An Evil Spirit Out of the West (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) (17 page)

Read An Evil Spirit Out of the West (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) Online

Authors: Paul Doherty

Chapter 7

In the freezing cold dark of the desert we buried the stiffening corpses of the Kushites. Snefru informed me that the corpses of the others had been similarly concealed. We dug deep in the hot sand. Afterwards the Veiled One gathered us together.

‘What you have done,’ he declared gently, as if addressing a group of friends, ‘has been ordained and is fitting punishment for traitors. No one lifts his hand against the Son of the Divine One. You are now to return.’ He gazed round, peering at them through the dark as if memorising the faces of this group. ‘Go back to the palace but return individually. Should anyone ask, you know nothing of this. Indeed, for time immemorial, you shall know nothing of this.’

Once they were gone, padding away through the night, the Veiled One took a brand from the fire and burned his pavilion. Then, taking his sword, he hacked at the chariot like a man possessed, denting its finery, shattering the decorations, splintering the javelin holder and damaging the quiver. The splendid Bow of Honour, his favourite weapon for the hunt, was also gouged and marked. Javelins and arrows were thrown onto the sand. Bereft of his cane, his ungainly movements assumed a menace all of their own. I was not invited to join him; he acted like a man demented. When he stopped, he stood, arms drooping, eyes glazed, chest heaving with exertion. He fell to his knees and threw sand over his face. Then, he drew his dagger, lurched to his feet and staggered towards me. He looked as if he was going to trip. I went forward to help but he moved quickly, his arm coming up, the knife slicing my upper arm and nicking my left wrist. I flinched in pain and drew away but he followed on, grasping my tunic and tearing it. I made to resist.

‘Mahu, think! We have been attacked by Libyans, Desert Wanderers.’ He fashioned makeshift bandages to staunch the wound then inflicted similar cuts on himself. All around us was darkness, in this haunted place with the roars of the night prowlers drawing closer and the biting wind turning our sweat cold, coating us in a fine dust which stung our eyes. I ached from head to toe. The wounds from the razor-edged knife smarted as if I had been burned with fiery coals. Once satisfied, the Veiled One took another brand from the fire and stared around. He looked eerie in the dancing flames with his long face and awkward body yet his eyes were steady. When he spoke, his voice was soft as if talking to himself or praying, I don’t know which.

‘Come, Baboon, we are finished here.’

We unhobbled the horses, the Veiled One patting them reassuringly: the beasts could smell the blood, and the dark shapes of the night prowlers increased their alarm. We climbed into the chariot and were gone, out of that ghost-filled gully, hooves pounding, wheels rattling as we fled like birds of ill omen under a starlit sky back to our quarters in the Malkata Palace.

Snefru and the others acted as if nothing untoward had happened. Naturally, of course, the Veiled One’s appearance without his Kushite guards, the state of both ourselves and the chariot raised uproar and alarm. Messengers were despatched to the palace. I assisted the Veiled One to his quarters, helped him strip, wash and don new robes. He did the same for me as if we were two boys desperate to escape the effects of our mischief. Royal physicians arrived. They questioned my master, scrupulously searched for any injury, then they turned on me. We both acted our roles and sang the same hymn: how we had gone out into the Eastern Desert to hunt and been ambushed by Libyan Desert Wanderers. The Veiled One acted all mournful, as did I. He described how his Kushite guard had put up a brave fight. Some were killed, others probably captured whilst, as the Veiled One hinted, the remainder may even have deserted.

Of course, no one could disprove our story. Great Queen Tiye, accompanied by the Crown Prince Tuthmosis, soon arrived. This time the Queen came in all her haughty beauty, garbed in costly robes, gold sandals with silver thongs, and a bejewelled head-dress. Crown Prince Tuthmosis looked more anxious than his mother. He was pale, rather thin from the loss of body fat. He ignored me and remained closeted with his mother and brother. At the end of their meeting Queen Tiye demanded to see me alone in the hall of audience. Tuthmosis had been sent to guard the door. The Queen acted her part, all anxious-eyed, a little nervous, solicitous and grateful that we had escaped – though I could tell from the amusement in her eyes that she knew what had truly happened.

‘I am concerned,’ her voice rose, eyes full of mockery, ‘I am concerned at my son’s security.’

‘Excellency,’ I replied, kneeling before her, ‘I have already taken care of that. I have armed a number of the Rhinoceri servants. Many of them have seen military service. I believe your son, my master, thinks that security enough.’

We spoke one thing with our mouths and another with our eyes. Tuthmosis, however, was not so easily mollified. He came striding down the hall, coughing into his hands. When he stopped before me, I saw the piece of linen furtively thrust up the voluminous sleeve, pushed under a wrist strap which dangled rather loosely.

‘Mother, guards should be brought from the palace!’

‘Yes and no,’ Tiye replied. ‘My son is disturbed. I think it’s best if he feels secure, for the moment at least.’

They left shortly afterwards. The Veiled One summoned me to his quarters. He was sitting cross-legged on his bed staring out of the open window and watching the sun set.

‘All life comes from him, Mahu. He who dwells on all things and supports all things. The One who numbers our days and metes out judgement. I am his Beloved.’ He looked over his shoulder at me and rubbed a finger up and down that long nose, his lower lip jutting out. ‘All life is sacred, Mahu. Be it a bird on the wing or a fish in the river.’

‘And the Kushites we slaughtered?’ I asked.

‘They died because their lives were not sacred any more.’ He turned to gaze out of the window. ‘What will happen to us, Mahu? We are like children, being chased by shadows. We can turn and hide and fight, but still the chase goes on. My father will send other soldiers or a gift, some tainted wine or poisoned food. What will happen, Mahu?’

I knelt down. It was the first time the Veiled One had ever really asked me a question. The tone of his voice revealed that he was waiting for an answer. I don’t know what prompted my reply but the words came tumbling out before I could even reflect on them.

‘He has commanded you, his son, to appear

rich and magnificent.

He has united with your beauty.

He will hand over to you his daily plans.

You are his eldest son who came into existence

through him.

Hail to you, the One who is splendid in skills!

You have come from the Horizon of the sky!

You are beautiful and young like the Aten.

‘You will become,’ I continued in a rush, ‘Lord of the Two Lands, Holder of the Diadem, he who speaks with true voice, whose heel will rest on the neck of the People of the Nine Bows.’

The Veiled One lifted his hands. He was staring fixedly at the setting sun. Then he clambered off the bed and came towards me. I kept my head bowed, staring at those strange feet with their elongated toes and bony ankles. He stopped, grasped me by the hand and pulled me to my feet, his face wreathed in smiles, his eyes bright with life. He placed a hand on each of my shoulders and stared at me as if he was seeing me for the first time. Then he clasped me to him. I could feel the bones of his pigeon chest, the strength of those long arms; I could smell the perfume on his flesh.

‘Blessed are you, Mahu,’ he whispered, ‘least yet first amongst men. It is not flesh and blood which has revealed this to you but my Father who dwells beyond the Far Horizon and whose fingers have touched your heart so that you speak with true voice. Blessed are you, Mahu, son of Seostris, friend of Pharaoh.’

He released his grip and stood back. Hobbling over to a side table, he removed the cloth from a jug and filled two goblets of wine, serving me mine as if I was a priest in a temple.

‘Do you know what you said? Do you recognise the truth of my reply?’

In fact, I didn’t. On reflection what had prompted me was Tuthmosis, pale and narrow-faced, that blood-speckled napkin being thrust up his sleeve, and this enigmatic ungainly young man who could sing a song to a butterfly but kill like any panther from the South. We drank the wine and the Veiled One, drawing me close, whispered what I was to do. From that evening on I became responsible for his safety and security. Snefru, still nervous after the killing in the desert, became Captain of his guard.

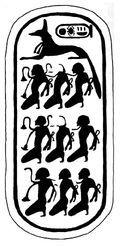

The following morning a cart arrived, a gift from Queen Tiye, not food or drink or precious robes but the finest weapons and armour from the imperial storerooms. I gave Snefru two tasks: to train his men and recruit others who could be trusted, and to hire more servants from the village of the Rhinoceri. The Veiled One had a hand in this. He gave each of his new bodyguards an amulet, a scarab depicting the Aten, the Sun in Glory, rising between the Two Peaks in the East. He made them kneel in the dust of the courtyard, as he passed from one to another, gently asking their names, thrusting the insignia of office into their hands and softly caressing the head of each man. I was not so gentle but gave them a lecture Weni and Colonel Perra would have been proud of: their loyalty was to me and to their Prince. They were guarantors of each other’s fidelity. The treachery of one was the treachery of all and the good of their Prince was the glory of all. I then distributed the weapons, the leather kilts, the shields and spears, organising a roster of duties, interviewing each new recruit, accepting some, rejecting others.

The walls and gates of the Silent Pavilion were now closely guarded. No one arrived or left without my knowing; even the servants who went down to the marketplace were watched carefully. To all appearances the Veiled One’s household was depleted, disorganised. The Prince, our master, was sheltering in his chamber after the hideous incidents out in the Eastern Desert. The truth was very different. Security was the order of the day, the protection of the Prince our constant watchword. Food and wine were rigorously checked. A servant girl who could not explain why she had left the market in Thebes to visit the Temple of Isis quietly disappeared. At the same time the Prince opened his treasures. The Kushites had been paid from the House of Silver; now every one of his bodyguards was lavishly rewarded by the One they served. Of course God’s Father Hotep came sauntering into my master’s residence, walking through the gates, escorted by a gaggle of priests and officers from the Sacred Band. I quickly recognised the faces of Horemheb and Rameses: burned dark by the sun, garbed in their dress armour, they moved with all the swagger and arrogance of their kind. I met Hotep at the gates to the Prince’s garden.

‘I bring a request from my master,’ I whispered, bowing low. ‘He asks that your retainers’ – I heard a gasp of anger from some of the officers – ‘

your retainers

,’ I repeated, ‘either stay in the courtyard,’ I gestured round, ‘where there is shade, and where food and wine will be brought, or perhaps beneath the trees beyond the gates.’

your retainers

,’ I repeated, ‘either stay in the courtyard,’ I gestured round, ‘where there is shade, and where food and wine will be brought, or perhaps beneath the trees beyond the gates.’

Hotep held my gaze, those bright, sardonic eyes studying me carefully.

‘So you do not wish my companions to be wandering about?’

‘Excellency,’ I bowed again, ‘you and yours are most welcome here. However, you must remember, the Prince has lost the Captain of his guard – that vile attack in the Eastern Red Lands …’ I spread my hands. ‘My master is not a warrior or soldier …’ My voice faltered as if I, too, was nervous. Hotep turned, fanning his face, and gazed round, noting the guards at every doorway, spears at the ready, archers with their bows unslung. He grinned lazily at me and tapped me on the chest.

‘Horemheb is right. You are a clever baboon.’ He turned to his retainers. ‘Gentlemen, you may stay here. I bear messages from the Divine One.’

And, brushing by me, he entered the garden where my master was waiting for him in the pavilion. His escort rather self-consciously broke up. Some drifted towards the gate or made for the shade of the trees. Horemheb and Rameses, gold collars gleaming in the sun, remained standing alone, tapping their staffs of office against their legs.

‘My friends!’ I exchanged the kiss of peace with each of them.

Rameses pinched my arm mischievously.

‘You’ve climbed high, Baboon,’ he whispered before letting me go, so I could clasp Horemheb’s hand. The great soldier had filled out, muscular in his shoulders and arms, strong of grip, dark eyes in that hard, granite-like face. Both he and Rameses had their heads completely shaven. Horemheb had a scar high on his right cheekbone. He noted my gaze and rubbed this.

‘A Libyan arrow.’ His mouth smiled but his eyes didn’t. ‘Brother Rameses and I have been out in the Eastern Desert pursuing these marauders who attacked your master.’

‘We found some javelins and arrows, bones whitening under the sun.’ Horemheb squinted up at the sky. ‘As mine will if we don’t get into the shade and have some wine.’

I ushered them into the house, to the small tables I had prepared in an alcove beneath a window which overlooked the garden. I served them sweet white wine and a dish of glazed walnuts smeared with honey on strips of flat bread. They both ate, noisily smacking their lips, dabbing their fingers in the water bowl and wiping them on the napkins as they stared around. Horemheb noticed the guards standing in the shadows and grinned.

‘How good are they, Mahu?’ he asked, nodding his head. ‘As skilled as the Kushites?’

‘They are loyal and they will kill.’ I smiled and toasted him with my cup.

Rameses laughed behind his hand. ‘Soldiers with no noses,’ he taunted, ‘and little military training. Have they been drilled by you, Mahu?’

‘Tell me,’ I replied, ignoring his question, ‘what do men fight for the most? For money? Plunder? Women?’

‘Glory,’ Horemheb snapped. ‘The glory of To-mery, the Kingdom of Egypt.’

‘What about their own glory,’ I retorted, ‘as well as that of the One they serve?’

The smile faded from Horemheb’s face. ‘The Divine One could send the regiment here,’ he whispered, ‘and soon take care of these toy soldiers.’

‘Attack his own son?’ I replied. ‘Queen Tiye’s beloved? My friends, I shall tell you something: there are moments in life when you make choices. On these choices your life, your fame, your fortune depend.’

‘What are you saying?’ Rameses snarled, his lean face ugly with the anger seething within him.

‘We are children of the Kap,’ I replied. ‘I am not threatening you, or describing the way things should be, just the way they are. I gave Sobeck good advice and he ignored it. I did what I could for him. Don’t you expect me to do the same for you?’

Horemheb wiped his mouth on the back of his hand and got to his feet. Rameses followed. He was about to walk away when he came back and smiled down at me.

‘I’ve got two new dwarves,’ he said. ‘I never forgot that night, Mahu,’ his smile widened, ‘and the horrors of the crocodile pool. You are right. You never know when you can be swept away.’

He and Rameses sauntered lazily to the door. They’d hardly gone when Hotep appeared. He gestured at me not to rise and sat down opposite.

‘Well, well, well.’ His furrowed face broke into a smile, eyes watchful, like a hawk on its perch. ‘Quite a few changes here, Mahu.’

‘It is important that the Prince feels secure.’

‘He’s under the care of the Divine One; we all rest in the shadow of his hands.’

‘Of course,’ I replied. ‘Still, prudence and wisdom are gifts of the gods.’

Hotep picked up Horemheb’s cup and sipped at it. ‘Tell me again what happened in the Red Lands.’

I did so. Hotep sat nodding his head. ‘And Imri?’

I gave him a description of our calamitous journey on the river. ‘An unfortunate accident,’ I concluded.

‘And all of Imri’s guard were killed out in the Red Lands?’

‘So it would seem.’

‘And you went hunting there?’

‘We went hunting,’ I replied, holding his gaze. ‘Gazelle and ostrich, whatever crossed our path.’

‘But you never took Saluki hounds?’

I hid my disquiet – a mistake we had overlooked.

Hotep put the cup down. ‘Why didn’t you take Saluki hounds? They are as fleet as any deer.’

‘My master knows my dislike of Saluki hounds,’ I replied quietly. ‘My Aunt Isithia had one called Seth. He killed my pet monkey – I never forgot.’

‘Ah yes, Isithia.’ Hotep scratched his neck. ‘I understand you don’t visit her.’

‘She is never far from my heart.’

Hotep smiled thinly. ‘She said that your fates were intertwined.’

A prickle of fear curled along my back. ‘Whose fates, Excellency?’

Hotep sipped from his cup to conceal his own disquiet.

‘Why was I sent to the Kap?’ I asked abruptly. ‘My father was a brave soldier but Thebes is full of the sons of brave soldiers.’

‘Your aunt petitioned me whilst your father’s bravery was known to the Divine One, but that’s in the past, Mahu.’ Hotep smiled. ‘The evils of one day are enough and we must look to the future. What will happen to your Prince when his brother succeeds?’

‘May Pharaoh live for a million years,’ I replied.

‘Of course,’ Hotep agreed, ‘and enjoy a thousand jubilees. My question still stands. You talk of choices.’

‘When did I talk of choices?’

Again the crooked smile.

‘Don’t you know, Mahu? Even the breeze can carry words. You must make choices.’ Hotep spread his hands. ‘Which path you are going to follow? Whom will you truly serve? Ah well.’ He brushed some crumbs from his robe and got to his feet. ‘I don’t want your answer now, but one day.’ He plucked a fan from his sleeve to cool his face. ‘You know where I am.’ He turned away but then came back. ‘Your master, he talks to you?’

‘Like my aunt talked to her Saluki hound.’

Hotep smacked me across the face with his fan. ‘What do you think of your master, Mahu?’

‘I don’t think at all about him, Excellency. I do meditate quite often, at the way things are and, perhaps, the way things should be. I remember the poet’s words. You may know the line? “It is easier to hate than to love. It is better to love than to hate. But sometimes, you must hate to protect what you love”.’

‘A riddle?’ Hotep stepped back.

‘The solution is easy, Excellency. I could take an example from agriculture. They say that you are the son of a farmer?’

‘And?’

‘As the vine is planted,’ I replied, ‘so shall it grow.’

‘Are you talking about yourself?’ he queried.

‘No, Excellency, I am talking about all of us.’

I have been asked where it really all started, when I became aware of the real cause. I have been asked to speak with true voice. I do find this difficult. It’s like a fire in a house. You smell the smoke, you see the wisps but you are not certain where the fire is burning. So it is with the one they now call the Accursed, Akhenaten, the Grotesque, the Ugly One, the Veiled One, the Beloved of the Aten, the Lord of the Diadems.

I suppose it all began the night after Hotep had left. They came for me when the darkness was deepest, sliding into my chamber, stifling my mouth, binding my hands and feet, wrapping me in a coarse blanket. I struggled, lashed out, but they carried me effortlessly, moving like shadows along the passageway down the stairs and across the courtyard. A cold breeze pierced the blanket and froze my sweat. A gate opened. The smell of wood, of flowers, of crushed grass; more voices talking swiftly, hoarsely indistinct. Orders were being issued.

I was thrown into a cart which moved; every jolt of its wheels felt like a blow. This time there were different smells, the sounds of the night, the screech of an animal in pain, the cry of a bird. The breeze grew colder; I heard the slop of water. I was being taken aboard a barge. My terrors increased. Images came and went of the Danga dwarf being swept towards the crocodile pool, of Imri fighting for his life. Who were my abductors? Had the Veiled One changed his mind? Had Hotep taken matters into his own hands? Or had the Magnificent One, tired of his wife’s intervention, despatched his assassins?

Other books

Wolf to the Slaughter by Ruth Rendell

Hellstrom's Hive by Frank Herbert

Cleopatra Occult by Swanson, Peter Joseph

Penelope's Punishment by Zoe Blake

By the Time You Read This by Giles Blunt

Act of Darkness by Jane Haddam

Island Getaway, An Art Crime Team Mystery by Jenna Bennett

RIFT (The Rift Saga Book 1) by Andreas Christensen

A Breath of Scandal by Connie Mason

Witching Moon by Rebecca York