enjoyed reciting Mrs. Bennet’s gleeful prattle in

Pride and Prejudice

upon learning that her daughter Lizzy is to marry the rich Mr. Darcy: “Ten thousand a year! Oh, Lord! What will become of me? I shall go distracted!”

The Salamander was displeased at being supplanted by Horrocks, who was six years younger as well as junior in grade. Freyberg seemed “grim, firm, and not at all forthcoming,” the British official history recorded, while Horrocks “felt embarrassed and was annoyed too.” Montgomery sought to make amends for his offense by sending each man a bottle of brandy, while De Guingand addressed all messages to “my dear Generals” and jokingly referred to them as “Hindenburg and Ludendorff.”

Montgomery set aside thoughts of Tunis and Sicily long enough to concoct a plan worthy of his reputation. Insisting that

SUPERCHARGE II

go forward as quickly as possible, he also proposed an unusual late-afternoon attack out of the southwest: at that hour, the sinking sun would blind Axis defenders. After a frantically busy night of creeping forward and digging in, by dawn on March 26 some 40,000 attackers and 250 tanks lay hidden near an old Roman wall that stretched four miles across Tebaga Gap. From their camouflaged holes, the men watched the sun march across the African sky until it was directly behind them. Officers played chess in their slit trenches to while away the hours.

Then, at 3:30

P.M.

, low waves of British and American bombers attacked Axis targets marked with red and blue artillery smoke shells. Thirty minutes later, the Royal Artillery erupted in a thundering cannonade as a providential sandstorm further blinded the defenders. At precisely 4:15

P.M.

the first tanks surged from their revetments, with shrieking Maori riflemen clinging to their hulls. One Kiwi commander recounted:

The infantry climbed out of their pits—where there had been nothing visible there were now hundreds of men who shook out into long lines and followed on five hundred yards behind the tanks. At 4:23

P.M.

the barrage lifted a hundred yards—an extraordinary level line of bursting shells—tanks and infantry closed to it, and the assault was on.

Through the gap they poured, the forward edge of the advancing ranks marked with swirling orange smoke for the benefit of Allied pilots. “Speed up, straight through, no halting,” officers called. Two German battalions buckled and collapsed. On one particularly bloody hill, a brigadier reported “dead and mangled Germans everywhere, more than I had seen in a small area since the Somme in 1916.” British tank commanders heaved grenades from their open hatches and Maoris pelted the fleeing enemy troops with stones when their ammunition ran out. To the east, Gurkhas from the 4th Indian Division went baying into battle “not unlike hounds finding the scent.”

By nightfall, the attack had penetrated four miles into the pass. Tanks “trundled as snails feeling their way” in the darkness until midnight, when the rising moon emerged from the clouds to reveal the extraordinary spectacle of British and German forces hurrying side by side toward the vital road junction of El Hamma at the head of Tebaga Gap.

It was a race the Germans won, if only temporarily. In the early morning of March 27 an improvised antitank screen of eleven guns—as crudely effective as a dropped portcullis—delayed the British for more than a day three miles south of El Hamma. That was long enough. By the time the blockade was flanked, General Messe had adroitly pulled back his forces from both Mareth and Tebaga Gap toward another fortified gap at Wadi Akarit, sixty miles north. “Like a black snake squirming over the ground we could see the lorries and guns of the German tail making their escape,” a disappointed British soldier reported. “Once again…a clever escape.”

Montgomery had won a battle but not a resounding victory, and certainly not the war. Three German divisions, with the help of Italian cannon fodder, had thwarted three British corps for a fortnight. True, the price was dear, and this Axis army could hardly afford heavy casualties. Seven thousand Axis prisoners were taken in the Mareth actions, a third of them German; the cost to Eighth Army totaled 4,000, including 600 casualties in the breakthrough at Tebaga Gap. After the battle a single British private was seen leading several hundred Italian prisoners, who chattered like parrots; asked if he needed help escorting them to their cages, the young soldier answered, “Oh, Lord, no! They trust me.”

“It was the most enjoyable battle I have ever fought,” Montgomery exulted. Perhaps so, although local legend attributed the severe five-year drought that began in 1943 to Montgomery’s imprecations on the land. Yet Eighth Army had forced the outer gate to begin its inexorable march up Tunisia’s east coast toward Tunis. That was plain, and every sensible German and Italian officer knew that the two Axis armies now faced mortal peril from the two Allied armies.

Yet Eighth Army still seemed to lack an instinct for the jugular. In boxing terms, it was a poor finisher. General Freyberg ordered his advance squadrons to bypass Gabès on the morning of March 29 and give chase on the coastal road—ordered this only to learn that at that very moment the spearhead commander was accepting the keys to the city from the Gabès mayor. The 4th Indian Division, already delayed a critical twelve hours by a horrendous traffic jam, was forced to wait at Gabès while the 51st Highlanders donned their kilts for a proper march-through with pipers. Again pursuit languished. “The enemy does not follow,” the 90th Light Division war diary noted. The retreating Axis soldiers had time to pilfer tables, mirrors, women’s dresses, even pianos. The British had to settle for six captured railcars full of German sausage.

Some of Montgomery’s admirers considered his mid-battle switch from a frontal assault to the sweeping left hook among the boldest decisions in his glorious career. Yet a more imaginative plan at the outset, enforced by a more attentive commander, might have made Mareth the decisive battle it could have been. “We never lost the initiative, and we made the enemy dance to our tune the whole time,” Montgomery claimed on March 31. That assertion was questionable. He had violated his own wise precept “to concentrate all your forces and give a mighty crack.” He also had underestimated the resourcefulness of his enemy; the technical requirements of fighting in hill country; and the difficulty of crossing a stoutly defended watercourse, the Zigzaou. That boded ill for Eighth Army after years in the desert: the army and its commander would encounter more hills in northern Tunisia and

many

more in Italy, along with innumerable rivers. Major General Francis Tuker, the 4th Indian Division commander, concluded, “There was, in Eighth Army, an apparent lack of purpose at this time.”

In the months after Mareth, Montgomery acknowledged that the failure of his coastal attack had required him to recast his entire plan. There was no shame in deft improvisation, to be sure. But soon he was asserting that the left wing had always been designated to deliver the fatal blow. By the end of the war he even seemed to believe it, having perhaps persuaded himself through repetition. Perhaps the high bar of infallibility demanded no miscues, no false starts, no desperate two

A.M.

wailing about what to do now. As they cleared Gabès for the long, last march toward Tunis, his men gathered themselves for the sort of war—one with mountains and rivers and allies—that would confront them for the duration.

11. O

VER THE

T

OP

“Give Them Some Steel!”

A

N

old Arab song warned:

Gafsa is miserable,

Its water is blood,

Its air is poison.

You may live there a hundred years

Without making a friend.

Miserable it was, a flyspecked phosphate camp of 10,000 souls. Jugurtha, who led the Numidian revolt against Rome in the second century

B.C.

, once hid his treasury here because the town was so remote. After changing hands four times in the past three months, Gafsa had become even more wretched; the budding groves of pomegranates and apricots could hardly redeem the misery of war. As Montgomery prepared to give battle 120 miles southeast at Mareth, General Alexander had ordered the Americans to liberate Gafsa yet again. The attack was code-named Operation

WOP

, in homage to the 7,000 Centauro Division soldiers occupying the town and nearby hills. GIs composed their own tribute, a ribald ditty titled “The Third Time We Took Gafsa.”

If seizing Gafsa seemed insufficiently ambitious for Patton’s II Corps, which had swelled to 88,473 men—precisely the size of Sherman’s army in Carolina at the end of the Civil War—the modesty of the assignment reflected Alexander’s disdain for American fighting prowess. Alexander had two strategic options. He could use II Corps and Anderson’s First Army to drive a wedge between the Axis forces across the Eastern Dorsal, isolating Arnim’s army in the north from the First Italian Army in the south; each would in turn be ground between the Allied millstones. Or, he could squeeze Axis troops into a shrinking bridgehead around Tunis, with Montgomery’s Eighth Army crushing the enemy to pulp.

Alexander chose the latter course. The inexperienced Americans, he believed, could not withstand the panzer counterattacks sure to follow any attempt to split the bridgehead. “I do

not

want the Americans getting in the way,” Montgomery privately told Alexander. Instead, he added, the cousins should “get the road ready for me to use” by lifting mines and fixing potholes.

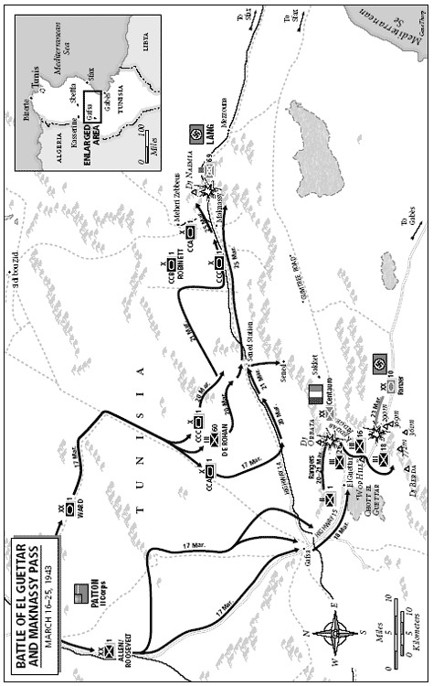

Montgomery was insufferable, as usual, but Alexander’s decision was defensible in the wake of Kasserine: the memory of terrified Yanks scorching up the Thala road remained vivid. With Eisenhower’s concurrence, he twice warned Patton to avoid “pitched, indecisive battles” where “we might get into trouble.” Alexander considered Patton “a dashing steed,” but he did not want him dashing into Montgomery’s path. Patton would be kept on a tighter rein than Montgomery and even Anderson. Allen’s 1st Division was ordered to “assist the advance of the British Eighth Army from the south” by building a supply dump in Gafsa and protecting Montgomery’s left flank as he drove toward Sfax and then Tunis. Only scouts would venture southeast of Gafsa toward Gabès, although if things went well Ward’s 1st Armored Division might later push on due east through Sened Station to Maknassy. Of Patton’s four divisions, the greenest pair—the 34th and 9th—would remain in reserve.

Patton was incensed at being relegated to a weak supporting role, but he swallowed his pride and prepared to attack. Word of his third star had arrived on March 12. “I am a lieutenant general,” he told his diary. “Now I want, and will get, four stars.” A day later, as if recalculating the azimuth of his character, he added, “I am just the same since I am a lieutenant general.” No man felt a more vivid kinship with the great captains of yore, and Patton now likened the Gafsa offensive to Stonewall Jackson’s flank attack in support of Longstreet at the Second Battle of Manassas in 1862. Tromping about in high brown boots and a fleece-lined coat, he told his commanders he wanted “to see more dead bodies, American as well as German.” To his troops he declaimed: