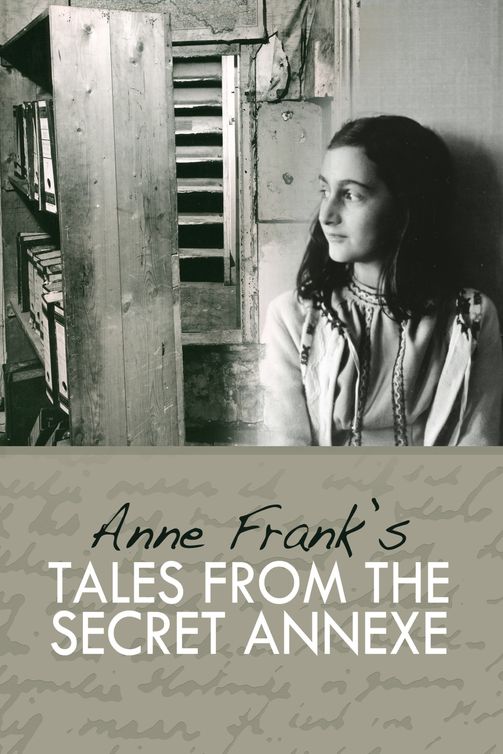

Anne Frank's Tales from the Secret Annex

Read Anne Frank's Tales from the Secret Annex Online

Authors: Anne Frank

TALES FROM THE

SECRET ANNEXE

Edited by

Gerrold van der Stroom and Susan Massotty

Translated from the Dutch by

Susan Massotty

In early 1944 Anne Frank was listening to a radio broadcast from Gerrit Bolkestein, Minister for Art, Education and Science in the Dutch government in exile in London. He announced that when the war was over he wanted the Dutch people to send in written accounts of the suffering they had endured during the Nazi occupation. This gave Anne Frank a purpose and she determined that one day her work would be published. Straight away she began the task of re-writing and editing her diaries and stories. In 1947 a first edition of

The Diary of a Young Girl

was published. Since that time the diary has not been out of print. The latest, definitive, 60th anniversary edition published by Penguin Books is also translated by Susan Massotty.

At times Anne Frank wrote more than one description of an aspect of life in the Secret Annexe: one would go into her diary and others, sometimes with minor variations, were written in notebooks or on sheets of paper. This latter work is collected together in

Tales from

the Secret Annexe

. Those tales which also appear as diary entries are: Was there a Break-in?, The Dentist, Sausage Day, Anne in Theory, Evenings and Nights in the Annexe, Lunch Break, The Annexe Eight at the Dinner Table, The Best Little Table,

Wenn Die Uhr Halb Neune Schlägt

â¦, A Daily Chore in Our Little Community: Peeling Potatoes, Freedom in the Annexe and part of Sundays.

Tales from the Secret Annexe

also includes twenty-eight further short stories, reminiscences and compositions. Anne Frank began to write a novel,

Cady's Life

, and that also appears in this edition. (Although she never finished the novel, she sketched the remainder of the plot in her diary entry of 11 May 1944.) Three further undated fragments were written on loose sheets of paper and these have been inserted before the final, very moving piece, in this revised edition of a work which should never have been allowed to go out of print.

Â

November 2010

Following the liberation of Auschwitz and at the end of a long and arduous journey, Otto Frank reached Amsterdam on 3 June 1945. He knew that his wife Edith had died in the camp but hoped that he would find his two daughters, Margot and Anne, alive.

Twelve years earlier, Hitler had become the German Chancellor. Like so many Jews, Otto Frank had known that he must get his family out of Germany but his application for visas was unsuccessful. At the time his brother-in-law, Erich Elias, was working for Opekta, a company which distributed a pectin-based preparation used in jam making. When the decision was made to open a branch in the Netherlands, Erich Elias suggested that Otto Frank lead the expansion. The Frank family moved to Amsterdam in 1933 and for a time life treated them well.

Any sense of safety disappeared when the Germans marched into neutral Holland in May 1940 and the deportation of the Jewish population commenced. In the spring of 1942 Otto Frank began to prepare a hiding place

in the upstairs rooms at the back of the Opekta building and, on 6 July 1942, the Franks moved in to what was to become known as the Secret Annexe. They were soon joined by Hermann van Pels, an employee, his wife Auguste and their son Peter, and by Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist, whom Anne called Albert Dussel in her writings (Dussel means ‘nincompoop’ in German). Her family apart, Anne also gave new names to the others hiding in the Annexe: Hermann, Auguste and Peter van Pels became Hermann, Petronella and Peter van Daan.

For more than two years the Annexe remained safe thanks to the kindness and bravery of Opekta’s office employees as well as to the extraordinary ability of the occupants to cope with the isolation and the increasing fear that they would be discovered. During the day silence was vital at all times, apart from a short break when the workforce downstairs had lunch. Then, and after the working day was over, Victor Kugler would visit, bringing news of the outside world, as well as books and magazines. A friend and colleague of Otto Frank, Victor Kugler approached Opekta’s accounting in an imaginative way and was thus able to buy ration coupons on the black market to help feed and clothe those in the Annexe.

Johannes Kleiman, another colleague, also visited regularly and provided moral support. Miep Gies and Bep (Elisabeth) Voskuijl, both secretaries, bought extra food and clothing and Miep gave Anne her one and only pair of high-heel shoes. Every evening Bep would join those in the Annexe for dinner. Seeing a need for something new she arranged correspondence courses in shorthand

and Latin for Margot and Anne. Others also formed part of the lifeline: Miep’s husband Jan provided forged ration cards and for as long as they could, a butcher and a greengrocer supplied meat and fresh vegetables.

From the time she began to keep a diary and compose stories, Anne Frank kept her work away from the eyes of the adults. On one of Miep’s visits to the Annexe, Anne was writing. She glanced up as Miep walked in with ‘a look on her face at this moment that I’d never seen before. It was a look of dark concentration, as if she had a throbbing headache. This look pierced me and I was speechless. She was suddenly another person there writing at the table… It was as if I had interrupted an intimate moment in a very, very private friendship.’ (

Anne Frank Remembered

, 1982).

Who betrayed the eight people in hiding is not known. At mid-morning on 4 August 1944 an SS officer drove along Prinsengracht and stopped outside the Opekta building. With him were members of the Dutch Security Police. A gun was pointed at Miep and she was told to stay where she was. After a search the entrance to the Annexe was found. Otto Frank and his family, the van Pels family and Fritz Pfeffer were arrested and later transferred to Westerbork transit camp in north Holland. On 3 September 1944 they were part of the last transport to leave Westerbork for Auschwitz.

Victor Kugler and Johannes Kleiman were also arrested. They were first taken to Gestapo headquarters for interrogation and then on to Amersfoort transit camp. Johannes Kleiman was so ill by that time that he was

released after intervention by the Red Cross. Victor Kugler was moved to a labour camp in Zwolle and then to another in Wageningen. In March 1945, while he was being marched to Germany with other forced labourers, the allies attacked from the air and in the confusion he escaped into a field and was hidden by a farmer. He made his way back home but after a difficult time with work, he and his wife eventually settled in Canada.

Following the SS raid on the Annexe, Miep and Bep found Anne’s diaries and papers strewn across the floor. Miep gathered everything together and tucked it away in her office desk. Two months after his return from Auschwitz, Otto Frank received a letter confirming that Margot and Anne were dead. Miep was with him and could find no words of comfort. It was then that she remembered the diaries and Anne Frank’s stories, and she handed them to Otto Frank.

M

OTHER,

F

ATHER,

M

ARGOT

and I were sitting quite pleasantly together when Peter suddenly came in and whispered in Father’s ear. I caught the words ‘a barrel falling over in the warehouse’ and ‘someone fiddling with the door’.

Margot heard it too, but was trying to calm me down, since I’d turned white as chalk and was extremely nervous. The three of us waited. In the meantime Father and Peter went downstairs, and a minute or two later Mrs van Daan came up from where she’d been listening to the radio. She told us that Pim

*

had asked her to switch it off and tiptoe upstairs. But you know what happens when you’re trying to be quiet – the old stairs creaked twice as loud. Five minutes later Peter and Pim, the colour drained from their faces, appeared again to relate their experiences.

They had positioned themselves under the staircase and waited. Nothing happened. Then all of a sudden they

heard a couple of bangs, as if two doors had been slammed shut inside the house. Pim bounded up the stairs, while Peter went to warn Dussel, who finally presented himself upstairs, though not without kicking up a fuss and making a lot of noise. Then we all tiptoed in our stockinged feet to the van Daan family on the next floor.

Mr van D. had a bad cold and had already gone to bed, so we gathered around his bedside and discussed our suspicions in a whisper.

Every time Mr van D. coughed loudly, Mrs van D. and I nearly had a nervous fit. He kept coughing until someone came up with the bright idea of giving him codeine. His cough subsided immediately.

Once again we waited and waited, but heard nothing. Finally we came to the conclusion that the burglars had fled when they heard footsteps in an otherwise quiet building. The problem now was that the chairs in the private office were neatly grouped round the radio, which was tuned to England. If the burglars had forced the door and the air-raid wardens were to notice it and call the police, that would get the ball rolling, and there could be very serious repercussions. So Mr van Daan got up, pulled on his coat and trousers, put on his hat and cautiously followed Father down the stairs, with Peter (armed with a heavy hammer, to be on the safe side) right behind him. The ladies (including Margot and me) waited in suspense until the men returned five minutes later and told us that there was no sign of any activity in the building. We agreed not to run any water or flush the toilet; but since everyone’s stomach was churning from all the tension,

you can imagine the stench after we’d each had a turn in the lavatory.

Incidents like these are always accompanied by other disasters, and this was no exception. Number one: the Westertoren bells stopped chiming, and they were always so comforting. Plus Mr Voskuijl

*

left early last night, and we weren’t sure if he’d given Bep the key and she’d forgotten to lock the door.

Well, the night had just begun, and we still weren’t sure what to expect. We were somewhat reassured by the fact that between eight-fifteen – when the burglar had first entered the building – and ten-thirty, we hadn’t heard a sound. The more we thought about it, the less likely it seemed that a burglar would have forced a door so early in the evening, when there were still people out on the streets. Besides that, it occurred to us that the warehouse manager at the Keg Company next door might still have been at work. What with the excitement and the thin walls, it’s easy to mistake the sounds. Besides, your imagination often plays tricks on you in moments of danger.

So we lay down on our beds, though not to sleep. Father and Mother and Mr Dussel were awake most of the night, and I’m not exaggerating when I say that I hardly got a wink of sleep. This morning the men went downstairs to see if the outside door was still locked, but all was well!

Of course, we gave the entire office staff a blow-

by-blow

account of the incident, which had been far from pleasant. It’s much easier to laugh at these kinds of things after they’ve happened, and Bep was the only one who took us seriously.

Note: The next morning the lavatory was clogged, and Father had to stick in a long wooden pole and fish out several pounds of excrement and strawberry recipes

*

(which is what we use for toilet paper these days). Afterwards we burned the pole.

Wednesday evening, 24 March 1943