Annapurna (39 page)

Authors: Maurice Herzog

‘What do you think of our national anthem?’

‘Oh … magnificent, and very moving for us Frenchmen …’

At that moment the Marseillaise rang out. We were all surprised

and

deeply touched to hear it in a country so remote from our own. The performance must have involved laborious practice.

We all fell silent, and the Maharajah bade us a last farewell. We saluted him respectfully and entered our cars. The dignitaries were ranged on the steps on either side of the great staircase. Orders were given, and the cars moved slowly off, while the Marseillaise was played a second time.

That evening the others dined at the British Embassy and sent off a friendly message to Tilman, who was then in the Annapurna region. Next day after a well-earned rest we visited one of the ancient capitals, Bhadgaon, where we found some Hindu temples whose splendour never ceased to astonish us. In the centre of Katmandu, in the square beside the temple, we admired a statue of Kali the Goddess. The others went to see the renowned Buddhist

stupa

1

at Swayambhonath, crowned with a tower made of concentric circles of metal.

The next day, July 12th, we left Katmandu, and according to custom, on leaving the rest-house we were each hung round with a magnificent garland of sweetly scented flowers. The Maharajah, who was full of thoughtful attentions, had ensured that my return should be effected without discomfort or fatigue, and I was borne on a very comfortable kind of litter carried by eight men. The all-too familiar jerky movement began again as we wound up towards the pass.

G. B. accompanied me as far as the first bend. He had served us most loyally and as an expression of my personal appreciation I made him a present of my revolver which, during all the war years, had never left my side. It is an unknown weapon in these parts and he was deeply touched by this memento, which for the rest of his life would remind him of our joint adventure.

G. B. could not bring himself to leave me. He saluted me with great emotion, walked beside me for a time, and then gradually dropped behind. The path wound up towards the hill and was soon lost in the jungle. The garland of flowers spread its scent around me. G. B. wore an expression of infinite sadness and the tears ran down his brown face. I looked at the mountains in the blue distance. The great giants of the earth were there assembled in all their dazzling beauty, reaching up to heaven in supplication.

The others were far ahead. The jolting began again, bearing me away from what would soon be nothing but memories. In the gentle languor into which I let myself sink, I tried to envisage my first contact with the civilized world in the homeward-bound aeroplane, and the terrible shock of landing at Orly and meeting family and friends.

But I could never have imagined the violent emotional shock that I should in fact experience when it came to the point, nor the sudden nervous depression which would then take hold of me. Those surgical operations in the field, the sickening butchery that shook even the toughest of the natives, had gradually deadened our sensibilities, and we were no longer able to judge the horror of it all. A toe snapping off and chucked away as a useless accessory, blood flowing and spurting, the unbearable smell from suppurating wounds – all this left us unmoved.

In the aeroplane, before landing, Lachenal and I would be putting on fresh bandages for our arrival. But the minute we started down that iron ladder, all those friendly eyes looking at us with such pity, would at once tear aside the masks behind which we had sheltered. We were not to be pitied – and yet, the tears in those eyes and the expressions of distress, would suddenly bring me face to face with reality. A strange consolation indeed for my sufferings to have brought me!

Rocked in my stretcher, I meditated on our adventure now drawing to a close, and on our unexpected victory. One always talks of an ideal as a goal towards which one strives but which one never reaches. For every one of us, Annapurna was an ideal that had been realized. In our youth we had not been misled by fantasies, nor by the bloody battles of modern warfare which feed the imagination of the young. For us the mountains had been a natural field of activity where, playing on the frontiers of life and death, we had found the freedom for which we were blindly groping and which was as necessary to us as bread. The mountains had bestowed on us their beauties, and we adored them with a child’s simplicity and revered them with a monk’s veneration of the divine.

Annapurna, to which we had gone empty-handed, was a treasure on which we should live the rest of our days. With this realization we turn the page: a new life begins.

There are other Annapurnas in the lives of men.

1

Monument to the dead, enclosing the ashes or relics of the Buddha, or else simply a memorial.

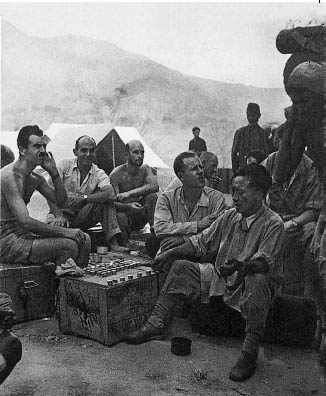

At Tansing, April 11th 1950

Angtharkay pays off the porters

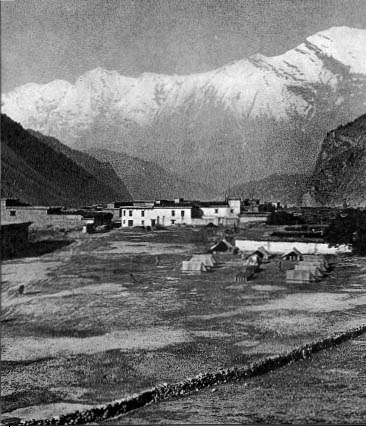

Tukucha, headquarters of the expedition

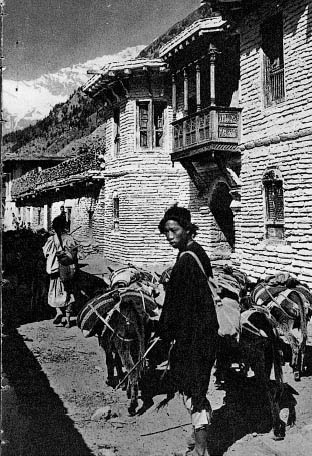

Houses in Tukucha

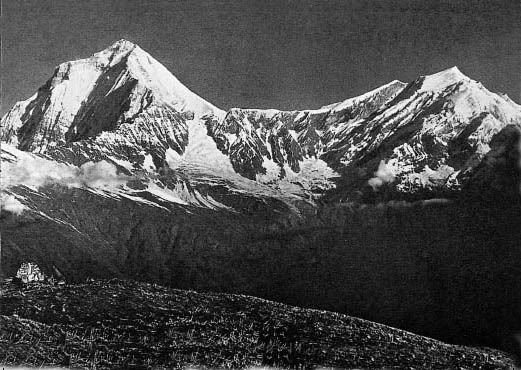

Dhaulagiri and Tukucha Peak from the east

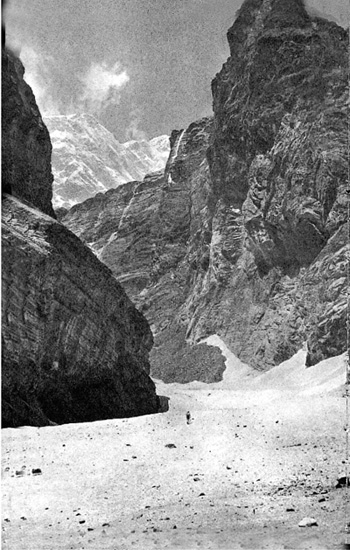

First reconnaissance in the Dambush Khola, north-east of Dhaulagiri

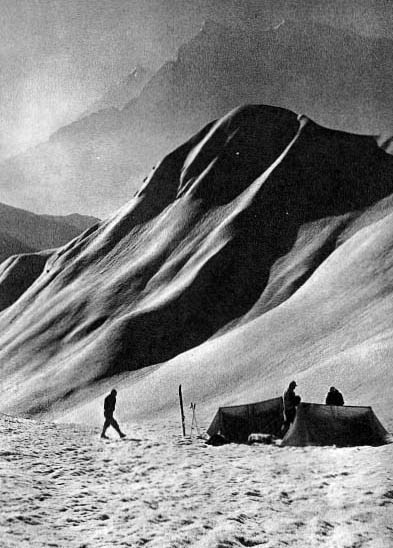

Camp high up in the valley of the Dambush Khola: The Nilgiris in the background

15,000 feet up, Herzog catches sight of Annapurna, on the right of the photograph

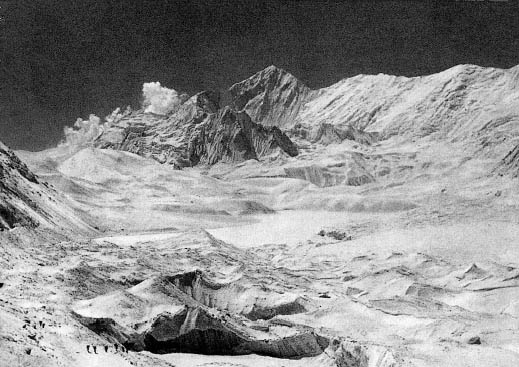

The Great Ice Lake on the Tilicho Pass, with Ganga Purna in the background