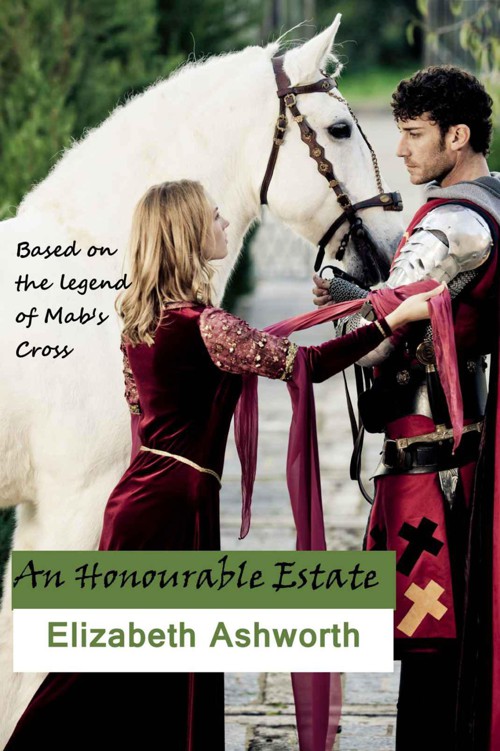

An Honourable Estate

Read An Honourable Estate Online

Authors: Elizabeth Ashworth

An Honourable Estate

Elizabeth Ashworth

Copyright © 2012

Elizabeth Ashworth

Elizabeth Ashworth has

asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be

identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved.

This novel is

based on the legend of Mab’s Cross and is dedicated to the memory of Lady Mabel

de Haigh and Sir William Bradshaw, who can be found lying side by side in Wigan

Parish Church.

Contents

Prologue

1.

Famine

2.

Murder

3.

Rebellion

4. The Sheriff of

Lancaster

5.

A Year and a

Day

6.

The

Outlaw

7.

Dicken

8.

The

Scot

9.

Captive

10. An Audience with the

King

11. The

Adulteress

12. The Battle of

Boroughbridge

13. The

Supplicant

Author’s

Note

Prologue

Mabel

de Haigh paused on the edge of the market place. Her bare feet were

bloodied and torn and the snow-laden wind made her shiver as she limped

forward, bareheaded and dressed only in her linen chemise. In her hand

she shielded a lighted taper, almost burnt down now. The villagers who

lined her path willed her on and gave her strength. Although the penance

for adultery was designed to be a humiliation, these people neither mocked nor

jeered her as she passed, but the men averted their eyes from her unclothed

body and the women whispered words of encouragement and sympathy.

At last she reached the stone cross and knelt before it to

pray to God for the salvation of her soul. She was an adulteress.

She freely admitted her sin to God, priest and man. But she prayed that

God would forgive her as easily as Father Gilbert, her confessor, and the

people of Haigh who stood protectively around her.

“That is enough,” said Father Gilbert as she felt a warm

cloak being placed around her shoulders and the hood raised to cover her hair

which hung loose and unbraided. “Come away now.”

She held up her hand in a silent plea for a few more moments

of prayer. Then she crossed herself, put out the taper and stumbled to

her feet as arms grasped hers and supported her. It was over now and she

could go home, shriven, to have her feet bathed and bandaged and to recover

from her long penitential walk.

Chapter

One

Famine

Bending

over her sewing in the gloom of a single precious candle, Mabel heard the latch

of the outer door click open and William came into the great hall of the manor

house at Haigh. His fair hair was stuck tight to his head and water ran

from it, dripping onto the sackcloth around his shoulders that was supposed to

have kept the rain from his clothes. But when he took it off and shook it

in unison with the dogs who accompanied him, showering Mabel with the droplets,

she saw that the wetness had soaked through to his tunic and that his hose and

boots were similarly sodden and smeared with mud. She sent Edith to fetch

some fresh clothes from the coffer in their bedchamber and cloths for him to

dry himself. Then she called for one of the kitchen boys to bring more

logs to try to kindle the damp wood on the central hearth into a better

blaze. The closed shutters rattled at the windows in a sudden gust of

wind and the incessant rain seeped through and trickled down the white

plastered wall. It was August and it had rained every day for as long as

Mabel could recall.

“Another two dead sheep,” said William as he rubbed his hair,

making the flames of the fire sizzle from the wet drops, “and...” He paused to

look up at her. Even in the gloom she could see the pain in his

eyes. “The blacksmith’s child, the little girl...”

“She died,” said Mabel sadly, knowing what he was going to

tell her from the expression on his face.

“It was not unexpected. You cannot save them all,” he

said in an attempt to comfort her before he returned to rubbing at his hair,

almost standing on the tail of one of the steaming hounds that had spread

itself next to the fire.

The hall filled with the mingling smells of wood smoke, wet

dog, wet wool and dampness. It was a stench that Mabel had come to

associate with the summer of 1315. That and the stench of death as the

animals died in the fields and the children in the village.

She had hoped that the blacksmith’s little daughter could be

saved. She had, with her own hands, prepared an infusion of willow bark

and taken it to the family along with what food she could spare: a loaf of

coarse brown bread, though by the time the grain had been dried in the oven it

contained little nourishment, and, to tempt the child to eat, a tiny portion of

the fresh cod that had come from the weekly market at Wigan. But when she

had looked down at the little girl, no more than bones, lying in her blankets

with her huge blue eyes staring out from her gaunt and colourless face and her

belly swollen despite her hunger, Mabel had known that there was little

hope. The child had had that look of resignation that comes to those on

the brink of death and, despite her prayers and supplications and the lighting

of a precious beeswax candle in the chapel, Mabel was not surprised that God

had seen fit to take her from this world.

“At least her suffering is over,” she said at last, though

they were only words and she knew that she would have to put on her cloak and

pattens and walk down to the small house by the forge to see the frail body and

try to give what solace she could to the parents; to the mother who had tried

to coax some spoonfuls of the medicine into her daughter’s mouth in the hope

that it might work some miracle; and to the father, whose smithy stood silent

and deserted now that there were no animals to shoe or scythes to fashion

because the horses and oxen had died of starvation and the crops stood ruined

in the wet fields.

William ran his fingers through his damp hair and pulled a

rough wooden stool nearer to the blaze, lifting the logs with a long iron poker

to encourage the flames.

“Something will have to be done, Mab,” he said. “We

cannot go on like this. Soon it will be Michaelmas and what will happen

then?” He shrugged his shoulders in a sign of desperation as he stroked

the head of Calab, his favourite dog. “Even if the rain stops there will

be no crop this year but Robert Holland will demand his dues as if the barns

were filled – and neither he nor the Earl of Lancaster will go hungry.”

He threw down the poker in an angry gesture and the dog jerked back his

head. “They have no care if we or our villagers starve.”

“But what can we do?” asked Mabel as she picked up his

discarded towel.

“I could take a deer from the forest and roast it in the

yard.”

“And risk having your hands cut off if you are caught?

Talk sense, William!” she told him. “Besides you know that we owe feudal

allegiance to the earl.”

“That does not mean I have to like him,” said her husband.

William

recalled when he had begun to dislike Thomas, Earl of Lancaster. It had

been three years earlier in the summer of 1312. He had been with the

earl, fulfilling his yearly knight’s service, when the message had come about

Piers Gaveston. That Lancaster hated Gaveston was well known. He

had been the foremost of the earls who had forced the king to send his friend

and companion into exile for a third time and when Lancaster had discovered the

man was back in England he had flown into a rage, kicking stools, dogs and

servants around his lavish hall and vowing revenge on both Gaveston and the

king.

William understood that the Earl of Lancaster had good reason

for his hatred of Gaveston. The Gascon and the king had allegedly sworn

an oath to be blood brothers, a pact that was more often made on the

battlefield or in tournaments, to fight together and to divide the spoils.

But the king had begun to treat Piers Gaveston as if he were truly his familial

brother, giving him precedence over his cousin Lancaster who had been subjected

to more ridicule and taunting from Gaveston than even a peasant could have been

expected to tolerate; and all this from a man only the son of a knight of the

household. Of course it should have been Lancaster who carried the crown

of Edward the Confessor at the king’s coronation, but Gaveston had mocked the

way he walked and laughed that the ceremony would be spoiled by Lancaster’s

minstrel efforts. So Edward had appointed his favourite to the honour

instead. Worse had come when the king was in France with his new bride

Isabella, and Gaveston rather than Lancaster was appointed regent and left in charge

of the kingdom. Even though Lancaster had been ill and unable to fulfil

the role he had still taken offence at the appointment of his sworn enemy and

had sent him a message to say that he would bow down to no one, least of all a

Frenchman.

Gaveston had taken refuge at Scarborough, but the Earl of

Pembroke had persuaded him to give himself up from the besieged castle,

promising him safety if he came out and put himself into his protection to be

escorted to London where parliament would decide his fate. But Pembroke

had been lax. As the party rode south he had not been able to resist the

temptation of a conjugal night with his wife at his manor house at Bampton and,

after lodging his prisoner at the rectory in Deddington, he had gone home.

In his absence the Earl of Warwick had taken Gaveston and marched him barefoot

to Warwick Castle where he had imprisoned him. Lancaster and his men had

followed.

William recalled the day they had approached Warwick.

It had looked magnificent in the evening twilight and, as they urged their

weary horses up towards the towering stone ramparts, William saw that torches

had been lit to welcome them in. He had been sweating and thirsty all

day. He had a sore on one leg where his lined hose had bunched up under

the top of his cuisses and he was looking forward to a long drink of ale, a hot

supper, perhaps the chance to wash his feet as well as his hands and a decent

night’s sleep ‒ even though it would be on a pallet in a tent rather than

the comfort of his own feather bed at home in Haigh.

The hot day was still sultry with the promise of thunder in

the air and, as William handed his horse to one of the boys who had come

forward to take charge of the animals, he saw his friend and neighbour Adam

Banastre coming towards him. Adam nodded his head towards the

tight-lipped Earl of Lancaster who was climbing the wooden steps to the great

hall with an expression of grim satisfaction.

“If ever a man was bent on revenge,” he remarked, “it

is our lord and master.” And as William watched the earl disappear

inside, he agreed that Lancaster would not be satisfied until he saw Gaveston

dead.

The next morning William was one of the men whom Lancaster

had called to attend him. Once the court was assembled in the great hall

the Earl of Warwick had ordered the prisoner to be brought up from the dungeon

below where he had been held overnight. William watched as the door was

flung open and Gaveston, in chains, was thrust forward and pushed to his knees

on the floor rushes. It was the first time William had actually seen Piers

Gaveston though he had heard plenty about him and as he studied the tall, well-muscled

man he had to admit that it was hardly surprising he fared so well in the

jousting tournaments. He had already beaten all the knights of the earls

of

Arundel, Hereford and

Warenne, and they all hated him with a vengeance for his disgracing of them and

their households.