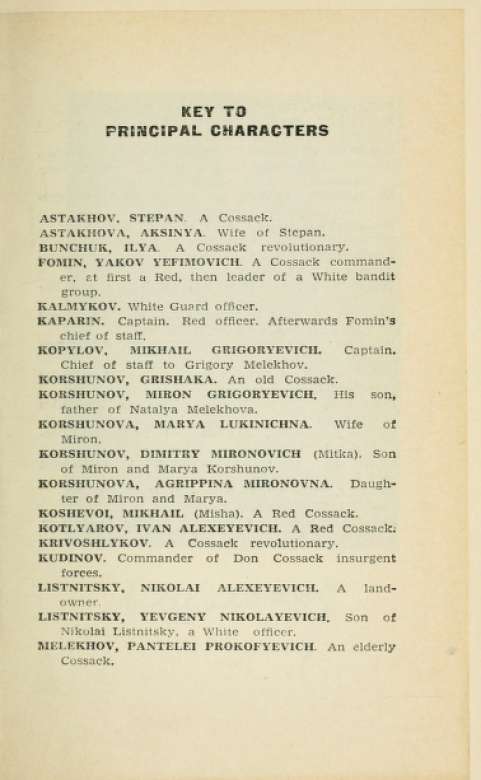

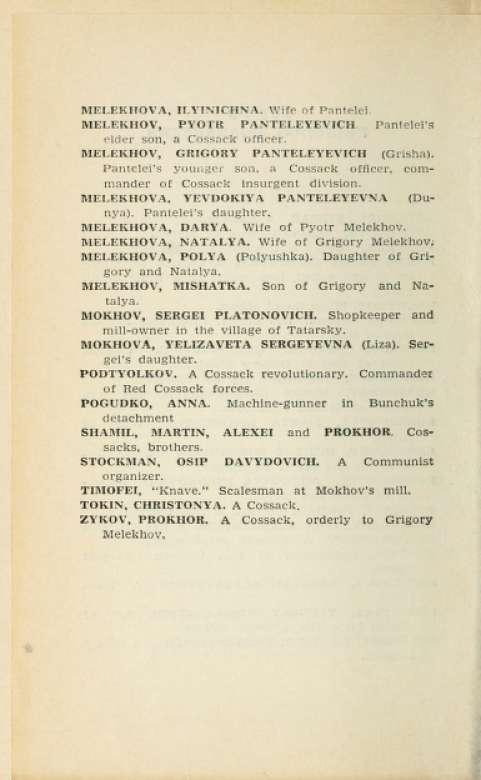

And quiet flows the Don; a novel

Read And quiet flows the Don; a novel Online

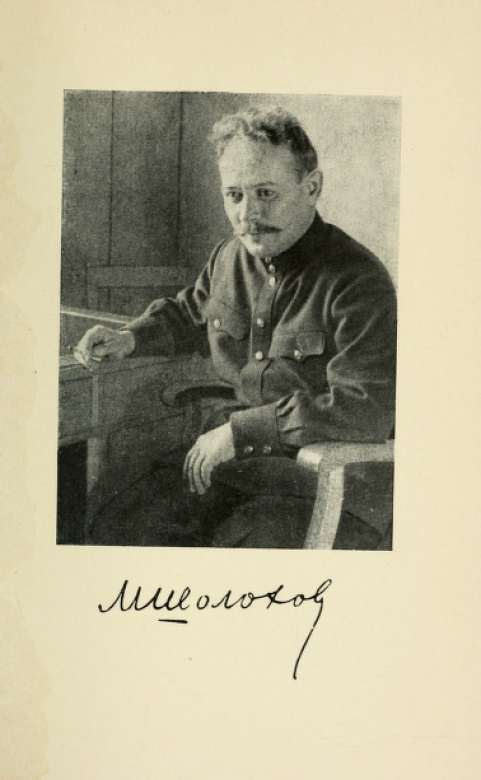

Authors: 1905- Mikhail Aleksandrovich Sholokhov

Tags: #World War, 1914-1918, #Soviet Union -- History Revolution, 1917-1921 Fiction

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

v.l

BOOK ONE

Not by the plough is our glorious earth furrowed..,.

Our earth is turrowed by horses' hoots.

And sown is our earth with the heads of Cossacks.

Fair is our quiet Don with young widows.

Our father, the quiet Don, blossoms with orphans.

And the waves of the quiet Don are filled

with fathers' and mothers' tears.

Oh thou, our father, the quiet Don!

Oh why dost thou, our quiet Don, so sludgy flow?

How should I, the quiet Don, but sludgy Row!

From my depths the cold springs beat.

Amid me, the quiet Don, the lohite fish leap.

Old Cossack Songs.

PART ONE

T

he Melekhov farm was at the very end of the village. The gate of the cattle-yard opened northward towards the Don, A steep, fifty-foot slope between chalky, moss-grown banks, and there was the shore. A pearly drift of mussel-shells, a grey, broken edging of wave-kissed shingle, and then-the steel-blue, rippling surface of the Don, seething in the wind. To the east, beyond the willow-wattle fences of threshing-floors-the Hetman's highway, grizzled wormwood scrub, the hardy greyish-brown, hoof-trodden plantain, a cross standing at the fork of the road, and then the steppe, enveloped in a shifting haze. To the south, a chalky ridge of hills. To the west, the street, crossing the square and nmning towards the leas.

The Cossack Prokofy Melekhov returned to the village during the last war but one with

//

Turkey, He brought back a wife-a little woman wrapped from head to foot in a shawl. She kept her face covered, and rarely revealed her wild, yearning eyes. The silken shawl bore the scent of strange, aromatic perfumes; its rainbow-hued patterns aroused the envy of the Cossack women. The captive Turkish woman kept aloof from Prokofy's relations, and before long old Melekhov gave his son his portion. All his life the old man refused to set foot inside his son's house; he never got over the disgrace.

Prokofy speedily made shift for himself; carpenters built him a house, he himself fenced in the cattle-yard, and in the early autumn he took his bowed foreign wife to her new home. He walked with her through the village, behind the cart laden with their worldly goods. Everybody, from the oldest to the youngest, rushed into the street. The men laughed discreetly into their beards, the women passed vociferous remarks to one another, a swarm of unwashed Cossack children shouted catcalls after Prokofy. But, with overcoat unbuttoned, he walked slowly along, as though following a freshly-ploughed furrow, squeezing his wife's fragile wrist in his own enormous, black palm, and holding his head with its straw-white mat of curls high in defiance. Only the wens below his cheek-bones

swelled and quivered, and the sweat stood out between his stony brows.

Thenceforth he was rarely seen in the village, and never even attended the Cossack gatherings. He lived a secluded life in his solitary house by the Don. Strange stories were told of him in the village. The boys who pastured the calves beyond the meadow-road declared that of an evening, as the light was dying, they had seen Prokofy carrying his wife in his arms right as far as the Tatar burial mound. He would set her down, with her back to an ancient, weather-beaten, porous rock, on the crest of the mound, sit down at her side, and they would gaze fixedly across the steppe. They would gaze until the sunset had faded, and then Prokofy would wrap his wife in his sheepskin and carry her back home. The village was lost in conjecture, seeking an explanation for such astonishing behaviour. The women gossiped so much that they had not even time to search each other's heads for lice. Rumour was rife about Prokofy's wife also; some declared that she was of entrancing beauty; others maintained the contrary. The matter was settled when one of the most ^venturesome of the women, the soldier's wife Mavra, ran along to Prokofy's house on the pretext of getting some leaven; Prokofy went down into the cellar for the

leaven, and Mavra had time to discover thai Prokofy's Turkish conquest was a perfect fright.

A few minutes later Mavra, her face flushed and her kerchief awry, was entertaining a crowd of women in a by-lane:

"And what could he have seen in her, my dears? If she'd only been a woman now, but a creature like her! Our girls are far better covered! Why, you could pull her apart like a wasp. And those great big black eyes, she flashes them like Satan, God forgive me. She must be near her time, God's truth."

"Near her time?" the women marvelled.

"I wasn't bom yesterday! I've reared three myself."

"But what's her face like?"

"Her face? Yellow. No light in her eyes-doesn't find life in a strange land to her fancy, I should say. And what's more, girls, she wears . , . Prokofy's trousers!"

"No!" the women drew in their breath together.

"I saw them myself; she wears trousers, only without stripes. It must be his everyday trousers she has. She wears a long shift, and underneath you can see the trousers stuffed into socks. When I saw them my blood ran cold."

The whisper went round the village that Prokofy's wife was a witch. Astakhov's daughter-

in^aw (the Astakhovs were Prokofy's nearest neighbours) swore that on the second day of Trinity, before dawn, she had seen Prokofy's wife, barefoot, her hair uncovered, milking the Astakhovs' cow. Since then its udder had withered to the size of a child's fist, the cow had lost its milk and died soon after.

That year there was an unusual dying-off of cattle. By the shallows of the Don fresh carcasses of cows and young bulls appeared on the sandy shore every day. Then the horses v/ere affected. The droves grazing on the village pasture-lands melted away. And through the lanes and streets of the village crept an evil rumour.

The Cossacks held a meeting and went to Pro-kofy. He came out on tlie steps of his house and bowed.

"What can I do for you, worthy elders?"

Dumbly silent, the crowd drew nearer to the steps. One drunken old man was the first to cry:

"Drag your witch out here! We're going to try her. . . ."

Prokofy flung himself back into the house, but they caught him in the passage. A burly Cossack, nicknamed Lushnya, knocked his head against the wall and told him:

"Don't make a row, there's no need for you to shout. We shan't touch you, but we're going to trample your wife into the ground. Better to de-

stroy her than have all the village die for want of cattle. But don't you make a row, or I'll smash the wall in with your head!"

"Drag the bitch out into the yard!" came a roar from the steps. A regimental comrade of Prokofy's wound the Turkish woman's hair around one hand, clamped his other hand over her screaming mouth, dragged her at a run across the porch and flung her under the feet of the crowd. A thin shriek rose above the howl of voices. Prokofy flung off half a dozen Cossacks, burst into the house, and snatched a sabre from the wall. Jostling against one another, the Cossacks rushed out of the house. Swinging the gleaming, whistling sabre around his head, Prokofy ran down the steps. The crowd drew back and scattered over the yard.

Lushnya was heavy on his feet, and by the threshing-floor Prokofy caught up with hiin; with a diagonal sweep down across the left shoulder from behind, he clave the Cossack's body to the belt. The crowd, who had been tearing stakes out of the fence, fell back, across the threshing-floor into the steppe.

Half an hour later the Cossacks ventured to approach Prokofy's farm again. Two of them stepped cautiously into the passaae, O'l the kitchen threshold, in a pool of bloci, her head flung back awkwardly, lay Prokofy . wif^; her

lips were writhing tormentedly, her gnawed tongue protruded. Prokofy, with shaking head and glassy stare, was wrapping a squealing little ball-the prematurely-born infant-in a sheepskin.

Prokofy's wife died the same evening. His old mother had compassion on the child and took charge of it. They plastered it with bran-mash, fed it with mare's milk, and, after a month, assured that the swarthy, Turkish-looking boy would survive, they carried him to church and christened him. They named him Pantelei after his grandfather. Prokofy came back from penal servitude twelve years later. With his clipped, ruddy beard streaked with grey and his Russian clothing, he did not look like a Cossack. He took his son and returned to his farm.

Pantelei grew up swarthy, and ungovernable. In face and figure he was like his mother. Prokofy married him to the daughter of a Cossack neighbour.

From then on Turkish blood began to mingle with that of the Cossack, And that was how the hook-nosed, savagely handsome Cossack family of Melekhovs, nicknamed "Turks," came into the village.

When his father died Pantelei took over the farm; he had the house rethatched, added an acre of common land to the farmyard, built new

sheds, and a barn with a sheet-iron roof. He ordered the tinsmith to cut a couple of weathercocks out of the scrap iron, and when these were set up on the roof of the barn they brightened the Melekhov farmyard with their carefree air, giving it a self-satisfied and prosperous appearance.

Under the weight of the passing years Pante-lei Prokofyevich grew gnarled and craggy; he broadened and acquired a stoop, but still looked a well-built old man. He was dry of bone, and lame (in his youth he had broken his leg while hurdling at an Imperial Review of troops), he wore a silver half-moon ear-ring in his left ear, and his beard and hair retained their vivid raven hue until old age. When angry, he completely lost control of himself and undoubtedly this had prematurely aged his buxom wife, whose face, once beautiful, was now a perfect spider-web of furrows.

Pyotr, his elder, married son, took after his mother: stocky and snub-nosed, a luxuriant shock of corn-coloured hair, hazel eyes. But the younger, Grigory, was like his father: half a head taller than Pyotr, some six years younger, the same pendulous hawk nose as his father's, the whites of his burning eyes bluish in their slightly oblique slits; brown, ruddy skin drawn tight over angular cheek-bones. Grigory stooped

slightly, just like his father; even in his smile there was a similar, rather savage quality.

Dunya-her father's favourite-a lanky large-eyed lass, and Pyotr's wife, Darya, with her small child, completed the Melekhov household.

II

Here and there stars still hovered in the ashen, early morning sky. The wind blew from under a bank of cloud. A mist rolled high over the Don, piling against the slope of a chalky hill, and creeping into the gullies like a grey, headless serpent. The left bank of the river, the sands, the wooded backwaters, the reedy marshes, the dewy trees, flamed in the cold, ecstatic light of dawn. Below the horizon the sun smouldered, and rose not.

In the Melekhov house Pantelei Prokofyevich was the first to awake. Buttoning the collar of his embroidered shirt, he walked out on to the steps. The grassy yaid was spread with a dewy silver. He let the cattle out into the street. Darya ran past in her shift to milk the cows. The dew sprinkled over the calves of her bare white legs, and she left a smoking, flattened trail behind her over the grass of the yard. Pantelei Prokofyevich stood for a moment watching the grass

rise from the pressure of Darya's feet then lurned back into the best room.

On the sill of the wide-open window lay the dead rose petals of the cherry-trees blossoming in the front garden. Grigory lay asleep face downward, one arm flung out sideways.

"Grigory, coming fishing?"

"What?" Grigory asked in a whisper, dropping his legs off the bed.

"Come out and fish till sunrise."

Breathing heavily through his nose, Grigory pulled his everyday trousers down from a peg, drew them on, tucked the legs into his white woollen socks, and slowly put on his sandals, straightening out the trodden-down heel.

"But has Mother boiled the bait?" he asked hoarsely, as he followed his father into the porch.

"Yes. Go to the boat. I'll come in a minute."

The old man poured the strong-smelling, boiled rye into a jug, carefully swept up the fallen grains into his palm, and limped down to the beach. He found his son sitting hunched in the boat.

"Where shall we go?"

"To the Black Bank. We'll try around the log where we were sitting the other day."

Its stern scraping the ground, the boat broke away from the shore and settled into the water.

The current carried it off, rocking it and trying to turn it broadside on. Grigory steered with the oar, but did not row.

"Why aren't you rowing?"

"Let's get out into midstream first."

Cutting across the swift mainstream current, the boat moved towards the left bank. The crowing of the village cocks rang out after them across the water. Its side scraping the black, craggy bank rising high above the river, the boat slid into the pool below. Some forty feet from the bank the twisted branches of a sunken elm emerged from the water. Around it turbulent flecks of foam eddied and swirled.

"Get the line ready while I scatter the bait," Pantelei whispered. He thrust his hand into the steaming mouth of the jug. The rye scattered audibly over the water, like a whispered "Sh-sh." Grigory threaded swollen grains on a hook, and smiled.

"Come on, you fish! Little ones and big ones too."

The line fell in spirals into the water and tautened, then slackened again. Grigory set his foot on the end of the rod and fumbled cautiously for his pouch.

"We'll have no luck today. Father. The moon is on the wane."

"Bring any matches?"

"Uh-huh."

"Give me a light."

The old man began to smoke, and glanced at the sun, stranded beyond the elm.

"You can't tell when a carp will bite/' he replied. "Sometimes he will when the moon is waning."

"Looks as if the small fish are nipping the bait," Grigory sighed.

The water slapped noisily against the sides of the boat, and a four-foot carp, gleaming as though cast from ruddy copper, leaped upward with a groan, threshing the water with its broad, curving tail. Big drops of spray scattered over the boat.