Andromeda Klein (12 page)

Authors: Frank Portman

vii.

No single magical text, perhaps, has had more impact on modern magic than

The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage

. A corrupt late French manuscript version of this mid-fifteenth-century grimoire was translated into English by Golden Dawn founder Samuel Liddle MacGregor Mathers. Then, the most influential magician of the twentieth century, Aleister Crowley, interpreted its ideas for use in modern times and used the Abramelin Operation as the basis of his own system, changing the face of practical occultism from that point forward. The text describes a lengthy magical operation intended to allow the practitioner to achieve “knowledge and conversation of” his Holy Guardian Angel. Once summoned, the Holy Guardian Angel, or HGA, as the entity is often known, instructs the practitioner and guides his further magical development.

Daisy had, from time to time, announced her intention to perform the Abramelin Operation. That was an absurdity. The Operation requires a strenuous period of magical retirement, of isolation from society, for a period of at least six, and possibly even as long as eighteen, months. Andromeda couldn’t see how anyone could manage it. You’d have to be rich, and have tons of time on your hands; and most of all, it would be best if the practitioner happened not to have a mother who was liable to burst into the temple at any moment to accuse the magician of putting her iPod in the refrigerator. In any case, it was not something to be taken lightly: Mathers, by the mere act of translating the text and transcribing the magic squares, so it was said, inadvertently conjured a horde of demons, who then pursued and hounded him to his doom.

Still, it was an important text. The International House of Bookcakes’s copy of

The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage

had been on the Sylvester Mouse list but had been missing for some time. That is, Andromeda had staff-checked it long ago and somehow managed to lose track of it. It was still, technically, checked out to her. The sinister nature of the Sylvester Mouse Project was such a shock that she hadn’t stopped to consider till much later that night what might happen to her if she couldn’t replace it. She’d be charged for the book, perhaps. But worse, Darren Hedge would certainly suspect her of stealing it, given her well-known interests and her outburst that day.

She needed a Sylvester Mouse strategy. She simply couldn’t function without the library’s collection, especially the 133s and 296s. She needed it for her work, not to mention to help her get to the bottom of the Daisy and King of Sacramento problems, and she had been counting on its continued existence and availability to any future self of hers that might have need of it. This was why she had donated

True and Faithful

and

Nightside of Eden

, thinking there was nowhere as safe as a public, little-used facility. Surely she should at least be able to get those back?

Many of the most important 133s were already gone, packed up and sent to the “Friends.” Unless she could acquire a great deal of cash to buy them back herself when they came up for auction, they would soon be gone forever. So it was Andromeda Klein against the world, or more accurately, Andromeda Klein against the “Friends” of the Library.

She hadn’t been able to bring herself to put

S.S.O.T.B.M.E

. and

Shadows of Life and Thought

back on the cart in the end, and she had returned them to her bag once Gordon had left. She wasn’t sure what she was going to do with them, or regarding anything. And there was the Lacey problem. The Daisy problem. The St. Steve problem. The Language Arts journal problem. No wonder she had trouble sleeping. Action-population late at night always caused insomnia, so the King of Sacramento was unable to make an appearance, despite the sigil.

And yet, the

Abramelin

problem, at least, had managed to resolve itself by the time of Rosalie van Genuchten’s “small and sensual get-together” the following afternoon. That is, when Andromeda Klein finally found herself standing at Rosalie van Genuchten’s door, she would be wearing a blond wig, a vinyl coat, and a studded belt with a skull buckle, and she would have

The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage

in her bag.

The dad was in the living room quietly playing his guitar with his eyes closed when she got home from work. He was at a low ebb, having recently switched to new meds, because the clinic had run out of free samples of what he had been on previously. The transitions were always difficult. Family and friends were supposed to watch carefully and note behavior changes when medication was initiated or changed, because the person taking it couldn’t always see themselves clearly. Andromeda had had lots of practice with the dad, and so had taken careful notes of Daisy’s behavior when Daisy had gone on Paxil. There had been no change, however; Daisy’s behavior had remained just as inconsistent and erratic, and had defied understanding right up to the end, though she had said she had much, much more vivid dreams after the Paxil kicked in.

“Cupcake,” the dad said mournfully. He tried to smile at her, and it didn’t work out too well. She knew where he was coming from with that. She Dave-claw-saluted him, and unlike the basketball boys, he returned the salute.

“Bad night?” she said.

“The baddest,” he replied.

“Me too,” she said, and she told him, a bit, about the “Friends” of the Library and

Babylonian Liver Omens

. She didn’t mention Lacey and “constantration camp.” It would have been too much for him in his current state.

The dad made a sympathetic face.

“The first step to controlling the people is preventing the free exchange of information,” he said, brightening slightly, warming to his favorite subject. “They burn the books, then they take the guns away. Soon everything is a crime, your neighbors turn you in, and the state confiscates your worldly goods. And the entire population is either in prison, on trial, or on parole or being investigated. Sound familiar? It’s an old, old story.” It was a good try, but his heart wasn’t really in it, she could tell.

They both winced as the mom suddenly slammed something in the kitchen, then winced again as she slammed the kitchen door and sat down at the computer. It was a wonder the door was still on its hinges and that the keyboard didn’t break under the violent assault of her fingers.

“Home sweet home,” said Andromeda cheerily.

“Rim shot,” the dad said in his Groucho Marx voice. He slapped the top of the guitar, which was lying faceup on his lap, with his two hands and then knocked it with his elbow, in a

bada smack

rhythm. He often did this rim-shot impression on tables, but on the guitar it made a hollow echo and sounded all the strings faintly. “It’s been a hard day’s night,” he sang under his breath, and let his voice trail off…. “You don’t know ‘Hard Day’s Night,’” he said. “People think the open strings sound like that first chord, so …” He sighed. “No wonder no one gets my jokes around here.”

Andromeda had no idea what he was talking about. Guillaume de Machaut was about as modern as her taste could handle, and he was mid-fourteenth century. She didn’t get it. The music her friends listened to, their boyfriends’ rock groups, and popular hits, it was all unnerving, chaotic, anxiety-inducing. She preferred her ancient and medieval music, the

ars nova

or

ars subtilior

, or, in a pinch, classical, orderly music, which made the world seem more sane while it was playing. The Goldberg Variations. That was what she needed at the moment. Something to organize her mind.

“I do sometimes,” she said, however. “Get your jokes. Go on, try me. Play something jokey.”

He picked up the guitar again and began to play and sing to a familiar tune:

“Joy to the world

The teacher’s dead

We cut off her head …”

The mom stomped up the hallway and glared at them before heading into the bedroom and slamming the door.

“Not a great review,” said Altiverse AK. The song was so ridiculous it was kind of funny, and Andromeda found herself kind of smiling.

“But wait,” said the dad. “There’s more.” He continued.

“What happened to the body?

We flushed it down the potty

.

And round and round she goes

,

And round and round she goes

,

And rou-ow-ow-ow-ow and round she goes …”

He looked at her seriously and raised his eyebrows. She returned the look. Then they raised and lowered their eyebrows together, hers going down as his went up, till they lost the rhythm.

“What the hell is that?” said Andromeda. “It’s so”—she paused with a mock-serious expression, as if searching for the right word, then continued—“stupid!” He was such a goofball.

“It is a well-known teacher song. Don’t you have any of those?”

She didn’t. Andromeda couldn’t imagine how it must have been, when teachers were important enough in kids’ lives that they took the trouble to make up songs to popular tunes to ridicule them. She could think of no teacher she had ever had who had ever been much more than a feebleminded irrelevancy. In her head she tried it out, but “Joy to the world, the ‘Friends’ of the Clearview Park Library are dead” wouldn’t fit into the song; she did better with Lacey.

“Hey, Dad,” said Andromeda, before she left him to his strumming. “How do you know Clearview is hell?”

He was blank for a bit, then he said: “I don’t know, Mrs. Teasdale, how

do

you know Clearview is hell?” Mrs. Teasdale was Margaret Dumont’s character in

Duck Soup

, and Andromeda was sure she was the only person in the whole town other than the dad who knew that.

She supplied her punchline about damned Christians, and was rewarded by a real smile and a genuine laugh.

“That’s a hot one!” he said. “A-plus. So there are still a lot of steak antlers down at your school?” He meant “snake handlers,” another of his terms for religious people, roughly equivalent to

godbotherers

.

“You know it,” she said, pleased with herself for managing to cheer at least one person up, and allowing herself to enjoy “steak antlers.”

Dave was scratching on the vacuum door when she walked past. He had probably been hiding—he hated noise, and the guitar most of all—and the mom had closed the door on him without realizing he was in there. He bounded out with a yowl.

Andromeda had a vague idea that if she was ever going to read

Shadows of Life and Thought

this might be her only chance, so she banished the room and lit her single candle and opened up the book. But she was too action-populated to concentrate on anything as difficult as A.E.’s meandering, convoluted language, and she kept losing the thread. It was also a bit depressing, because A.E. seemed resigned, wistful, despairing, rather than his usual feisty, cantankerous self in this book, so she closed it up. “A.E.,” she said. “Poor little A.E.”

She had yet to make another entry in her Language Arts journal, which had to be turned in on Friday. She dug around a bit in her underbed boxes and managed to locate the Emily File. She flipped through the sheets briefly: she hadn’t looked at them for several years, and the drawings were not quite as wonderful as she remembered them. Monsters, horses, aliens, buildings on fire, motorcycles, amateurishly drawn. It might still be possible to find something to use, but she lacked the energy to sort through it all just at the moment, so she closed it up and set it aside.

Andromeda decided she should try to do at least

some

homework, seeing as she was stuck at home and everything, so she opened the journal and tried to write a description of the magical landscape she had experienced earlier that day, but she found she had no words to describe it. You would have to be a poet or a great artist to capture it, it was so beyond the ordinary, which made her think of William Blake, who consciously experienced multiple planes at once and who had been a pioneer in the production of personal magic-talismanic books. The library had a beautifully printed copy of the

Book of Urizen

, and she was positive that Sylvester Mouse and the “Friends” of the Library had designs on it. She sighed. She didn’t see how she could function without the IHOB’s occult collection, and it was being relentlessly gutted. Thank gods she had her own copy of Agrippa’s

Three Books of Occult Philosophy

, at least. Theoretically, the whole of Western occultism, were it ever to be forgotten, could be reconstructed from Agrippa,

True and Faithful

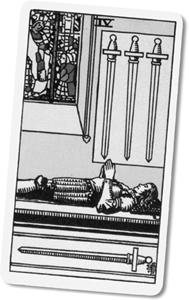

, the tarot, and

Sepher Yetzirah

. That was how the Golden Dawn had done it, adding Egyptian trappings. But Andromeda would really rather have the whole library even so.