Antarctica (13 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Walker

First, we stopped at a skua nest to check on the eggs. âI like skuas, too,' Olivier said. âThey're tough. They're not afraid of you. As soon as you put a ring on one of these birds, it has a personality. Some birds are shy, some are nasty, some are clever, some stupid. One skua specialises in taking off people's hats and dropping them in the sea. A friend lost a lens cap from his camera. They test everything to see if it's edible.'

On the bare rock there was one unhatched egg and one bemused-looking ball of fluff. The egg was lying in a pool of meltwater, which put it in imminent danger of freezing. Oliver climbed over and did his best to drain the water while the two parents screamed madly and dive-bombed him, their wicked beaks shining with menace. Automatically, he put one hand up in the air above his head as he crouched.

âThis pair is one of the easier ones,' he said over his shoulder. âWith the others I have to carry a stick and hold it high in the air. Then they don't attack.'

âWhy?'

âI don't know, but it works.'

âWhat makes them so aggressive?'

âWe don't know that either. You might think they had high levels of testosterone, but in fact it's pretty low. Probably because testosterone is expensive. It suppresses your immune system and down here you can't afford to get sick.'

He backed off and the mother settled on the nest, rolling the egg carefully back into the puddle of water. Olivier shrugged fatalistically and we moved on.

Now we were walking up the rocky hillside, skidding on penguin guano and slushy snow, carefully stepping over the conduits that hid the network of cables keeping the station alive. âSnow petrels have the same problem with meltwater,' Olivier said. âThere's fierce competition for the best nesting sitesâthe ones that are sheltered from snow or drain water well. The birds live forty years or more, so it's tough for young new breeders.'

Researchers had been banding both chicks and adults here since 1963. It was impossible to tell how old the adults were when they were first banded, but when they settled into a nest site you could then watch them for the rest of their lives. âThey are very faithful to the nest each year. If a bird is missing for two years it's probably dead. They don't breed elsewhere. If you destroy a breeding site, they won't breed for the rest of their lives.'

The colony was a regular bank of rocks, just like all the others, except that many of the crannies and hollows held birds. They were a little smaller than doves; their beaks, feet and eyes were black and the rest of them was snow-white.

Olivier told me that, like Thierry with the Adélies, he wanted to understand what inner hormonal signals drove the snow petrels. They, too, shared parental duties, and if their mate was late they had to make exactly the same decisions as the emperors and the Adélies. This summer, he was studying the stress hormone corticosterone to see if it played the same role here, too.

âMany other birds have a totally different strategy. Robins, say, or blackbirds, only live for a couple of years, and they lay four, five, even six eggs at a time. But all the birds here are so long-lived that their strategy is to favour their own survival over that of their chicks. A snow petrel can go five, six years without breeding. They only lay one egg and won't re-lay if they lose it. Even if no chicks survive for one year, the population can still be stable because the parents don't take risks. Their priority is their own survivalâthere will be many more chances to breed.

âWe think corticosterone is the key. But it might depend on age, too. Young breeders are very prudent. But if the older ones have only one or two seasons left in them, they might take a few more risks.'

30

He told me that the science was surprisingly easy to do here. Since good nest sites were so hard to come by, and possession was most of the law, snow petrels incubating eggs were reluctant to leave their nests for any reason. That made them easy to catch. They were so attached to the nest site, they wouldn't even try to fly away.

They would, however, fight. Young birds challenged the owners all the time for good sites. As we walked through the colony one such youth decided to try its luck. It launched itself at the nearest nest possessor with a fierce flurry of beak and wings. Now the two of them were shrieking, stabbing brutally with their beaks and scratching with their claws, grappling and rolling over each other like cage fighters egged on by a crowd.

Olivier was right. In spite of their angelic appearance, they were more vicious than the skuas. But it was about to get even worse. The owner of the nest threw back its delicate white head and

splat!

A glob of bright orange goo emerged from its beak, arched through the air and landed squarely on its opponent's back.

Splat!

There went another one, this time barely missing the recipient's eye. The poor creature was vanquished. It yielded hastily and our hero returned to its nest with something like a swagger.

These graceful birds

spit?

Olivier grinned at my shocked expression. âIt's an effective weapon for them,' he said. âThey use oil from their food to make the spit and it's bad for their feathers.' We both watched as the unfortunate recipient of those lurid orange gobs rushed off to roll on the snow and try to get clean. âSome birds can be lovely,' Olivier remarked. âWhen you lift them to check their leg ring they will gently preen your hand. Others see you and spit immediately. And the spit stinksâwhich is why we're the smelliest people on base.'

He said this cheerfully, as though it was a badge of honour. âI've kept the jacket from one winter I spent here. It still smells fourteen years later. When I'm in a bad mood at home I get it out and smell it and remember.'

Olivier was still investigating which hormones drove the snow petrels to fight, and which made them yield for the year. And he told me that emperors too could be victims of raging hormones. âFailed breeders can kidnap chicks. There can be up to five or six adults fighting over a chick and quite often the chick will die. Or they can adopt a chick for a few days and then kick it off. We think this might be because of another hormone behind parental careâprolactin. When the female emperor returns after two months, she has no idea if the incubation has been successful. So she has to have lots of prolactin to keep the urge alive. Then the male goes off foraging for a month and has to be motivated to return.'

Emperors also have an inbuilt hormonal trigger for when to quit. They will always abandon their eggs or chicks rather than risk their own lives, and of the owl-eyed chicks that crowded confidently around me yesterday, fewer than one in five will make it to adulthood. âSome emperors are more than forty years old. Like snow petrels they'll have many more opportunities to breed. It's better to fail one year but stay alive.'

It was better, in Shackleton's words, to be a live donkey than a dead lion.

That evening after dinner there was another movie showing, but I slipped out again and walked down to the sea. I diverted past one of Olivier's snow petrel colonies. They were beautiful still, and their spitting didn't make them less so. It just gave them bite.

Down by the sea there was the usual procession of Adélies, trotting down the snow paths, queuing to jump into the quiet waters and stock up on fish to feed their hatchlings. I watched them for more than an hour; the leaps looked dramatic but made almost no sound, and the whole scene was deeply peaceful. They knew what they were doing, these little beasts. No wonder they had no self-doubt. Like the Antarctic heroes of old they would battle against extraordinary odds, survive appalling conditions and push themselves to the limits. But like the emperors and the snow petrels, too, they had also inherited another important lesson from their forebears, and it was the same lesson that Shackleton had to swallow just a hundred miles from the Pole. To survive down here, you also have to know when to quit.

Eventually, my muscles stiffening, I got up and started to walk home. But I had the feeling that someone was watching me. I turned abruptly. One of the Adélies was about six feet behind me, staring up at me, motionless, unblinking. I turned again, walked a few hundred feet and then quickly looked back. The penguin had matched me step for step. It was standing there, perfectly still, six feet behind me, looking up with that same measured stare. We repeated this game once, twice, three times. It was playing statues with me. Each time I turned it was motionless. Each time I walked, it walked with me.

We were almost back at the dorm now, and it had followed me all the way. I remembered David Ainley saying that Adélies treat you as if you were an overgrown penguin, and how I thought at the time that he seemed to see himself the same way. I looked down again at this little creature and it looked unflinchingly back at me. I don't know who was anthropomorphising whom, butâthough I stepped inside the dormitory and closed the door firmlyâI knew that I had succumbed. Penguins have melted stonier hearts than mine. I never stood a chance.

3

Â

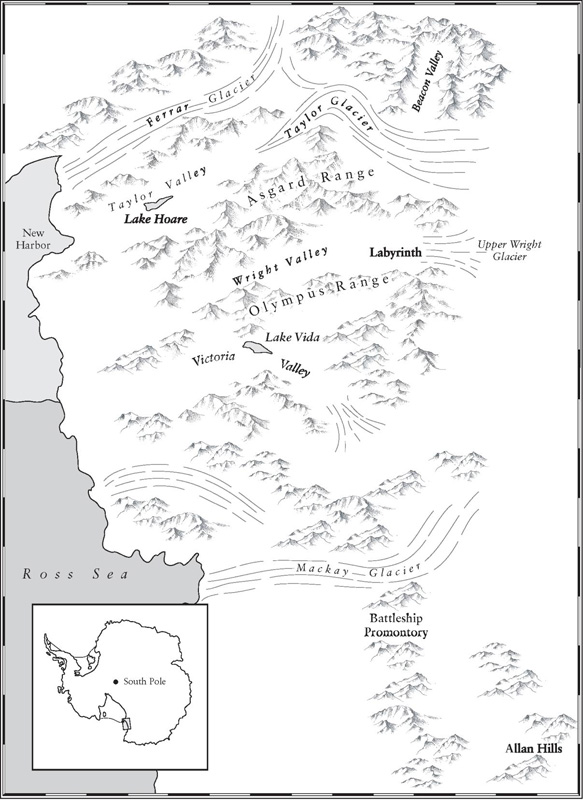

The McMurdo Dry Valleys are the closest thing we have on Earth to the planet Mars. A set of bare rocky valleys running in parallel from the edge of the ice sheet down to the sea, they are âdry' not just through lack of water, but through lack of ice. They are also all but monochrome. The jagged mountain ranges that separate the valleys are run through like a layer cake with alternate slabs of chocolate brown dolorite and pale sandstone. This is an unearthly place, intimidating and harsh in the bright light of noon. But at night in the summer, when the sun never sets but merely hovers close to the horizon and casts its long low shadows, the peaks seem to soften, the dolorite rock grows richer and the oatmeal sandstone takes on a golden glow.

It's not just the colours that look their best at night-time. Those long shadows also pick out the features that tell the history of this extraordinary place. There are weird raised beaches, jutting out halfway up the mountain sides, which mark ancient high stands of water; rock ripples and gigantic potholes that were once carved out by a waterfall the size of Niagara; and bulbous glaciers and frost-cracked soils that show how cold and dry this land has now become.

Fifty-five million years ago, Antarctica was warm, wet and brimming with life. The surface shifted and shuddered, driven by grinding tectonic forces in the crust beneath. As the crust tore, this part of the ancient world lurched upwards. And with the rising land, the rivers on its surface now had something to get their teeth into. They cut down into the raised rocks, carving out this set of parallel valleys as they surged from the interior to the sea.

Meanwhile, tectonic happenings on the other side of the soon-to-be continent were beginning to make themselves felt. After millions of years of gradually separating itself from the rest of the world's land masses, Antarctica had only one remaining point of contact: the long thin arm of the Antarctic Peninsula was still clinging on to the southern tip of South America.

And then, some thirty-five million years ago, it slipped its hold. Seas surged between the two former partners, and currents began to swirl around the new continent, building up into a vortex that cut it off from the warmth and comfort of the outside world.

The opening of Drake Passage had slammed Antarctica's freezer door shut. First its trees disappeared, then its tundra faded to dust. To the south, up on the Antarctic plateau, a mighty ice sheet advanced towards the coast. It would have swamped the valleys but a saw-toothed range of mountains, thrown up along their southern edge by those earlier tectonic convulsions, stopped the ice sheet in its tracks. Instead, the valley floors stayed bare, growing steadily colder and drier. A few small glaciers built up from snow banks on the mountains, and spilled down on to the valley floors. Cold air poured down from the plateau in the form of mighty winds that scoured and shaped the rocks, carving holes in them that whistle eerily. No rain has fallen in the interior of the Dry Valleys for millions of years, and there has been precious little snow. This is the coldest, driest, barest patch of rock on Earth.

That alone would be enough to excite many scientists. To understand our home planet, people always want to go to the extremes. But the DryValleys have something more alien to offer. For the history of this region mirrors the early history of Mars, one of our nearest, and most intriguing, extra-terrestrial neighbours. Like the Dry Valleys, Mars once had liquid water on the surface, and was possibly also warm. Its surface is still cut through with channels where water once ran, basins that were once giant lakes, and beaches that once marked out ancient seashores. Now, though, its average temperature is -67°F and it is one of the driest places in the Solar System. That's what's really special about the McMurdo Dry Valleys. At some point in its life, Mars may have passed through the same stage that they are experiencing today.

1

This is Mars on Earth.