An Evil Spirit Out of the West (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) (48 page)

Read An Evil Spirit Out of the West (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) Online

Authors: Paul Doherty

‘They were not the Sekhmets,’ I protested. I paced up and down his palatial chapel. ‘They have been conspirators, they may have had malice in their hearts. Only the gods know …’

‘Pardon?’ Ay called out.

I beat my breast. ‘Only the One who sees all things truly knew what was in their hearts, but I do not think they were the Sekhmets.’

‘Why not?’

‘They were too clumsy, too easy to discover. Moreover, they had spent most of their lives in Thebes, yet we know from police reports that the Sekhmets have been busy in Memphis and Abydos.’

‘They lied,’ Ay countered. ‘Assassins always lie to protect themselves. Mahu, be content. Pharaoh has smiled on you. You have won Pharaoh’s favour. The task he assigned you is now finished.’

I stared at that cunning face, those eyes which betrayed nothing. Was it Ay who’d hired the Sekhmets? Was that why he was so eager to pass the blame onto the scribe priests? Ay with his genius for questioning, for weighing everything carefully in his own dark heart. Why had he been so quick to point the finger of accusation? I bowed, quickly left and returned to my searches. I had almost given up hope, decided to let matters be and dismiss Sobeck’s report as idle babble, rootless chatter when, one night, Djarka let slip a remark which made my heart skip a beat. I’d stumbled, quite unexpectedly, on the identity of the Sekhmets.

Chapter 18Horemheb and Rameses hunted Amun and all his followers in the temples and along the avenues and streets of Thebes: not even private tombs were safe. I quietly laughed at the stories of how Akhenaten’s agents broke the seals of sepulchres and went in to wipe out the picture of a goose, sacred to Amun, from paintings on the wall. In the City of the Aten Meryre and the rest of the toadies, those sanctimonious hypocrites, rose to the occasion only too eager to prove their subservience and unquestioned loyalty. Houses, shops and warehouses were raided, statuettes of any other god seized and destroyed. Those who had offended the majesty of the Aten were publicly ridiculed, being placed on donkeys, their faces towards the tails and paraded through the streets. It was now a crime in the City of the Aten to praise the wrong god, to honour some other deity. A growing restlessness manifested itself, not helped by shooting stars scrawling the heavens at night and heartchilling rumours about a hideous pestilence which had broken out across Sinai.

I continued my hunt for the Sekhmets. One question still puzzled me. I knew who they were and had a hardening suspicion about who had hired them. I had reached the conclusion that they worked for one person and one person alone, so how had Sobeck’s spies come to know that someone was searching for the Sekhmets along the alleyways and the streets of Thebes? Maybe the person responsible for the assassins had deliberately spread the rumour about Sekhmets being hired in order to lay the blame at the door of Amun – which Akhenaten had been only too happy to accept. I dared not trust any of my agents or spies, nor could I inform Djarka, so I went out at night to watch the house myself.

My long vigil proved my suspicions were correct. So, when Makhre and Nekmet invited Djarka and myself to a sumptuous meal of clover and fish served in a special sauce, I eagerly accepted. Their eating-house had been closed for the evening, and Makhre and Nekmet acted as both our hosts and servants. We ate on the flat roof of the house overlooking an elegant courtyard. A small fountain splashed and countless flower baskets sent up their own fragrance to mingle with the sweetness from the pots of frankincense and cassia arranged in the shadow of the parapet along the roof terrace. The meats were delicious, the sauce fresh and tasty to the palate, the bread sweet and soft, laced with carob seeds and a dash of honey whilst the wine was the richest from the black soil of Canaan. It was a beautiful evening with the sky changing colour and, as the sun set, the eastern cliffs dazzled in its dying rays. I was careful of what I ate and drank as I studied this precious pair: Makhre in his white robes, head and face gleaming with perfumed oil, Nekmet soft-skinned and doe-eyed, resplendent in her pleated robes and delicate jewellery. Even then I was arrogant; I did not know the full truth, the hideous secret which would eventually bring so many dreams crashing down. At that moment in time I was only concerned with Djarka and his love for this elegant young woman. Eventually I decided to confront her. As Nekmet served me a dish of lettuce garnished with oil and herbs, Djarka was teasing her about flirting with me. Makhre was laughing. I could take no more. Instead of accepting the bowl I grasped her wrist so tightly she winced.

‘You are from Akhmin?’

‘No, we’re not,’ Makhre scoffed but his eyes became watchful.

‘But you told Djarka the other day that you were?’

‘What?’ Makhre turned to his daughter. She shook her head.

‘But you did.’ Djarka, now alarmed, cradled his cup, not knowing who to stare at. I let go of Nekmet’s hand.

‘You are from Akhmin,’ I repeated. ‘You told Djarka, Nekmet, that you were born there. I am sure it was a slip. If you were there, so were your mother and father. So why do you lie now?’

The banquet was over. Makhre and Nekmet’s faces betrayed them. For the first time ever they had been confronted with their true identity.

‘You are from Akhmin,’ I repeated. ‘For all I know you may well be related to God’s Father Ay, close friend of Pharaoh. So why do you come wandering into the City of the Aten as if you know no one? Why do you have to cultivate my lieutenant Djarka? Gain an entry to the palace when God’s Father Ay could have achieved that with a nod of his head?’

‘You are mistaken,’ Makhre flustered. ‘My lord Mahu, you are truly mistaken. I do not know God’s Father Ay. I have seen him from afar. I …’

‘You are a liar! You do not speak with true voice because you do not know the truth.’

‘Mahu!’ Djarka warned.

‘I have watched this house myself. Late at night I have seen God’s Father Ay slip in and out. So, why are you here, Makhre and Nekmet? Whom are you hunting? Me? Djarka? Or the Divine One himself?’

Nekmet picked up a slice of pomegranate. She chewed on it carefully, using this to glance sideways at her father.

‘You call yourself the Sekhmets,’ I continued. ‘A family of assassins. You come from Akhmin. You work for one person only, the lord Ay. Years ago, Makhre, it was you and your wife, but she died. Now it’s you and your beautiful daughter. You slaughtered certain people in Thebes just before the Divine One left that city. You advertised your slayings so people thought that it was business rivals or enemies settling grudges. However, all your victims in Thebes had one thing in common: they were enemies of Ay. The same is true of your other prey in the cities along the Nile.’

Some of what I said was true, the rest mere conjecture.

‘You were brought here by lord Ay,’ I continued. ‘We are not your victims but, through us, particularly Djarka, you have gained admission to the palace.’

‘But we’ve been there,’ Nekmet protested. ‘We did no harm!’

‘Of course not.’ I pushed the wine-cup away. ‘A true assassin must first get himself accepted, become part of the normal life, the regular routine. Moreover, there is no hurry. Whoever your victim was, you were not to strike until lord Ay gave you the order.’

‘But do you have proof?’ Makhre had recovered his wits.

‘Don’t sit there and fence with me as if we are children with sticks,’ I snarled. ‘I’ll have this house searched; I am sure I will find what I have to.’

‘And where are your police?’ Nekmet asked.

‘You know full well,’ I retorted, ‘no one else knows. The Divine One thinks the Sekhmets have been apprehended and executed. However, if he discovered the true assassins were patronised, given access to the palace by his own Lieutenant of Police, Djarka would also feel his wrath.’

‘Let us go to see the lord Ay,’ Makhre offered.

‘He’ll deny it,’ I replied. ‘He’ll call me mad or insane, but the damage will be done. He’ll arrange for you to disappear and Djarka will continue to live under the shadow of suspicion.’

‘I really think …’ Makhre pushed the table back. As he made to get up, he flexed his upper arm, so when he struck, I was waiting. The knife secretly clutched in his hand aimed for my throat even as Nekmet lunged at Djarka with a dagger she, too, had concealed. Djarka was faster than I, pushing the table into Nekmet’s stomach, even as Makhre’s knife skimmed the side of my neck. I lunged back with my own knife, cutting and slashing into his exposed throat, dragging the knife round and slicing through the soft part under his chin. He fell back against the cushions, a look of surprise on his face; blood pumping out of his mouth and the jagged gash in his neck. He was shaking like a man with a fever, a hideous sound coming from his lips.

I looked to my right. Djarka had his arm around the back of Nekmet’s head, pushing her even further onto the dagger thrust into her upper belly; her lips were half-open, eyelids fluttering as if she wanted to speak or kiss him. Djarka’s face was a hideous mask, a look of deep pity yet he would not let go of her head or the knife, his eyes only a few inches from hers. Eventually her face went slack, shoulders drooping. Makhre, too, fell quiet, face to one side, his entire chest and groin sopping with blood. I pulled Djarka away, allowing Nekmet’s corpse to fall against the cushions. Then I refilled his cup and my own. While I sat and drank, Djarka sobbed into his hands, one of the most heartwrenching scenes I have ever witnessed. He must have sat for an hour, those two corpses staring at us with their empty, glassy gaze. Birds swooped over the house, the night came, dark and soft as velvet. I kept sipping at the cup. At last Djarka wiped his tears away.

‘Why didn’t you tell me?’ he accused.

In the light of the oil lamps my young friend had aged. His face had lost that olive smoothness, his eyes were red-rimmed; furrows marked either side of his mouth. He had the look of a stricken old man.

‘If I had told you, Djarka, you would not have believed me. I know you. You would have challenged Nekmet. They would have either killed you, lied or fled.’

‘Why?’ Djarka asked. ‘Why did she lie?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘I’ll kill Ay,’ Djarka threatened.

‘No, you won’t.’ I clambered to my feet, my legs tense and hard. ‘Come on, Djarka, we have work to do.’

At first I thought he would refuse but Djarka became impatient to discover more evidence, hoping to prove that I was wrong. Yet he knew the truth. Even as he searched he conceded that Makhre and Nekmet had confessed their own guilt.

‘They would have killed us,’ I declared, ‘and taken our corpses out to the Red Lands.’

We searched that house from cellar to the roof. At first we found nothing except indications that Makhre and his daughter had travelled the length and breadth of the kingdom. They possessed considerable wealth. I went down to the cellar, specially constructed to store wine and other goods which had to be kept cool. The cellar was partitioned by a plaster wall. I examined this carefully, removing the makeshift door. I studied the lintels.

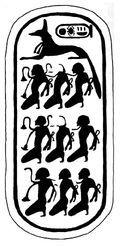

‘This was only meant to be a partition,’ I told Djarka, ‘yet it’s at least a yard wide on either side.’ The dividing wall was of wooden boards covered by a thick plaster; the sides on which the door had been fastened consisted of specially hewn beams. We took these away, and discovered that each side of the partition was, in fact, a narrow secret room. Inside we found our proof: a small coffer with medallions and amulets displaying the lion-headed Sekhmet, Syrian bows, three quivers of arrows, swords, daggers, and writing trays. More importantly, the cache held a carefully contrived and beautifully fashioned medicine chest consisting of jars and pots, all sealed and neatly tagged. We brought these out into the light of the oil lamps.

‘I am no physician,’ I declared, ‘but I suspect these are poisons and potions, enough to kill an entire village.’

We also found documents, all officially sealed, and providing different names and details, as well as pots of paints, wigs, and articles of clothing so Makhre and Nekmet could disguise themselves. Small pouches of gold and silver and a casket of precious stones were also stored there.

Other books

Nevada Heat by Maureen Child

Why Girls Are Weird by Pamela Ribon

Beats of Life (Perception Book 5) by Shandi Boyes

Nothing Like You by Lauren Strasnick

Embrace by Melissa Toppen

Bella's Christmas Bake Off by Sue Watson

Borrowed Dreams (Debbie Macomber Classics) by Macomber, Debbie

The Bear Truth by Ivy Sinclair

Bard's Oath by Joanne Bertin

Two for the Dough by Janet Evanovich