Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (75 page)

Read Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life Online

Authors: Susan Hertog

“This dog is like a husband,” she says with a laugh. “There are good things about living alone. Nothing to push against. You can take walks whenever you want, do what you want. And yet”—the twist of logic is one only the long-married can know—“at night, under the stars, I feel closest to Charles.”

Suddenly, as if remembering something important, she gets up and goes to her bedroom. I hear her rummaging through papers. She appears with a postcard in her hand and slaps it down in front of me. It is a picture of the statues of men of the Reformation—Calvin and his followers—in the park in Geneva. They are stern, Bible-carrying figures. It is as though she has freed a long-buried feeling. For the moment, her sadness is gone. “Look at these people. They are so grim. This,” she says in anger, “this is my heritage … There is nothing beautiful about the Presbyterian Church. There is so much emphasis on sin and self-control.”

Obviously tired, she excuses herself and offers to drive me to the station at Vevey. As we leave, she pauses and points to the mantelpiece. “Do you see?” she says proudly. “I’ve arranged the flowers you brought me.”

I admire her handiwork, remembering the words of her contemptuous critics. “It’s the only art I have,” she says, her eyes sad and haunted.

A

ll her life Anne wanted to be a saint—a selfless, disembodied, servant of God. But her standard of sainthood taught her the wrong lessons. She felt tainted and corrupt, as though being human were not enough. Her biggest fear was that she was Bette Davis in disguise—a castrating selfish woman parading as a Quaker maid. But if she dueled like Davis in her dreams, her “sins” had the touch of passivity. Yes, Anne must be held accountable for the stances she didn’t take and the words she didn’t say, but she spent her whole life begging God for forgiveness and never made peace with herself.

But those of us who follow have a lens to her life beyond her own. Every day she dove down into the blackest gorges and every day she soared out again. Flying blind through the pain, the guilt, and the fear, she climbed like an eagle over the highest mountains. Her diaries, essays, novels, and poems were relentless acts of heroism in search of the “truth.” They are her moral journey into enlightenment and her long-sought vehicle of grace and salvation.

Had she only written

Gift from the Sea

, it would have been enough.

Finally, she had found the courage to stand apart and to speak her mind according to her vision. At a time when women were constrained by social mores, Anne broke through to something real, giving millions of women a deeper understanding of their commitment as wives and mothers and the courage to live independent and creative lives.

I

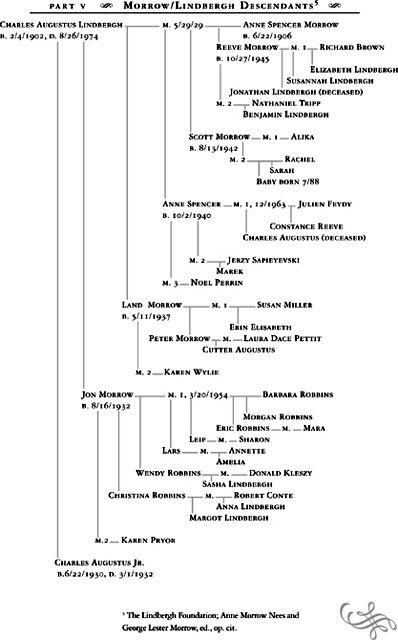

n January 1991, Anne suffered a stroke. She is no longer able to live alone or to travel long distances from her Connecticut home, so her children built a replica of her Vevey chalet in the foothills of northern Vermont. There she lives part-time with her daughter Reeve. Anne Jr. died in 1993 at the age of fifty-three from melanoma, but she is visited by Jon, Land, and Scott, and by her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She seems to move in and out of consciousness, sometimes lucid and sometimes removed. At first she was overtaken by anger—involuntary surges of rage. Ironically, her stroke had set her free from a life lived in homage to self-control.

N

ow she sits alone and quiet, content with her thoughts and her solitude, as if “pushing herself into the mind of an angel.”

3

While she remembers little of the past, and the present moves in a diaphanous blur, sometimes, as if for no reason, she recites Rilke’s poems. Perhaps Anne confirms what she has always known:

… The living are wrong to believe

in the too-sharp distinctions which they themselves have created

.

Angels (they say) don’t know whether it is the living

they are moving among or the dead. The eternal torrent

whirls all ages along in it, through both realms,

forever, and their voices are drowned in its thunderous roar

.—

RAINER MARIA RILKE

,Duino Elegies

ABBREVIATIONS:

AML: Anne Morrow Lindbergh

CAL: Charles A. Lindbergh

DWM: Dwight W. Morrow

ECM: Elizabeth C. Morrow

ERM: Elisabeth R. Morrow

CCM: Constance C. Morrow

ELLL: Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh

BMAU:

AML

, Bring Me a Unicorn, Diaries and Letters, 1922–1928

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1971.

HGHL:

AML,

Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead, Diaries and Letters, 1929–1932

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1973.

LROD:

AML,

Locked Rooms and Open Doors, Diaries and Letters, 1933–1935

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974.

F&N:

AML,

The Flower and the Nettle, Diaries and Letters, 1936–1939

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976.

WW&W:

AML,

War Within and Without, Diaries and Letters, 1939–1944

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980.

NYT: New York Times

NJSPM: New Jersey State Police Museum and Learning Center Archives All interviews not otherwise attributed were conducted by the author.

A NEW BEGINNING

1

Details of Lindbergh’s landing in Mexico are from excerpts of Elizabeth Cutter Morrow’s diaries in the Dwight Morrow Papers, Amherst College Archives;

The Literary Digest

, 12/27/27 “Lindbergh’s ‘Embassy of Good-Will’ to Mexico.”

2

Description and biographical information of Morrow throughout this chapter are based on newsreels; interviews by Edwin G. Lowry, the biographer of Morrow initially commissioned by Betty Morrow; on Harold Nicolson,

Dwight Morrow

, New York: Harcourt Brace, 1935; on Ron Chernow,

The House of Morgan

, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1990, pp. 287–301; and on the Dwight Morrow Papers in the Amherst College Archives.

3

Drawn from Ronald Steel,

Walter Lippmann and the American Century

, New York: Vintage Books, 1980; and Ron Chernow, op. cit.

4

The Campbellite Church, founded to bring unity and fundamentalist integrity to the Presbyterian Church, had become a sect that championed conservative adherence to New Testament values and straight-laced Christian virtue.

5

Dwight Morrow, “Two New Years,”

Amherst Literary Monthly, 1892–93

, Amherst College Archives.

6

See correspondence of Dwight W. Morrow and Charles T. Burnett, 1895–1903, Charles T. Burnett Papers, Bowdoin College Archives.

7

Charles Lindbergh,

Autobiography of Values

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., 1976.

8

The roof of the White House was being repaired. The temporary residence of the President was 15 Dupont Circle; from

The Saturday Evening Post

, “The Queen and Lindy,” by Irwin H. Hoover, edited by Wesley Stout, 8/11/34, vol. 207, pp. 10–11.

9

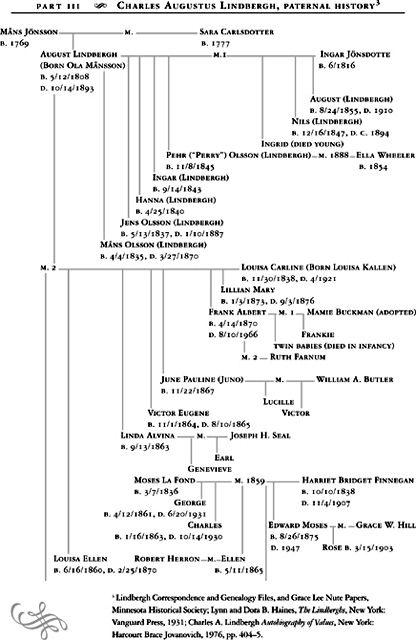

Reflecting the movement away from identifying oneself in the context of patrimonial lineage, Ola Månsson’s sons had changed their surname to Lindbergh, a contraction of the Swedish words for linden tree and mountain. Månsson adopted that name.

10

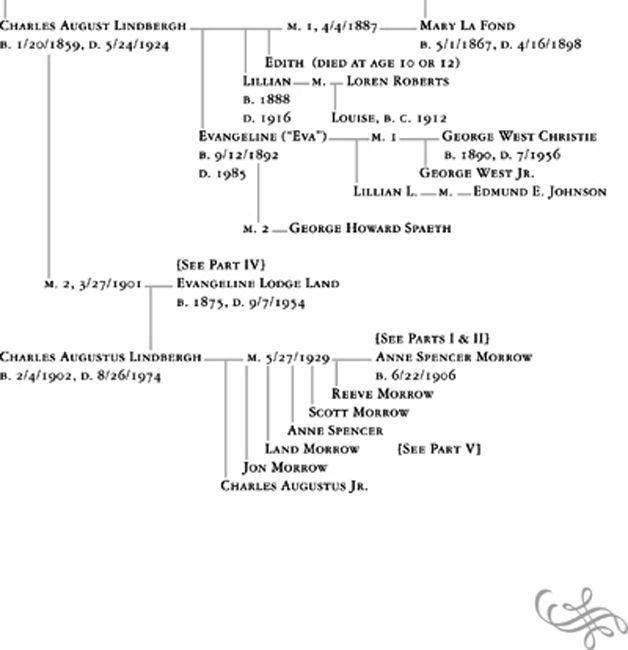

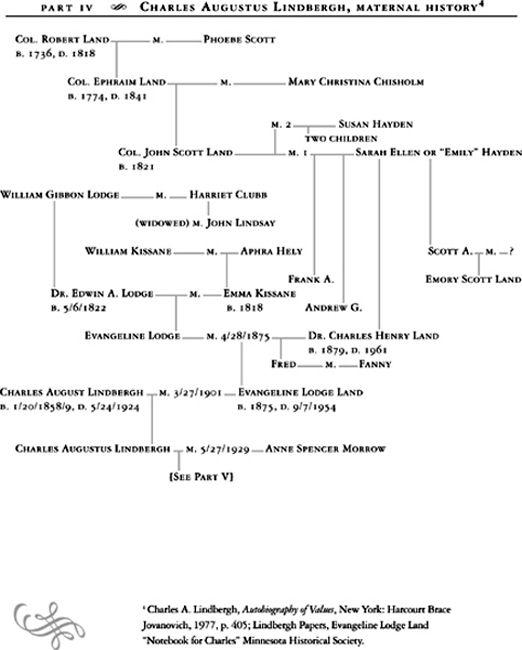

Details of the Månsson-Lindbergh ancestry and C.A.’s childhood and career are from the Lindbergh Family Papers, including a notebook by Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh that constitutes a memoir of family life until the time of CAL’s flight, marked “For Charles A. Lindbergh Jr.,” and the Lynn and Dora B. Haines papers and Dr. Grace Lee Nute’s correspondence with Charles Lindbergh, all among the holdings of the Minnesota Historical Society. Additional information from Kenneth S. Davis,

The Hero: Charles A. Lindbergh and the American Dream

, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1959; Lynn and Dora B. Haines,

The Lindberghs

, New York: Vanguard Press, 1931; Ruth L. Larson,

The Lindberghs of Minnesota: A Political Biography

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1971; and Brendan Gill,

Lindbergh Alone

, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977.

11

Haines and Nute papers, Minnesota Historical Society.

12

Paul Tillich,

The History of Christian Thought

, New York: Simon and Schuster,1967, pp.242–275.

13

Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh, Notebook “For Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr.,” Minnesota Historical Society.

14

Information about Evangeline Lindbergh’s mental state is from interviews recorded by Alden Whitman,

NYT

, and Charles Stone of the Lindbergh Museum in Little Falls, Minn. See Phyllis Chesler,

Women and Madness

, New York: Doubleday, 1972; Elaine Showalter,

The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830–1980

, New York, Penguin, 1985; V. Skultans,

Madness and Morals: Ideas on Sanity in the Nineteenth Century

, London: Routledge Kegan Paul, 1975; and Theodore Lidz and Stephen Fleck,

Schizophrenia in the Family

, New York: International Universities Press, 1985.

15

In defense of her sanity, it must be noted that Evangeline earned a master’s degree in education from Columbia University Teacher’s College after her separation from C.A. and went on to teach high school chemistry for 35 years, in both Wisconsin and Detroit, until she retired shortly before her death, in 1954.

16

Lynn and Dora B. Haines, op. cit.

17

Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh, Notebook “For Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr.;” Charles A. Lindbergh,

Boyhood on the Upper Mississippi

, St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1972; interview with AML.

18

At the turn of the century, divorce was becoming a frequent option for American women. Until then, it had been considered a byproduct of “moral turpitude and depravity.” As more women gained employment, they became less dependent on their husbands, and marriage as a financial arrangement became less attractive. Moreover, between 1869 and 1887, thirty-three states and the District of Columbia gave women control over their property and earnings. This brought about higher expectations and a lower tolerance for unacceptable behavior and conditions. Through the judicial system, these attitudes changed the interpretation of “physical cruelty,” the grounds for divorce. American marriages began failing at an unprecedented rate. Between 1867 and 1929, the population of the United States grew by 300 percent, the number of marriages increased by 400 percent, and the divorce rate rose by 2000 percent. The United States had the highest divorce rate in the world. From Elaine Tyler May,

Great Expectations: Marriage and Divorce in Post-Victorian America

, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980, p. 2.

19

L. Laszlow Schwartz, D.D.S., “The Life of Charles Henry Land (1847–1922)”

Journal of the American College of Dentists

, March 1955, vol. 24, issue 1, pp. 33–51.

20

CAL,

The Spirit of St. Louis

, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953.

21

Interview with AML.

22

CAL,

The Spirit of St. Louis

.

23

Ibid.

24

Details of CAL’s aviation career are from

The Spirit of St. Louis;

Perry Luckett,

Charles Lindbergh: A Bio-Bibliography

, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, Inc., 1986; and Kenneth Davis,

The Hero

, New York: Doubleday, 1959.

25

Irwin H. Hoover, “The Queen and Lindy,” ed. by Wesley Stout,

The Saturday Evening Post

, 8/11/34, vol. 207, pp. 10–11.

26

Dwight W. Morrow to Charles A. Lindbergh, 10/4/27, Dwight W. Morrow Papers (Series 1, box 31, Folder 47), Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College Library.

27

Biographical information about Betty Morrow is based on Elizabeth Cutter Morrow Diaries, Dwight Morrow Papers, Amherst College Archives; Morrow Family Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College Library; Constance Morrow Morgan,

A Distant Moment: The Youth, Education and Courtship of Elizabeth Cutter Morrow

, Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College, 1977;

BMAU;

and interview with Constance Morrow Morgan.

28

Interview with neighbors of the Morrows in Englewood, Joan Johnson and her mother, Mrs. David Van Alstyne, and Janet Johnson and Sue Graham, two friends of Elisabeth’s in Englewood who would become teachers at the Elisabeth Morrow School.

29

Interview with Eleanor Rodale, a friend of Anne’s at Smith College.

30

Interview with Constance Morrow Morgan and correspondence between Dwight Morrow, Sr., and Dwight Morrow, Jr., Dwight Morrow Papers, Amherst College Archives.

31

Interview with Reeve Lindbergh Tripp.

32

This section is based in part on Kenneth Davis,

The Hero;

CAL,

The Spirit of St. Louis;

and Lindbergh Papers at the National Archives, Washington, D.C.; excerpts from Elizabeth Cutter Morrow Diaries, Dwight Morrow Papers, Amherst College Archives; and newsreels from the National Archives Motion Picture, Sound and Video library.

33

CAL,

The Spirit of St. Louis

.

34

CAL,

Autobiography of Values

.

35

Ibid.

36

Elizabeth Cutter Morrow Diaries, Dwight Morrow Papers, Amherst College Archives.