And the Sea Will Tell (9 page)

Read And the Sea Will Tell Online

Authors: Vincent Bugliosi,Bruce Henderson

As the air cooled, then became chill, a powerful northeasterly began to blow, urging them strongly and precisely in the direction of Palmyra Island.

Mac, at last, had what he wanted. They were heading into the unknown, and he was exuberant.

CHAPTER 7

T

HOUGH DESIGNATED AN ISLAND

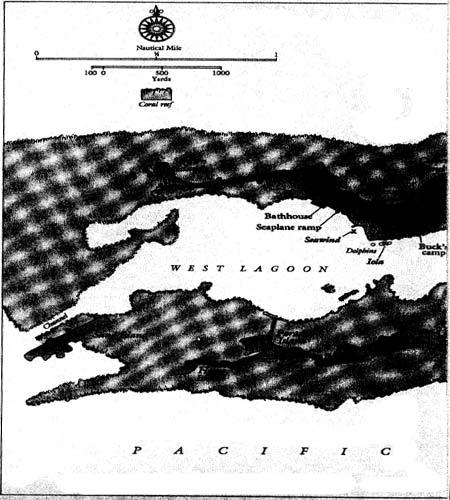

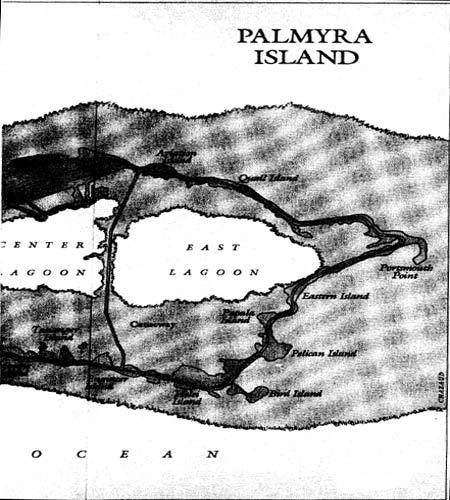

on some charts of the Pacific, Palmyra is in fact an atoll, the very rim of a steep-faced volcanic peak in a gigantic underwater range whose mountains, hidden deep within the ocean, are among the world’s highest. Unlike actual islands, atolls are virtually flat, with no hills or mountains. Palmyra’s highest elevation is only six feet above sea level.

A horseshoe curve of more than a dozen islets are spaced like jewels on a long necklace surrounding a protected lagoon—the old volcano crater—a configuration common to atolls. Each islet is composed of hard sand and constantly growing coral, carpeted with a dense growth of shrubs and coconut palms.

For centuries this ancient atoll lay undiscovered, six degrees north of the equator, near the zone where the northeast and southeast trade winds meet and tussle.

On the night of June 13, 1798, Edmond Fanning, an intrepid American sea captain, was sailing his ship, the

Betsey

, northwestward toward home from a trading trip to the Orient. Fanning, a well-known sailor of fortune, had already discovered a Pacific island that now bore his name. Suddenly, struck in his cabin by a compelling premonition of danger, Fanning hurried on deck and briskly ordered the helmsman to heave to in the darkness. Astonishingly, the first dim light of early dawn disclosed a low reef, dead ahead. Fanning’s ship would surely have foundered there had he not trusted his mariner’s sixth sense. With heady relief, the

Betsey

’s crew upped sail and carefully rounded the reef on its northern flank. Fanning climbed aloft to the crow’s nest high atop the mainmast. Through his spyglass, he saw a small, unprepossessing island on the opposite side of the reef. This is the first recorded view of Palmyra, and the

Betsey

’s brush with destruction became the first omen of danger to be associated with the island.

The island was officially christened when a second ship chanced by and gained credit for the actual discovery, Fanning having failed to make a timely report of his finding. On November 6, 1802, a Manila-bound American ship, the

Palmyra

, was thrown off course in heavy seas and pushed near the island by the elements. When the weather cleared, the crew went exploring ashore, and occupied themselves on the atoll for about a week. It took nearly four years for a dispatch from the

Palmyra

’s skipper, Captain Sawle, to be relayed from one vessel to another and finally reach home with the news:

New island, 05° 52' North, 162° 06' West, with two lagoons, the westmost of which is 20 fathoms deep, lies out of the track of most navigators passing from America to Asia or Asia to America.

Fourteen years later, a Spanish pirate ship, the

Esperanza

, kept a grim appointment with destiny in the waters off Palmyra. Sailing with a rich cargo of gold and silver artifacts stolen from Inca temples in northern Peru, the vessel was attacked by another ship, and a bloody battle ensued. Surviving

Esperanza

crew members managed to sail her off with the treasure intact, but soon wrecked on submerged coral reef. As the ship sank, the pirates successfully transferred their treasure and provisions to the nearby deserted atoll: Palmyra. The following year the stranded men built rafts, split into two groups and, after hiding their treasure, sailed off in opposite directions for help. It is known that one raft sank. An American whaler found and rescued its only survivor, seaman James Hines, who soon died of pneumonia. None of the crew members on the other raft was ever heard from; it is assumed all died at sea. And since no one has ever reported finding the Inca cache on Palmyra, it might still rest there, a collection of Mesoamerican objects several times more valuable in today’s art market than the gold and silver would be as precious metals.

The litany of disasters had scarcely begun. In late 1855, word reached Tahiti that another ship, a whaler, had wrecked on Palmyra’s treacherous reefs, but an attempt to find the missing ship and her crew was unsuccessful.

In 1862, Hawaii’s King Kamehameha IV granted a petition from two subjects of his, Zenas Bent and J. B. Wilkinson, for authorization to take possession of Palmyra under the Hawaiian flag. Bent and Wilkinson treated the island as virtually their own, building a rudimentary house, planting a vegetable garden, and leaving “a white man and four Hawaiians” there to “gather and cure

biche de mer

,” an edible sea slug prized in the Orient. Later that year, Bent sold his interest in Palmyra to Wilkinson, who in turn willed his proprietary interest in the property to his Hawaiian wife. Palmyra was included among the other Hawaiian Islands when they were annexed to the United States by act of Congress in 1898.

In 1911, Judge Henry E. Cooper of Honolulu purchased Palmyra for $750 from the heirs of Wilkinson’s widow. He kept Palmyra and adjacent properties until 1922, when he sold off all but one islet for $15,000. The old judge apparently believed a rumor that the treasure of the

Esperanza

was buried under a banyan tree on that islet—called Home Island. The new owner of the remainder of Palmyra, Leslie Fullard-Leo, a South African diamond miner turned building contractor, had heard about Palmyra shortly after moving to Honolulu and thought it likely to be a peaceful refuge far removed from the rigors of civilization. But Fullard-Leo visited his uninhabited island only twice in seventeen years. When he died, Palmyra was inherited by his three sons, who also rarely visit it. Home Island has passed on to Judge Cooper’s descendants.

The Fullard-Leo family was forced into a legal skirmish with the U.S. government to keep Palmyra. In anticipation of the expected Pacific war, Palmyra was declared a “prohibited defense area” by an Executive Order dated December 19, 1940, and assigned to the jurisdiction of the Navy Department, which constructed a naval base there for five thousand servicemen. The Fullard-Leos resisted in four federal court battles. The clincher came in 1946, when the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals declared the brothers’ title to Palmyra Island valid. The court held that since both occupancy and claim of title to Palmyra by Bent, Wilkinson, and their heirs (buttressed by regular payment of property taxes) existed long prior to U.S. annexation of Hawaii, and were honored by the Hawaiian government, Palmyra was in fact privately owned, even though it is a “possession” of the United States. Soon after the circuit court’s decision, the Navy swiftly pulled out, abandoning buildings, gun emplacements, and empty ammunition dumps.

Since Palmyra’s status as private property had been affirmed, visitors like Mac, Muff, Buck, and Jennifer needed permission from the owners to spend any time there, but the Fullard-Leos, who live in Honolulu, had learned long ago that it was impossible to keep uninvited guests off their island. Sensitive to what South Sea sailors had long called the Palmyra Curse, her owners took out substantial liability insurance to protect them from a host of calamities that might occur to visitors on their island, and hoped for the best.

J

UNE

27, 1974

A

S THE

Iola

was towed into the lagoon, Jennifer was struck with the feeling that time had come to a halt on Palmyra. The lagoon, smooth as a mirror and so clear one could make out the coral configurations on its bottom, was flanked on three sides by miniature islands, each overgrown with tall coconut trees marching down to the waterline. The island was as pristine as she had hoped.

But Palmyra, though uninhabited, was not, as she and Buck had hoped, a deserted island.

On the north side of the lagoon they moored the

Iola

between two other boats at a line of steel-reinforced wooden pilings (four, in all) that boaters call “dolphins.” Scarcely fifteen yards of water separated the

Iola

from shore, and the boats on each side of it were around twenty yards distant. Jennifer and Buck, with a cargo of excited dogs, rowed their dinghy the short distance to the beach, where the pent-up animals went crazy and gamboled madly, barking and yapping and running around in circles.

As Jennifer planted her feet on solid ground for the first time in twenty-eight days, the earth seemed to be shifting under her. She was ecstatic to be off the boat and safe after an ocean voyage of a thousand miles. From where she stood, she could smell the earthiness, the fertile greenery of the jungle. It pulsed with hidden life.

Jennifer, her eyes moist with happiness, hugged Buck tightly. The warm, bright sun enhanced the specialness of the moment.

They were soon introducing themselves to the other people on the island. One of the neighboring boats was the

Poseidon

, a forty-eight-foot ketch owned by Jack Wheeler. He and his lively teenage son, Steve, had manned one of the dinghies that towed the

Iola

. Also aboard Wheeler’s boat were his wife, Lee, and their attractive daughter, Sharon. The other boat was the

Caroline

, a forty-four-foot motor-sailer with twin diesel engines that was on a charter out of Honolulu and skippered by Larry Briggs, who had been in the other dinghy.

“How was your trip?” someone asked.

“

Long

,” Jennifer said, smiling. “Took us nineteen days from Port Allen. And we sat outside the channel here for over a week, waiting for the wind to shift so we could sail in.”

“Sorry to hear that,” Jack Wheeler said. “Welcome to Palmyra anyhow.”

Wheeler, fiftyish, was a wiry man with long sideburns and horn-rimmed glasses that rested near the end of his nose. He volunteered to take Jennifer and Buck on a tour of the island, “seeing as how I’m kinda the unofficial mayor of this place.” There was the hint of unspoken challenge in his tone.

As they began walking, Wheeler explained that they were on the biggest islet—Cooper Island.

“Named for an old judge, I’m told. All these islets were connected together by the Seabees during the war. The road that hooked them up is now gone in lots of places. The causeway through the lagoon is pretty broken down, too. Best thing to do if you want to get around to the other side of the lagoon is to take a dinghy right across.”

Just before they entered the jungle, Wheeler pointed out a clearing adjacent to his boat. “We have a nice fireplace there for outdoor cooking. You’ll have to try some of the wife’s smoked fish.”

Wheeler smiled knowingly. “Now, you know about the poisonous fish?”

“Poisonous?” Jennifer said, her expression tightening. She looked at Buck for his reaction, but he disguised his surprise. They had both been counting on a diet rich in fish.

“Yeah. Ciguatera is what I’m talking about. The fish carry a toxin produced by a certain kind of algae here. You also see it in Hawaii and the Caribbean. Even Florida. But there are a few varieties of fish that are edible, and tasty, too. Papio are excellent eating, and they’re all over the place. Mullet are good, too, but leave the red snapper alone. They’re good eating back home, but you’ll get mighty sick if you eat them here. We had a cat with us on a trip here some years back. We’d feed her a piece of fish and then watch to see if she threw up. If she kept it down, we figured it was all right.”

Jennifer was appalled by this apparent insensitivity. “Weren’t you worried about killing the cat?”

“Naw. Cats are different. If people and dogs eat something that’s poisonous, they can get real sick, even die. A cat will just puke.”

As far as sea life was concerned, Jennifer told Wheeler what was uppermost in her mind: Buck’s scary run-in with the shark.

Wheeler nodded sagely. “They’re as thick as fleas on a hound. The lagoon’s a breeding ground for blacktip sharks. They’re one of the most aggressive sharks in the Pacific. Get up to six feet long. Be careful about taking a dip.”

“Don’t worry,” Jennifer said with a shudder. She had no intention of even wading in the picturesque lagoon. Its peaceful aspect was all illusion, she thought. Part of the dream had soured.