Another World (16 page)

No point taking the car. He won’t dare park it anywhere, and it’s easier to go on foot. Nick cuts through the estate – deserted – then crosses the main road and runs down the slope on to the riverside path. Here the wind howls through gaps in boarded-up factories, and thrums on the barbed-wire fences that surround them. Scraps of polythene, paper, cloth, all kinds of wind-blown debris, caught on the barbs, snap as gusts of wind shake them, go quiet, snap again. Like the irregular thudding of his heart, extra systoles, little peaks and troughs of anxiety traced out on a cardiograph of barbed wire.

He’s frightened, and the more he thinks of Gareth wandering round this area at night the more frightened he gets. Gareth’s not a street-wise kid. He thinks he is, because he spends all day playing

Street Fighter

in his bedroom. He wouldn’t last five minutes with some of the kids on this estate.

Fanshawe’s empire this, shrunk to insignificance. There’s his name in blistered paint on a notice-board inside the gate. And more barbed wire. Nick’s never seen wire like it, the barbs must be six inches long if they’re an inch. Anybody trying to get through that would be ripped to shreds. Still no Gareth. He’ll just go to the end of the lane and then turn back. Sooner or later they’re going to have to face telling the police.

Nick rounds the corner and sees a child’s body lying on the ground at the far end of the lane. He breaks into a run, then slows down, heart bulging in his throat, as Gareth sits up and turns towards him.

‘Where on earth have you been?’

Gareth says nothing, just starts to cry.

Behind him the little soldier, face blank and resolute, crawls out of the circle of light into the dark.

SIXTEEN

Miranda lies stiffly under the sheets, as if she needs somebody’s permission to move. She hears Dad’s heavy steps on the stairs, followed by Gareth’s, lighter and quicker. A murmur of voices. She can’t hear what they’re saying. Something’s going on, but she can’t be bothered to get up and find out what it is.

The curtains are open, and the speckled glass glows where the moon catches droplets of rain. Miranda gets out of bed and looks out over the garden. It’s raining hard now, there’s a smell of roses and damp earth. She gulps the cool air down. It’s difficult to recapture the heat of the beach that afternoon, the hard brightness, the sharp edges of shadows on the sand.

Toiling across the sand carrying the bag, she’d become aware of a dull ache in her back. Period trying to start. Her whole body felt bloated; if you’d stuck a pin in her, water would have poured out. She was glad to sit down, though when she said she felt tired Fran snorted, ‘At your age?’

Fran’s ankles were swollen. When she dug her fingers in to show Dad they left pits in the skin that didn’t spring back into place like flesh normally does. Fran sat and watched the hollows in her flesh, while Dad fussed about with towels and the sunshade.

Miranda did what she knew she was expected to do and started to amuse Jasper, who was fractious from the heat. The little tendrils of hair on the nape of his neck and round his ears were several shades of gold darker than the rest of his hair. He was supposed to wear a sun hat, but he wouldn’t. He kept pulling it off and throwing it away. She showed him how to make a tower and stick a lolly stick in the top as a pretendy flag, but he used the stick to knock the tower down, and then cried because he hadn’t got one. Sighing, she shovelled sand into the bucket, and started again.

Dad said he was going to get ice-creams. Did she want one? Yes, she said, though she didn’t know if she wanted one or not.

A shower of sand spattered her hands. She looked up through a tangle of hair to see Gareth grinning. Fran told him to go away. He wandered off, straight-backed and mutinous, kicking sand to show he wasn’t bothered.

A minute or two later Miranda looked up the beach and saw Dad walking carefully towards them, pausing to lick the backs of his hands where the ice-cream had melted.

Miranda ate hers quickly, stuffing it into her mouth, then said casually that she thought she might go for a walk. She needed to get away from them to think and didn’t wait for a reply before setting off. There was no reason, she told herself, for her to spend the entire afternoon playing with Jasper. She was fed up with everybody assuming she liked children just because she was a girl, or that she loved Jasper just because he was her half-brother. Dad would never have left Mum if Fran hadn’t got pregnant. That’s what Mum says anyway.

The sun was hot on the nape of her neck, her armpits and groin itched, she felt heavy and sullen, as tense as those fat pods of honesty that pop the moment you touch them. She started to climb up the cliff path, hoping for a breeze. The sea was a thin glittering line, far out. No murmur of waves, but there was a constant high-pitched whine, some sort of insect, but to Miranda it seemed that this was the noise heat made.

At the edge of the path there were daisies and poppies. She picked one of the poppy heads and split the rough green outer casing open to reveal tightly furled moist petals, which she tore slowly apart. Red and wrinkled, like a newborn baby’s skin. Dad took her in to see Jasper when he was only a few hours old. The petals were sticky. She rubbed her hands and let the shreds drop.

She sat down and looked back at Dad and Fran. How far away they were and how tiny, as if she were seeing them through the wrong end of a telescope. One day, she thought, she’d remember seeing them like that. When she was old, and it was raining, she’d look back and think how happy she was today, because she was young and the sun was shining and Dad was still alive. And none of it would be true.

She stretched out, wriggling till she found a comfortable spot for her shoulder blades, and let the sun dissolve the pain.

And the next thing she remembered was hearing Jasper scream. Gareth’s got it all wrong. She wasn’t there.

It’s two o’clock before Nick and Fran go to bed, and then there’s a last-minute argument over who sleeps where. She wants to sleep in Jasper’s room. Nick says, No, she’s tired she needs her sleep.

He

’ll sleep in Jasper’s room. ‘You won’t wake up if he cries,’ she says. ‘Of course I will,’ he says. ‘I always do.’ At last she gives in. He makes up the bed, in darkness in case Jasper wakes, and crawls between the sheets. He’s exhausted. How can he not sleep?

He dozes. Once he turns to snuggle into Fran’s back, but his groping fingers reach out into emptiness. He feels the edge of the mattress, and wakes more fully. Moonlight streams through the open curtains on to the duvet, which darkens as a cloud passes over, then whitens again. Nick heaves himself on to one elbow, and sees Jasper in that typical baby position, both arms raised above his head, fists curled over on themselves.

He doesn’t want to think about yesterday, but the memories come in flashes. Gareth kicking sand into Miranda’s face, his stiff-legged defiant walk as he strode away, then slumberous darkness and peace in the patch of shade. Waking up to longer shadows and a cool breeze goose-pimpling his bare chest. No Jasper. Already afraid, staring up and down the beach. The glittering sea and the empty sands seemed to prepare a bowl of silence into which the scream fell. Running along the beach, thigh muscles pulling, feet clogged, like the worst dreams you can remember. Fran, hopelessly far behind, holding her belly in her two hands as she ran. The screams get louder as if Jasper’s coming towards him, though he can see him now and he isn’t moving, he’s lying on the ground. And then, in a rush, blood streaming down Jasper’s face into his eyes, into his open mouth. Bare chest registering wet cold and slime, fingers pushing back sticky hair, trying to see the size of the wound through perpetually welling blood. Fran comes up snatching air through a gaping mouth and takes Jasper from him. He sees Gareth climbing down the cliff face, clambering cautiously over the big rocks at its base. How pale and still his face is. The sun flashes on his glasses as he turns.

No Miranda. He can’t remember where Miranda was.

The moonlight lies on the floor as white as salt. He turns over, wrestling with the too-tight sheets until he’s pulled them loose and wrapped them round his body to form a friendlier nest. That was a good talk they had downstairs. He’s amazed at Fran. As soon as Gareth said he’d been running away to York, to his gran’s, she seemed to reach a decision. Tomorrow she’s going to ring her mother, take all three children for a day out in York, and then, if her mother agrees – and she will, she adores Gareth – he’ll stay. Of course it’s not as simple as that. There’s packing to be done, schools to visit – but in principle Fran’s taken the decision. ‘You can come home for weekends,’ she said. ‘Yes,’ Gareth replied, with no noticeable enthusiasm. Nick said almost nothing, just let them talk. He’s trying very hard not to be pleased. Alternate weekends, he thinks. They’ll do a better job with both Gareth and Miranda if they don’t have to cope with the two of them together. The reality is, somebody else will be doing the job. But that can’t be helped. He and Fran need time together with their shared children.

Sleep. He’ll go to see Geordie tomorrow. It’s only been two days, but already it feels like a long time. He needs to see him again, not for Geordie’s sake, or Frieda’s, but for his own.

Jasper snuffles and stretches, settles himself down again. Nick manages to drift off into a sleep that’s light at first, translucent, full of flashes of sunlight on water, but then, abruptly shelving, becomes heavy, dark and deep.

*

When he wakes again, he knows he’s heard a sound. He strains to listen, but there’s only the snuffly sound of Jasper’s breathing. He feels the sickness that comes from being abruptly roused from a deep sleep. He gets up and pads across to the door, goes out on to the landing, stands at the head of the stairs, looking down into the hall.

All around him the house is sleeping, muffled in a thick pelt of darkness. Fran’s snoring slightly. He hears her turn over, muttering in her sleep. ‘Jas –?’ but the name disappears into a gobble of smacked lips.

Nothing. He goes into Jasper’s room, and climbs back into bed, between the cooling sheets. He’s just about to settle down when he hears the sound again. Somewhere in the house a door opened and closed.

Footsteps climb the stairs. He waits, not moving, expecting the steps to go past, but they don’t. They stop on the other side of the door. Breathless now, he watches the handle turn.

A girl comes into the room. A girl in a long white nightdress, her hair hanging down around her shoulders. Miranda of course. After the first thud of his heart, he thinks, Who else? She doesn’t look at him, but turns and goes towards the cot.

He has to stop whatever’s going to happen next. Or rather he has to shield himself from ever knowing what it is. He says, ‘Miranda.’ She doesn’t turn to face him, even then. Moving quietly forward, he sees that her hand’s on Jasper’s face, covering his nose and mouth, not cutting off the air, more as if she’s exploring his face, trying to identify him from touch alone. Nick says again, ‘Miranda.’

She turns to face him then, her eyes wide and brilliant in the white light, but though they fasten on his face there’s no change of expression, no recognition, and with a chill of fear he realizes she’s asleep. He stares at her, tries to swallow. She seems to be aware of his presence, or at least she’s aware of somebody’s presence. ‘I didn’t do it,’ she says, her voice slurred. ‘I wasn’t there.’

He has to end this – already the moment seems to have lasted years – but he daren’t wake her. He stretches out his hands, and grips her shoulders. Only the thinnest possible layer of skin seems to cover the bone, and she’s cold. Colder than the warm September night can possibly account for. He’d have said it was impossible for him ever to feel revulsion from Miranda, but he feels it now. He takes her in his arms and presses her unyielding body against his chest.

He has to say something to close the terrible eyes. Gripping the icy flesh between his hands, he says, ‘I know you didn’t. Look at me. I know it wasn’t you.’

As he continues to hold her, the strained look starts to leave her face. Its lines soften, become more recognizably hers. He’s afraid she may wake too quickly and be shocked to find herself here, so he goes on holding her, rocking her, until the greater heaviness of her body in his arms tells him that she’s slipped into a natural sleep.

SEVENTEEN

At six-thirty the phone rings. Stumbling downstairs, Nick looks at his watch, can’t believe the time. It’s got to be Frieda, he braces himself as he snatches up the phone, expecting to hear that Geordie’s dead. Frieda shouting into the dreadful phone sounds even more panicky than she probably is. He’s not dead, but he’s had a terrible night – she’s had a terrible night. It can’t be long now. Could he possibly come over? ‘Soon as I can,’ he says. He wonders whether to wake Fran, but she needs her sleep, trailing three children round the Viking centre, then tea with her mother, then leaving Gareth behind, it won’t be easy. In the end he writes a note and leaves it propped up against a milk bottle. He’ll phone later in the morning before she goes. The streets are deserted. Something about their blankness makes him feel more tired, he’s cold, his eyelids prickle, he keeps yawning, leans forward, hugs the wheel.

Frieda’s on the doorstep in a pink dressing-gown, looking up and down the street, waiting. Arms tightly folded across her chest, her expression grudging, hyper-respectable, because she’s out here, virtually on the pavement, in full view of the neighbours, who for all she knows may be getting glimpses of her nightie.

‘He’s asleep,’ she says. She doesn’t know whether to have the doctor back to him or not.

Nick goes upstairs. He is fast asleep, two spots of colour in his cheeks, his nose sharper than before. For his nose was as sharp as a pen and a’ babbled o’ green fields… Well well.

Downstairs, Nick says, ‘Why don’t we leave it for a bit? See how he goes on.’ He makes toast and tea for both of them. When she’s finished, he says, ‘You go on up, see if you can get a bit more sleep.’ ‘I can’t sleep during the day,’ she says. ‘Never have been able to.’ ‘Well, just lie and rest.’ Reluctantly, she agrees. Five minutes later, when he goes up to check on Geordie, little whistly snores are coming from the spare room.

Nick lies on the sofa with a coat over him, saying to himself that he won’t sleep, he’ll just close his eyes. Two hours later, hearing voices, he’s struggling to sit up, his brain numbed by sleep.

There’s a confusion of stumbling footsteps at the top of the stairs, followed by a sharp cry, a yelp of pain, and Frieda’s voice saying, ‘Use the bucket, Dad.’

Nick’s up and running before he has time to think, taking the stairs three at a time. Geordie’s squatting over a yellow plastic bucket which buckles under his weight and Frieda’s bending over him, trying to support him with her hands in his armpits.

‘Didn’t make it,’ Geordie says, white-lipped.

Nick takes over, lifting him gently, helping him back on to the bed. Grandad’s trying to drag his pyjamas up, more to save the sheet than to hide his genitals.

‘Don’t worry about that,’ Nick says.

The stench from the bucket’s terrible. He fetches loo paper, soap and a flannel, and cleans and washes Geordie’s bottom, puzzled because the shit on the paper looks like tar. The only thing he’s seen remotely like it is meconium. ‘All right now?’

It’s very obviously not all right. Geordie lies curled up like a foetus, rigid with shame. He’ll die now, Nick thinks dispassionately. This is it. He’s had his bum wiped like a toddler. He’ll die now. And indeed, at that moment, with a gesture Nick can hardly believe he’s witnessing, he’d been so certain it was cliché, Geordie turns his face to the wall.

All this time Frieda’s been hovering in the doorway, wanting to help, but knowing she’s better out of it. That Nick should see Grandad like this is bad enough, but it would be worse for him to be seen by her. Only when it’s over, after Nick’s drawn back the curtains and picked up the bucket, does he realize it’s full of black digested blood.

‘Have you seen this?’

Frieda doesn’t reply, just whimpers and turns her head away.

‘That solves whether we call the doctor or not. I suppose I ought to save some of this for him to look at.’

‘Just leave it,’ she says.

‘No, it’ll stink the house out. He only needs to see a bit.’

He carries the bucket to the kitchen, finds a bowl and scoops out a sample. On his fingertips, when he’s finished, is a trace of red, mixed in with the black, but only a trace. He covers the bowl and sets it to one side to await the doctor’s arrival, then tips the rest down the loo and presses the flush. A swirl of blackness leaves the bowl startlingly clean. He washes and scrubs his hands under the hot tap, dries them on loo paper and throws the paper away. Then he goes downstairs and calls the surgery.

When he goes back, Geordie’s propped up against the pillows, their whiteness making his skin look dingy. ‘I’m not having any doctor.’

‘Too late. I’ve rung the surgery.’

‘Aw hadaway, man, there’s nowt he can do. We all know what it is.’ He subsides, muttering, ‘Complete waste of bloody time.’

He turns away, shoulders hunched, sulky as a parrot. Nick asks about the pain, gets no reply.

Downstairs Frieda’s buttering bread. ‘I don’t want anything,’ he says automatically, then thinks she needs it herself and she’s more likely to eat if he eats with her.

‘No, go on, then. We’ll probably feel better if we have something.’

They sit at the kitchen table together. Nick forces himself to take a bite and washes it down with hot sweet tea. They eat in silence. When she’s finished she wets her forefinger and reflectively picks up crumbs of bread.

‘This is it, isn’t it?’ she says.

‘Yes, he can’t survive that.’

By ‘that’ Nick means not the haemorrhage so much as the humiliating weakness, the exposure. Geordie’s a self-contained man in many ways, fastidious, particular about fingernails and underwear. Nick feels he’s never known him, not because they’ve been distant from each other – far from it – but because they’ve been too close. It’s like seeing somebody an inch away, so that if you were asked to describe them you could probably manage to recall nothing more distinctive than the size of the pores in their nose. Only now, when the proximity of death’s starting to make him recede a little, can Nick make meaningful statements about him: that he’s fanatically clean, that he minds about the state of his fingernails.

After they finish the sandwiches he goes upstairs, but Geordie’s asleep or, at any rate, has his eyes closed. Nick bends over him, trying to check from the movement of his chest that he’s still breathing. Immediately the blue eyes flicker open and he’s subjected to a bright ironical gaze that knows exactly what he’s doing and why.

‘Not yet.’

The doctor arrives mid-morning, Dr Liddle, a middle-aged man with a vaguely clerical demeanour, Scottish accent, repaired hare lip.

Nick runs upstairs ahead of him and tries to lift Grandad into a better position, but he seems to be hardly conscious, his lips move in protest, his eyes remain closed. Nick doesn’t know whether he’s getting worse by the minute or whether he’s simply decided to close his consciousness against this medical invasion. Not that this is particularly invasive. Liddle raises his eyebrows at the sample, takes Geordie’s temperature, his blood pressure, listens to his chest, feels his pulse, looks at the swollen stomach. ‘I’m not going to mess him about prodding his tummy, I can see all I need to see.’

Geordie opens his eyes at last, perhaps objecting to being spoken about in the third person. ‘It’s bleeding again, isn’t it?’ he says, pressing his hands to the old scar.

‘Ye-es, but you’ve got good healing flesh,’ Liddle says comfortably. ‘I don’t think it’ll bleed again.’

No attempt to grapple with the real cause of the haemorrhage. They humour him, all of them, but perhaps that’s what he wants. Perhaps in his own way he’s humouring them. There’s something here Nick can’t grasp. Grandad’s not a man of much formal education, certainly when forced to refer to bodily functions it’s all front passage, back passage stuff, but he’s not stupid. His belief that he’s dying of this ancient wound may be strange, but it isn’t meaningless. The bleeding bayonet wound’s the physical equivalent of the eruption of memory that makes his nights dreadful.

‘You’ll feel a bit weak for a couple of days. Take it easy. We’ll soon have you up and about again.’

Geordie seems to find this optimism consoling. He doesn’t believe a word of it, but he likes to feel the proper things are being said, a tried and trusted routine adhered to.

‘How much pain is he in?’ Liddle asks when they’re out of the room.

Nick and Frieda look at each other. ‘Surprisingly little,’ Nick says.

‘I’m inclined to leave him at home,’ Liddle says. ‘As long as you think you can manage.’

Frieda says, ‘We can manage.’

‘How long do you think he’s got?’ Nick asks.

‘Not long. Days rather than weeks.’

After seeing Liddle out, they go back upstairs and stand at the foot of the bed, looking at Geordie.

‘That went off all right,’ he says, dismissing Liddle, glad to be alone again.

Frieda tidies round, straightening the sheets. Geordie’s tolerant now, letting himself be tidied up, though he rules out shaving, he’s too tired at the moment. He’ll tackle shaving later. Then he leans back against the pillow, his eyes drooping, but not closed. Nick realizes he’s watching shadows dance on the counterpane, leaves with a blue tit pecking about in them, searching for tiny insects. He’s lying like a baby will sometimes lie in its cot, entranced by the play of light and shade.

Frieda’s searching through Geordie’s bureau for his insurance policies.

‘Have you found any?’ Nick asks.

‘Not yet, but they’ll be here somewhere. Here, look at this.’ She holds up a bundle of receipts. ‘He kept everything. Mind you, he was right. They can come back at you.’

‘Not after seven years.’

By the time he’s washed up and tidied the kitchen she’s found the policies, and sits in the armchair, clutching them, looking breathless, excited and slightly guilty. ‘I know you might think this is terrible, with the poor old soul still alive, but you’ve got to be practical,’ she says, turning pink.

‘I don’t think it’s terrible at all.’

But she’s not comfortable. Every remark about the funeral, who should be told, what Grandad’s said he wants done, has to be prefaced by copious disclaimers about not being morbid, grasping, premature, etc. ‘He went in for that thing, you know, that scheme where you sort of freeze the cost of the funeral at what it would’ve been if you’d died at the time you sign on. No matter how long you live it stays the same price.’

‘They’ll be losing money on him.’

‘No, they won’t. He’s not been in it that long.’

Grandad calls down to them. He’s woken up after a long sleep, and Frieda puts the bundle of policies to one side and goes up to attend to him.

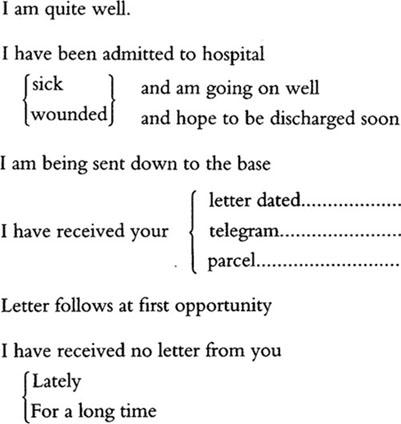

While she’s gone Nick opens a small drawer in the centre of the bureau, where Grandad keeps family snap-shots, a few letters, his birth and marriage certificates, and his field service postcards. All his letters from France have vanished over the years, but these, for some unaccountable reason, have survived.

NOTHING

is to be written on this side except the date and signature of the sender. Sentences not required may be erased.

If anything else is added the postcard will be destroyed

.

After this encouragement to economy of expression, the list of choices.

What fascinates Nick is that word ‘quite’. Does it mean ‘fairly’ or ‘absolutely’? In neither sense can it have been an accurate description of the state of the men who, in the immediate aftermath of battle, sat down, stubby pencils in hand, and crossed out the least appropriate choices.

On 2 July, ten days after Harry’s death, Geordie was ‘quite well’. He was neither sick nor wounded, he had not been admitted to hospital or sent down to base, and he had received a letter from his mother dated the 27th of June.

There are five postcards from then till the end of 1916. In each of them Geordie has crossed out ‘Lately’ so the final message on each card reads: ‘I have received no letter from you for a long time.’

On 14 April 1917, three days after he’d been bayoneted, he’s been admitted to hospital (wounded) and ‘am going on well’ (he nearly died). The address on the other side of the card has been written by somebody else, but the signature, though shaky, is his own. On that occasion too he had not heard from his mother for a long time.

It’s almost as if his mother stopped writing to him after Harry’s death, or at least wrote very rarely. Perhaps she was so shattered she found it difficult to write to anyone, but a son? And in the front line?

Me mam never got over our Harry… Wrong one died, simple as that

.

Perhaps it wasn’t ‘survivor’s guilt’ that made Geordie imagine his mother had rejected him. Perhaps it was true.

The time wagon travels backwards, pulling them away from the present. On either side figures slip past and vanish: an air-raid warden from the Blitz, an unemployed man in a cloth cap, a First World War officer, his arm raised, cheering, a lady in a crinoline, and so on until the wagon backs into the roar and crackle of flame, shouts, cries, a woman with a wounded baby in her arms, screaming. Leaving her behind, the wagon travels further back, then stops, turns, and moves forward into the light of Viking Jorvik.