Animals and the Afterlife (45 page)

O

FTEN, IT SEEMS

, humans argue tirelessly over philosophical reasons as to why animals do or do not have souls. If we would ask the

animals,

rather than each other, perhaps we would receive more straightforward answers. In addition to animal communicators learning the answers from animals, people from all walks of life have had similar experiences.

Regina Fetrat shared the following story about a beloved parrot:

I had a parrot named Passion until she flew away in a park on Long Island. I loved her very much and still miss her.

While Passion was with us, my husband and I used to discuss the soul existence of animals. He argued that proof of animals not having souls (and the alleged proof humans do) is that humans have the mental capacity for abstract thought and that art is the proof of this; animals do not produce art and humans do (of course, bah humbug!). Well, we would discuss this in our little bathroom. Now, there was another occupant in the bathroom. I had given Passion a towel cabinet with a few towels for nesting, and she liked to dance on the shower curtain and watch herself in the medicine cabinet mirror while she did. She loved it when we ran the shower.

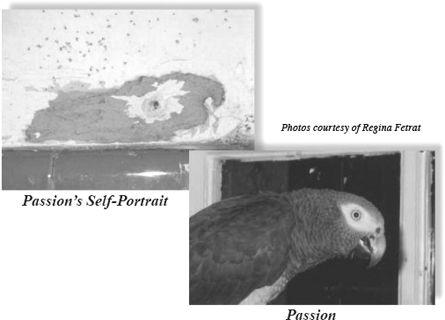

So … right around the time when these “soul proof” discussions began, Passion began carving in the wall at the end of the shower curtain rod. It was weeks after Passion was lost and gone before I realized what she was doing: a self-portrait. I cut the piece out of the drywall and still have it and photos of her just as she saw herself in that mirror.

[See photos, next page.]

Shown here is a photo Regina took of Passion’s self-portrait, along with a photo of Passion herself. (Incidentally, Regina’s husband noticed the portrait first but didn’t say anything until Regina later noticed and mentioned it!) The thing I find so interesting about the picture that Passion carved in the wall is that it does, indeed, strongly resemble the side of Passion’s face as she would have seen herself in the mirror (her eyes are on either side of her head, so she wouldn’t have seen her face head-on as a human would). Although the proportions aren’t completely accurate, all of the major details are there—the curve of the beak, the white circle around the eye, and even the pupil. Mind you, this was done with her beak! I know a lot of

humans

who can’t draw that well with a pencil—and certainly not if they were holding the pencil in their mouth!

“All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as self evident.”

—A

RTHUR

S

CHOPENHAUER

After researching this subject for many years now, I feel that the incredible amount of evidence of animal souls provides long overdue reassurance to those of us who love animals. But more than that, it sheds light on the necessary leap that must be made, from a purely logical standpoint, from a belief system that accepts the existence of

human

souls to one that includes all living beings. (Interestingly, the Latin word for soul is “anima.”)

So, what does the idea of animal souls really mean? It is extremely important that we use this new understanding

not

to justify animal abuse (just as the promise of a better life in Heaven was once used to justify the enslavement and abuse of other humans here on Earth), but rather, to hold animals in the same light as we hold humanity. They are, after all, our spiritual brothers and sisters, and once the costumes are removed, we are all of the same essence. I feel that this understanding holds the key to furthering our spiritual progress and to co-creating a more harmonious world.

Our task must be to free ourselves by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures.

—A

LBERT

E

INSTEIN

O

VER THE YEARS

, I’ve discovered that I can tell a lot about a person based on how they feel about animals—not necessarily whether they rescue animals or have companion animals themselves, but rather, their

attitudes

toward animals. I spent many years in the nutrition field, and although I met many wonderful people along the way, the overriding climate of that industry, like so many, was one of self-interest. It was a mentality of “What’s in it for me?” I watched as large groups of people flocked from one trend to another, never paying any mind to the impact of their new fad diet or supplement on the environment or on the animals who suffered in the process.

Over time, Jameth and I discovered quite unexpectedly that we could actually tell a lot about the work ethic, honesty, commitment, and quite often, the long-term outlook of any prospective employee based on their level of compassion toward animals. We have found it to be a valuable clue as to their overall integrity in

all

aspects of life.

If you have men who will exclude any of God’s creatures from the shelter of compassion and pity, you will have men who will deal likewise with their fellow men.

—S

T

. F

RANCIS OF

A

SSISI

When I transitioned from my career in nutrition to my work on this book and other animal-related projects, I was delighted yet not surprised at the level of compassion of this new group of people I now surrounded myself with: those in the fields of animal care, animal welfare, animal rights, and animal rescue. The overriding climate of this group of people is one of caring, and their ethics spill over into all areas of their lives and their work. I find that this group of people, as a whole, refuses to run from trend to trend based on self-interest, but rather, remains steadfast in their principles and their commitment to helping those in need,

regardless

of species.

I have come to understand that those who dedicate themselves to making a positive difference in the lives of animals are taking part in extremely important work in our world. This field of work does not hold a very high ranking in our world’s current list of priorities, but it is looked upon

very

highly in the spirit world, more so than most people probably realize. I feel honored to surround myself with those who are taking great strides in making our world a better place for

all

—including those who speak a language most of us do not yet understand.

One such person is Brenda Shoss, a wonderful woman who directs Kinship Circle, an international mail list and Website. The Kinship Circle mail list generates letter campaigns to legislators, businesses, and media to provoke social, political, and ethical reforms for all animals. Brenda has also written many wonderful articles, including the one that follows. I felt it appropriate to include here, and she graciously gave me her permission to do so.

Inner Landscapes: The Emotional Voice of Animals

by Brenda Shoss, Director, Kinship Circle Letters for Animals, Articles & Literature Missouri

9/11/01: A

T

8:45

A.M

. American Airlines Flight 11 smashes into the north tower of the World Trade Center. Fifteen minutes later United Airlines Flight 175 shatters the south tower and irrevocably seizes a nation’s invulnerability. Amid a frantic tangle of survivors and rescuers, Salty leads Omar Rivera from the 7lst floor to safety. On the 78th floor, Roselle steers Michael Hingson toward an emergency exit. Another dog shepherds his blind guardian down 70 flights of stairs, as glass fragments rain from the crash site above them.

If Roselle, Salty and roughly 300 other courageous canines at Ground Zero could speak, they might have explained: “It’s our basic nature. Bravery? I don’t know … How about a treat?”

Anyone who has witnessed an animal’s selfless valor knows first-hand that nonhuman beings exhibit an elaborate range of psychological, perceptual, behavioral, personal and communal initiative. “It is clear that animals form lasting friendships, are frightened of being hunted, have a horror of dismemberment, wish they were back in the safety of their den, despair for their mates, look out for and protect their children whom they love,” writes Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson in

When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals.

“They feel throughout their lives, just as we do.”

And sometimes they organize. Consider, for example, the thirty monkeys that raided a police station in India to emancipate an orphaned relative. The baby, found clinging to a female langur shot with an airgun, continued to suckle his dead mother in captivity. Meanwhile monkeys atop the station’s roof dispatched several liberators to claim the orphan. “It was as if the monkeys had made up their minds to take charge,” Inspector Prabir Dutta said. “The monkeys impressed us with their show of solidarity. Human beings have a lot to learn from them.”

Scientists and philosophers have long debated the issue of consciousness in animals. Descartes viewed them as automated entities limited to involuntary instinct. Voltaire argued that animals share our emotional fabric and experience fear, pleasure, rage, grief, anticipation, hope, and love. In 1872 Charles Darwin refuted the 19th-century code of human superiority over animals in his groundbreaking work,

The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals.

Darwin found that the ability to vocalize is merely one form of communication.

Some animals purposefully inflate hair, feathers, and other appendages when afraid or angry. To intimidate intruders, an apprehensive hen ruffles her feathers and reptiles puff their bodies into jumbo proportions. A dog’s assorted ear angles articulate curiosity, surprise, or concentration.

Does body-talk prove that animals speak and feel through myriad channels? Darwin searched for confirmation that animals weep, but found inconclusive evidence that elephants cry under great duress. Still, Masson contends, “tears aren’t grief; they’re only symbols of grief. We have to look at animal expressions of feeling on their own terms.”

Grief and an awareness of loss are regarded as human trademarks. Yet when a mother witnessed the brutal drowning of her three-week- old calf on the banks of the Elk River in Missouri last summer, she frantically guarded her dying child until authorities removed her. The traumatized cow grew paranoid around humans. “We may have to put her down if things don’t change,” her caretaker reported.

A mother’s love crosses the species barrier. Darwin recorded the unceasing calls of parents in search of lost or abducted young ones. “When a flock of sheep is scattered, the ewes bleat incessantly for their lambs, and their mutual pleasure at coming together is manifest.”

Kinship brings comfort and joy. When ties are severed, humans encounter sadness and a sense of their own mortality. So do chimps and elephants. In the PBS Nature series,

Inside the Animal Mind: Animal Consciousness

, both animals display grief when relatives die: “Elephants even linger over the bones of long-dead relatives, seeming to ponder the past and their own future.”

If animals value interconnected lives, how do we reconcile their systematic isolation and “murder” inside the slaughterhouse, fur farm or research laboratory? This is an odd conundrum that contemporary scholars seem more inclined to embrace than biologists. Plainly, the pig who confronts his killer is terrified. He trembles beneath the crushing blast of an imprecise stun gun and screams with human likeness when the knife enters his flesh. The pig’s squeal of anguish differs from the grunt of pleasure after a good meal or roll in the mud. He wants to live; “the only difference is that [animals] cannot say so in words,” Masson asserts.

In August, 2000 a six-month-old calf escaped from a Queens, New York slaughterhouse. After hundreds of pleas to save the bewildered runaway, “Queenie” arrived safely at Farm Sanctuary, a non-profit shelter in Upstate New York. Enterprising and decisive—what some might call a “tough broad”—Queenie had made an independent decision to flee a bleak situation.

The emotional voice of animals is astonishingly vast, an inner landscape shaped with perception and inclination. “The warmth of their families makes me feel warm,” writes scientist Douglas Chad- wick in reference to his time among elephants. “Their capacity for delight gives me joy. If a person can’t see these qualities, it can only be because he or she doesn’t want to.”

ANIMAL ANTHOLOGY:

ASTOUNDING STORIES

by Brenda Shoss

IN THE WORDS OF KOKO