An Old Heart Goes A-Journeying (18 page)

Read An Old Heart Goes A-Journeying Online

Authors: Hans Fallada

They had got at Rosemarie, indeed, they had probably put her up to the whole scheme. And now, believing Schlieker safe in jail, they had hoped to get hold of the girl’s belongings as well as the girl, and had sent their villainous offspring, Otsche, for that purpose.

All this was clear as daylight to the Schliekers—what a blessed chance that Schlieker had been let out of jail in time to catch the boy red-handed and clap him in the cellar, where he could shout himself hoarse!

There were two alternatives: he could go to the magistrate and have the matter out in public with all the ensuing scandal and inquiries by the police. And the Schliekers certainly liked the prospect of the archenemy’s public humiliation.

But the other alternative, being more lucrative, was perhaps to be preferred. Schlieker would treat with Gau direct, and not merely exchange the boy for the treacherous Marie (how she would be made to writhe!), but extract a nice little sum in compensation for overlooking the theft—something that would help to pay

for the deceased cow. Gau was at Schlieker’s mercy—that was clear.

The sole objection to the second alternative was that it involved a personal interview with Wilhelm Gau. Everyone knew what he was like—indeed, he was the subject of a popular proverb.

Paul Schlieker was not a man of many parts, but he was well supplied with impudence. When Mali wailed, “He’ll kill you, Paul!” he merely laughed, and said, “I’ll kill him back.”

“No, get that parcel ready, and I’ll take the bicycle. If he won’t come to terms, or if he tries to fool me, I’ll go straight to the police at Kriwitz. Then they’ll search his house this very evening, and we’ll be rid of this little ruffian, and with the law behind us.”

“Oh, Paul,” she wailed, “he’s a dreadful man!”

“Oh, Mali!” he jeered. “I can be dreadful if I like. Keep the house locked up, and don’t let anyone take the boy away—or you’ll see a very dreadful fellow, and that will be me!”

He soon departed, arrayed in his blue Sunday jacket, not for Gau’s benefit, but in case he had to go on to town. He wheeled his bicycle with one hand, and carried the parcel in the other.

Had anyone suggested that his heart was beating a little faster at the prospect of this encounter with his ancient hereditary enemy, the ogre of Unsadel, Schlieker would have laughed. But it

was

beating faster, not indeed from fear, but at the prospect of triumph.

Farmer Wilhelm Gau was sitting at the table in the parlor. In the yard the cattle were still being fed and

milked. He was never a man to stand and watch, but when the work was done, he would go out and inspect it and woe to any man who had skimped his work—for Gau missed nothing.

Woe, indeed, to everyone and everything, woman, child, man, maid, and beast that thwarted Farmer Gau. He was the largest farmer in the district—not merely large as a landowner, he was also very large in person. Over six feet tall and weighing over two hundred and twenty-five pounds, he sat at the table in the darkening parlor, motionless, and blinking darkly into space.

Two deep lines furrowed his forehead just above his nose, marking him as a man of moods and evil humor, a man who hated life and his fellow beings. The lines were deep as scars and seemed to have been with him since childhood. They had. This huge and formidable man had never had his way. He had had to marry—for the sake of the farm—a vapid little creature instead of the woman he loved. Again for the sake of the farm he had been balked of his heart’s desire, which was to be a sailor.

When he had to say no to a cattle dealer, his wife the innkeeper, or his children, he never merely said no; he said, “The whole lousy show isn’t worth the trouble. . . .” By which he really meant that to him the whole lousy show had never been worth the trouble all his life. He never forgot that, not for a single minute. He worked, and he worked well, but when his work was done, he sat as he was sitting then, staring darkly into space.

This was the man upon whom the door opened, and a foxy little rascal called Paul Schlieker appeared with a parcel under his arm.

Schlieker peered into the twilit room, not quite sure whether the farmer was there or not, but the latter growled: “Not at home, get out.”

“I’ve brought along the washing,” grinned Paul Schlieker, and put the parcel on the farmer’s table.

The other listened; without lifting his head he recognized the visitor by his voice. “Right,” he said indifferently. “You can go.” Paul and Mali had imagined a pleasant scene when Gau was presented with the underclothes he had sent his son to steal. But the joke seemed to have failed, and Paul said in a more menacing tone: “You’re not going to get away with it, Wilhelm. Theft is theft.”

“Sure,” growled the looming shadow from the darkless. “You can bet on that, Paul.”

And Schlieker went on, as though he had heard nothing. “Folks will begin to talk a bit, Wilhelm, when they know that Gau steals children, and his son steals their underclothes. . . .”

“You’ve come to the wrong shop,” said Gau, motioness in the darkness. “You’d better go to Tamm’s.”

“And if we can’t come to some friendly agreement, Wilhelm, I shall go to the police and get a search warrant. . . .”

“Then go,” said the vast shadow.

Paul felt rather baffled, but he persevered. “Perhaps you haven’t heard, Wilhelm, that I caught your Otsche stealing on my farm, and I’ve got him under lock and key.”

“Good for you,” said the farmer, still immovable.

“But if you’ll hand over Marie Thürke, and—say—

three hundred marks for that cow, I’ll give up Otsche and I and Mali won’t say a word.”

“Liar!” said the farmer.

“Oh, no, we won’t, Wilhelm,” protested Schlieker. “We’ll hold our tongues; besides, it would be against our interest to talk.”

“Hey!” roared Gau; Schlieker recoiled, and swallowed his remaining comments. “Hey! Wife!”

The door opened.

“Yes, Father?” said the farmer’s wife.

“Send the boy in—at once!”

The door closed.

“We’ll have to wait quite a while,” jeered Schlieker. “I’ve got him locked up at home.”

“Take that rubbish off my table,” said the farmer. “You’ll soon find yourself and your rubbish, too, in the street! Take it away!” he roared, as the other hesitated.

Schlieker picked up the parcel. “There’s no reason to talk like that, Wilhelm,” he muttered. Then the door opened.

“Yes, Father?” said Otsche, struggling with his gasps.

“Blast that woman. . . .” began Paul Schlieker; but he got no further. . . .

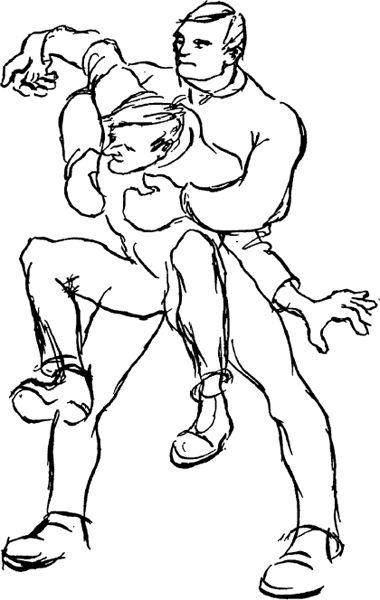

The table tipped over with a crash as the gigantic farmer leapt at his enemy. Schlieker, too, was handy with his fists, but he was helpless against such an onslaught. He staggered under a tornado of blows, he was kicked in the shins, jabbed in the stomach, buffeted in the face. He swayed, he choked, the blood gushed from his nose. Gau gripped him and Schlieker tried to speak, protest, explain. But he was dragged like a sawdust doll from

the parlor to the kitchen, and with a last terrific heave, hurled into the road, where he lay half stunned.

Farmer Gau shows Paul Schlieker the door

.

The farmer returned to the parlor.

“Pick up the table, Otsche,” he said. “And light a lamp.”

Otsche obeyed in silence, and his father sat down again on his wooden bench. He drew his son toward him until he held him between his knees, and eyed him darkly. The boy looked unblinking into his father’s face.

For a while they said nothing. Not a sound could be heard but the agitated whispers of the women in the kitchen. After a while Gau sighed, laid his large hands on his son’s shoulders and said: “You weren’t in the woodshed just now?”

“No, Father.”

“Who let you out?”

The son looked at his father.

“Well?—How about it?—Who let you out?—Be careful!”

The boy’s look was his only answer.

The farmer’s eyes darkened, he gripped the boy’s arm until the lad cried out.

“Well, who let you out?—” asked his father inexorably.

Otsche paled, but did not utter a sound.

“I’ll break your arm,” said his father.

The boy dropped his eyelids, his pale lips quivered, but he said no word.

The farmer pondered, then he slackened his grip on the boy’s arm and said: “You were in Schlieker’s house?”

“Yes,” whispered the son.

“Had you gone there to steal?”

Otsche reflected. The great inexorable hands tightened their grip, and the son said hastily: “Do Rosemarie’s things belong to her or to the Schliekers?”

“What sort of things?”

“Clothes, underclothes, shoes. . . .”

“To Marie.”

“Then I wasn’t stealing.”

“Did Marie ask you to get them?” asked the farmer slowly.

Otsche reflected for a moment, and then said, “Yes.”

Wilhelm Gau pondered once more. “Where is Marie?” he asked.

The son reflected. “Now?”

“Yes, now.”

“I don’t know, Father,” he said hurriedly.

“That’s a lie!” And the hands tightened.

“It’s not a lie, Father!” cried Otsche. “Let go my arm, Father, it’s not a lie.”

The hands did not release him but their grip slackened. “Is Marie in this house?”

“No, Father,” exclaimed Otsche. “What an idea!”

“Have you had her in this house?”

“No, Father.”

“Did you mean to bring her to this house?”

“No, Father.”

“How did you come to be doing what Marie tells you?”

“I’ve made up with her again.”

“So,” said the farmer ominously. “Made up, have you—with the little brat who left us for the Schliekers? And now you want to rescue her from them.”

“She’s got away from them already.”

“Where is she?”

“I won’t tell.”

The hands now gripped so savagely that the boy quivered and vomited. With a last effort he blurted out: “I’ll drown myself, Father, if you force me to tell you. I’ve given my word. . . .”

Farmer Wilhelm Gau laughed, he was really amused to see himself defied by this little urchin. “Where is Marie?” he asked and the hands gripped harder and yet harder.

The son looked desperately at the father with half-closed eyes. He knew he could not bear this agony a moment longer and would betray his trust. Suddenly he bent down and bit one of those torturing hands so hard that the farmer bellowed with pain and let him go.

Otsche staggered back to the farther end of the room, and would have fled, but his father was between him and the door.

Gau looked incredulously at his bleeding hand, and muttered: “He bit me . . . bit his own father?”

The farmer looked up, and stared quizzically at his small son, who, still pale and trembling but undaunted, defied him still.

“Come here, Otsche,” he said.

Otsche eyed his father doubtfully. But something reassured him—the ring of his father’s voice, or the look in his father’s eyes, and he came.

“You bit your father. . . .” said Wilhelm Gau.

The boy looked at him.

“And what’s to be done now?” said his father, raising his undamaged fist.

The boy did not blink, something in his father’s voice had changed.

“What would your master say if he knew one of his pupils had bitten his father?” asked the farmer mockingly, and lowered his fist.

“He’d thrash me,” said the boy, but there was a faint glitter in his eye.

“And what would the boy’s father do?”

“Thrash me too.”

“And you bit me all the same?”

The farmer stared at the hand, from which blood was dripping on to the table.

“Get a handkerchief out of the chest of drawers,” said he, “and bind my hand up—What do you want to be, by the way?”

“A farmer,” said Otsche, rummaging in the drawer.

“Why? Because you like farming? Or because you’re the only boy on the farm?”

“Because I like farming,” said the son, twisting the handkerchief round his father’s hand.