Antarctica (35 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Walker

The reason was to get a background check, a ground truth. Satellites were spinning overhead measuring the radiation coming in from space, and the equivalent radiation being poured back out from the surface. Finding the balance between these two helps establish what our climate is actually doing. But after a while, the satellites can lose their focus; their measurements drift and they take their instrumental eyes off the ball. So researchers find certain special places, like this one, where they can measure the numbers on the ground and use them to drag the satellite readings back into line.

Dome C is particularly good for this because it's so flat. There is very little wind, which means the surface is smooth and the reading is similar regardless of the angle at which you look.

17

Perfect for Richard's purposes. He wasn't here to look for signs of change; he just wanted to be sure the satellites were telling the truth.

Here in the continent's interior, on the old, cold, dry and above all thick East Antarctic Ice Sheet, nothing much is changing or likely to change for a very long time. Whatever we do to the Earth, chances are that there will be ice on this part of the continent for thousands or tens of thousands of years.

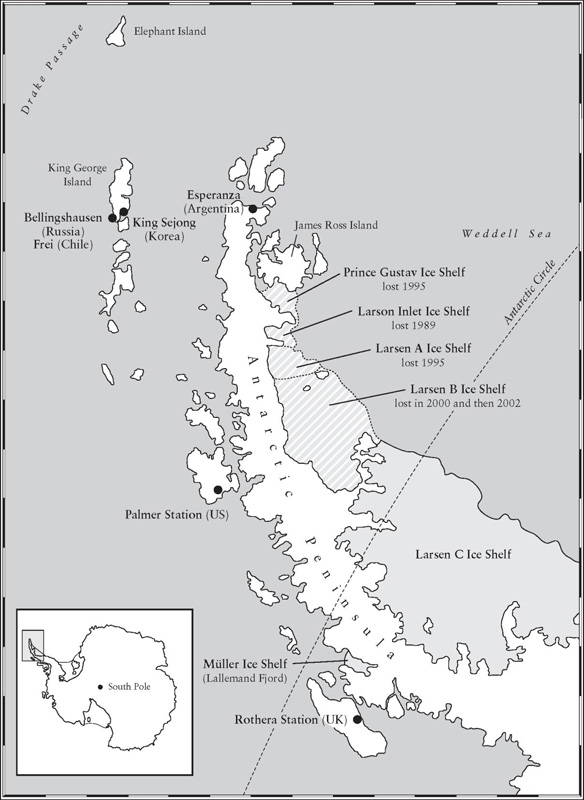

But although this part of Antarctica is set in its ways, others are starting to stir. Over in the west the ice sheet is thinner and more nimble on its feet. Gigantic glaciers speed over the ground at what is for ice a dizzying pace. The ocean is already beginning to lap at certain parts of the coast, eating away at floating ice shelves, undermining them. And the satellites that Richard helped to calibrate are showing that the Antarctic Peninsula, that great finger of land that is embedded in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and points accusingly up towards South America, is currently warming faster than anywhere else on Earth.

Â

Â

Â

Â

PART 3:

Home Truths

6

The Antarctic Peninsula is the northernmost part of the continent. It's also the most conventionally beautiful place in Antarctica. Take the Alps, and cross them with the Grand Canyon. Stretch them both so that the mountains are higher, the cliffs sheerer, the glaciers wider and longer and bluer. Now put this glorious mix beside the sea, next to icebergs and penguins and seals and whales, and all within just two days' sail of civilisation.

There you will find bright blue days or silent grey ones, when the water is eerily still. You can sail down narrow channels, only passable for a few weeks of the year, where mountains and ice plunge steeply down to the sea on either side, and researchers in field camps on the banks call up the ship's radio for the sake of a little contact with the outside world, or signal their greetings with waves or cartwheels.

It's not surprising, then, that this is also the most visited part of Antarcticaâthe human face of an otherwise inhuman continent. More than 20,000 people come here every year, most of them by sea.

1

And the voyage may be gentle or riotous, depending on nature's whim.

If you make this journey south, you will probably start off at one of three ports: Punta Arenas in Chile, Ushuaia in Argentina, or Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands, just off the Argentinian coast. These are small, remote southerly towns, whose hotels have names like âThe End of the Earth'. But they aren't, or at least not quite. It's the ice-reinforced ships that sail south from here that will take you to the real end.

At first, as you enter the Atlantic and head south, the seas will probably be calm; you'll be shielded from excessive weather by the coast of South America on the starboard side. But after perhaps half a day's sailing you will emerge beyond its protective tip, and out into the wide-open seas of Drake Passage.

This is the gap that first opened around thirty-five million years ago, when South America released its geological handhold and drifted away, and the oceans were finally free to swirl unchecked around the entire continent of Antarctica. From west to east, with no land left to stop them, they built up a vortex of currents that isolated Antarctica from the warmth of the north and allowed it to fall into a deep freeze.

That same unbroken geography also renders this stretch of ocean the stormiest in the world. Winds and waves circle the globe here with no land to break their momentum, and the Pacific and Atlantic oceans can clash with such devastating fury that Drake Passage is notorious in shipping lore. Before the Panama Canal was built, rounding Cape Horn at the bottom of South America and braving these southern seas was the fastest way to get from the Atlantic to the Pacific and also the most dangerous; in the past four centuries of sailing more than a thousand ships have been wrecked here. It is rich with mysticism and romance. On the tip of Cape Horn, beside the tiny military base, is a monument bearing the silhouette of a wandering albatross and a poem by Chilean poet Sara Vial:

Â

I am the albatross that waits for you

At the end of the Earth.

I am the forgotten soul of dead sailors

Who crossed Cape Horn from all the seas of the world.

But they did not die in the furious waves.

Today they fly in my wings to eternity

In the last trough of the Antarctic winds.

2

Â

Before you cross this boundary and sail out into the passage, you'll need to tie down or pack away everything that can move. You'll also learn what to do if the ship's alarm sounds: how to find and drag on the unwieldy, suffocating rubber immersion suits; where to gather beside the sealed melon-shaped lifeboats that will be your last resort; how not to think about what it would be like to be squashed inside one of these with twenty other humans, while the ocean tossed you about like a football.

If the winds are bad, you will understand why so much of the ship's furniture is screwed to the floor, and why the tables have wooden rims. If it's not fastened down, the chair you are sitting on can fly through the air. Waves have been known to crash so high that they smack against the windows of the bridge, sixty feet up. The only way to move around the lurching ship is to cling with both hands on to doors and railings. You will not be going outside. You will probably not be going anywhere much, just lying weakly on your bunk, holding on to the wooden sides and wishing for it to be over.

There is not much you can do to escape a bad crossing, apart from avoid tempting the fates. Superstitious sailors, which is to say all sailors, will give you a list of things not to say or do. If the rim of a glass starts ringing, stop it immediately. Don't whistle while on board, or you'll âwhistle up' a storm. Andâthis one is nicely perverseâdon't wish anyone âgood luck' as it will assuredly bring bad luck down on you all.

But if you are lucky, and the storms never come, you will experience instead one of the world's loveliest ways to travel. As the long lazy waves fetch up from the Pacific you will feel hour upon hour of rolling swell, rocking you like a cradle, like a lullaby. Once in a while a larger wave might come along, making the ship judder slightly as if she had hit a bump in a road, before resuming her gentle swaying. And if you look outside, chances are that you'll see the grey-white form of an albatross gliding serenely beside the ship.

If you have one of these crossings you will be infused with a sense of perpetual well-being, and sleep deeply and dreamlessly, however thin your mattress or narrow your bunk.

3

At some point towards the end of the second day, you will begin to sense the impending ice. It might just be a chill creeping into the air. But if it's foggy, or dark, or both, you will know there is ice out there when the captain switches on searchlights, and trains them like cannon on a point a few metres in front of the ship.

The lights are for small chunks of ice that could still make a sizeable dent in the hull: bergy bits, or, worse still, growlers, which are almost completely submerged and are much harder to spot. They're not for icebergs. By the time you saw a berg with the spotlights, you would be far too late to avoid it, and you'd also be in big trouble. They can be huge, these bergs, the size of a ship, the size of an island.

Instead the crew must count on a radar screen whose arm sweeps periodically around revealing an array of glowing green blobs. It can be eerie up on the bridge, surrounded by mist, knowing there is ice out there and yet seeing nothing. The crew will be tense, and focused, their eyes flicking constantly between screens and lights. To be allowed to stay, it's best to keep quiet; and above all, don't get between the crew and their consoles.

And then, if the day breaks and the fog lifts, you will see your first iceberg. It might be small, and irregularâa chewed-off chunk that has melted and fragmented almost all the way to oblivion. Or it might be vast, high and square, as if a granite cliff had floated into the sea. These tabular icebergs are an Antarctic speciality; they break off from the huge floating shelves of ice that rim the continent.

This is all perfectly natural, and has been happening, to some extent, since the ice was born. However, as well as being the most human part of Antarctica, the Peninsula is also currently a place of change. There are many who suspect that this segment of Antarctica is behaving like a miner's canary, feeling and responding to the trouble that may soon come for us all. Researchers and tourists alike are now flocking here: the former to find out exactly what is happening, and what it means for the rest of the world; the latter to witness this extraordinary wilderness before it changes for good.

Â

The first thing that strikes you when you reach the Peninsula is the overwhelming abundance of life. Compared to the rest of this remote and barren continent, the waters here are awash with living things. Chinstrap penguins in small, synchronised packs porpoise neatly past the ship's bow, making barely a splash as they cut through air then water then air. There are rockhopper penguins, with absurd golden feathers that sprout like fascinators from either side of their heads. And gentoos, which look like Adélies apart from the white strip that runs over their heads and ends in a white blob next to each ear, as if they were wearing iPod headphones.

Then there are the seals, of course, usually lolling motionless on passing icebergs, dark smears against the white: Weddells, and thuggish thickset leopard seals. Also crab eaters, slender and silver and bizarrely misnamed since they actually eat a smaller shrimplike crustacean called krill.

You might also see humpback whales, and if the rest of the animals are jumpy that probably means that a pod of orcas will soon be cruising past, with their boastfully tall black dorsal fins, and beady mean-looking eyes. A more charming prospect is the minke whales, the second friendliest and most curious of all the whale species around here. They don't just spout in the distance like the humpbacks; they come and play right by the ship.

The friendliest of all the whales are the southern right whales, the golden retrievers of the cetacean world. They love human company, or, rather, they did, and this unfortunate tendency led them to be hunted nearly to extinction in the early part of the twentieth century. They are called âright' whales because they were the âright' ones to catch for oil and bones and profit. Though the population is recovering, you'd be lucky to spot one today.

The relative accessibility of the Peninsula and its surrounding islands coupled with the abundant whales and seals that the earliest explorers found in its water mean it has the longest record of exploitation on the continent. The human touch here is at its most evident, and also at its most unedifying.

In 1892 one American sealer, who had worked in Antarctica then for more than twenty years, told the US Congress:

Â

We killed everything, old and young, that we could get in gunshot of, excepting the black pups, whose skins were unmarketable, and most all of these died of starvation, having no means of sustenance . . . The seals in all these localities have been destroyed entirely by this indiscriminate killing of old and young, male and female. If the seals in these regions had been protected and only a certain number ofâdogs' (young male seals unable to hold their positions on the beaches) allowed to be killed, these islands and coasts would be again populous with seal life. The seals would certainly not have decreased and would have produced an annual supply of skins for all times. As it is, however, seals in the Antarctic regions are practically extinct, and I have given up the business as unprofitable.

4

Â

The whaling and sealing industries were akin to mining: go there, grab what you can and leave. The Antarctic Treaty now bans any commercial exploitation, but both whaling and sealing industries collapsed through their own short-sighted overuse of resources long before the international treaties kicked in.