Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (11 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

T

he first two chapters introduce and illustrate antifragility.

Chapter 3

introduces a distinction between the organic and the mechanical, say, between your cat and a washing machine.

Chapter 4

is about how the antifragility of some comes from the fragility of others, how errors benefit some, not others—the sort of things people tend to call evolution and write a lot, a lot about.

Please cut my head off—How by some magic, colors become colors—How to lift weight in Dubai

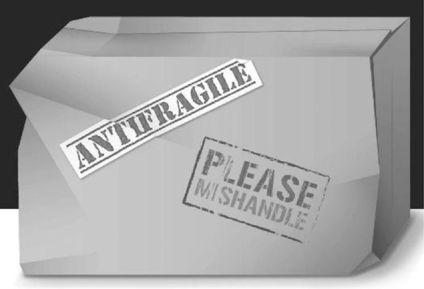

You are in the post office about to send a gift, a package full of champagne glasses, to a cousin in Central Siberia. As the package can be damaged during transportation, you would stamp “fragile,” “breakable,” or “handle with care” on it (in red). Now what is the exact opposite of such situation, the exact opposite of “fragile”?

Almost all people answer that the opposite of “fragile” is “robust,” “resilient,” “solid,” or something of the sort. But the resilient, robust (and company) are items that neither break nor improve, so you would not need to write anything on them—have you ever seen a package with “robust” in thick green letters stamped on it? Logically, the exact opposite of a “fragile” parcel would be a package on which one has written “please mishandle” or “please handle carelessly.” Its contents would not just be unbreakable, but would benefit from shocks and a wide array of trauma. The fragile is the package that would be

at best

unharmed, the robust would be

at best

and

at worst

unharmed. And the opposite of fragile is therefore what is

at worst

unharmed.

We gave the appellation “antifragile” to such a package; a neologism was necessary as there is no simple, noncompound word in the

Oxford

English Dictionary

that expresses the point of reverse fragility. For the idea of antifragility is not part of our consciousness—but, luckily, it is part of our ancestral behavior, our biological apparatus, and a ubiquitous property of every system that has survived.

FIGURE 1

. A package begging for stressors and disorder. Credit: Giotto Enterprise and George Nasr.

To see how alien the concept is to our minds, repeat the experiment and ask around at the next gathering, picnic, or pre-riot congregation what’s the antonym of fragile (and specify insistently that you mean the

exact reverse,

something that has opposite properties and payoff). The likely answers will be, aside from robust: unbreakable, solid, well-built, resilient, strong, something-proof (say, waterproof, windproof, rustproof)—unless they’ve heard of this book. Wrong—and it is not just individuals but branches of knowledge that are confused by it; this is a mistake made in every dictionary of synonyms and antonyms I’ve found.

Another way to view it: since the opposite of

positive

is

negative,

not

neutral,

the opposite of positive fragility should be negative fragility (hence my appellation “antifragility”), not neutral, which would just convey robustness, strength, and unbreakability. Indeed, when one writes things down mathematically, antifragility is fragility with a negative sign in front of it.

1

This blind spot seems universal. There is no word for “antifragility”

in the main known languages, modern, ancient, colloquial, or slang. Even Russian (Soviet version) and Standard Brooklyn English don’t seem to have a designation for antifragility, conflating it with robustness.

2

Half of life—the interesting half of life—we don’t have a name for.

If we have no common name for antifragility, we can find a mythological equivalence, the expression of historical intelligence through potent metaphors. In a Roman recycled version of a Greek myth, the Sicilian tyrant Dionysius II has the fawning courtier Damocles enjoy the luxury of a fancy banquet, but with a sword hanging over his head, tied to the ceiling with a single hair from a horse’s tail. A horse’s hair is the kind of thing that eventually breaks under pressure, followed by a scene of blood, high-pitched screams, and the equivalent of ancient ambulances. Damocles is fragile—it is only a matter of time before the sword strikes him down.

In another ancient legend, this time the Greek recycling of an ancient Semitic and Egyptian legend, we find Phoenix, the bird with splendid colors. Whenever it is destroyed, it is reborn from it own ashes. It always returns to its initial state. Phoenix happens to be the ancient symbol of Beirut, the city where I grew up. According to legend, Berytus (Beirut’s historical name) has been destroyed seven times in its close to five-thousand-year history, and has come back seven times. The story seems cogent, as I myself saw the eighth episode; central Beirut (the ancient part of the city) was completely destroyed for the eighth time during my late childhood, thanks to the brutal civil war. I also saw its eighth rebuilding.

But Beirut was, in its latest version, rebuilt in even better shape than the previous incarnation—and with an interesting irony: the earthquake of

A.D.

551 had buried the Roman law school, which was discovered, like a bonus from history, during the reconstruction (with archeologists

and real estate developers trading public insults). That’s not Phoenix, but something else beyond the robust. Which brings us to the third mythological metaphor: Hydra.

Hydra, in Greek mythology, is a serpent-like creature that dwells in the lake of Lerna, near Argos, and has numerous heads. Each time one is cut off, two grow back. So harm is what it likes. Hydra represents antifragility.