Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (22 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Note another element of Switzerland: it is perhaps the most successful country in history, yet it has traditionally had a very low level of university education compared to the rest of the rich nations. Its system, even in banking during my days, was based on apprenticeship models, nearly vocational rather than the theoretical ones. In other words, on

techne

(crafts and know how), not

episteme

(book knowledge, know what).

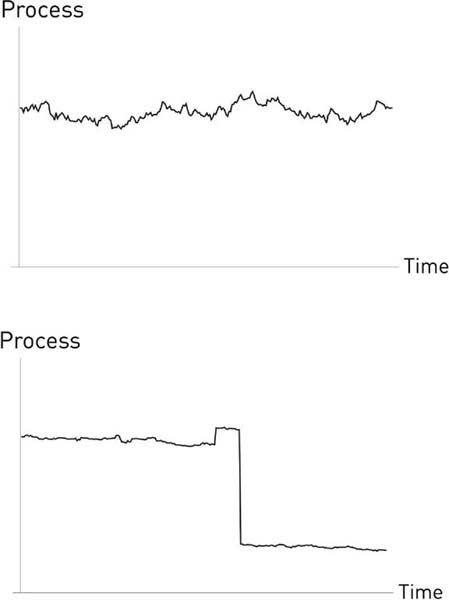

Let us now examine the technical aspects of the process, a more statistical view of the effect of human intervention on the volatility of affairs. There is a certain mathematical property to this bottom-up volatility, and to the volatility of natural systems. It generates the kind of randomness I call Mediocristan—plenty of variations that might be scary, but tend to cancel out in the aggregate (over time, or over the collection of municipalities that constitute the larger confederation or entity)—rather than the unruly one called Extremistan, in which you have mostly stability and occasionally

large chaos—errors there have large consequences. One fluctuates, the other jumps. One has a lot of small variations, the other varies in lumps. Just like the income of the driver compared to that of bank employee. The two types of randomness are qualitatively distinct.

Mediocristan has a lot of variations, not a single one of which is extreme; Extremistan has few variations, but those that take place are extreme.

Another way to understand the difference: your caloric intake is from Mediocristan. If you add the calories you consume in a year, even without adjusting for your lies, not a single day will represent much of the total (say, more than 0.5 percent of the total, five thousand calories when you may consume eight hundred thousand in a year). So the exception, the rare event, plays an inconsequential role in the aggregate and the long-term. You cannot double your weight in a single day, not even a month, not possibly in a year—but you can double your net worth or lose half of it in a single moment.

By comparison, if you take the sale of novels, more than half of sales (and perhaps 90 percent of profits) tends to come from the top 0.1 percent, so the exception, the one-in-a-thousand event, is dominant there. So financial matters—and other economic matters—tend to be from Extremistan, just like history, which moves by discontinuities and jumps from one state to another.

4

FIGURE 3

. Municipal noise, distributed variations in the souks (first) compared to that of centralized or human-managed systems (second)—or, equivalently, the income of a taxi driver (first) and that of an employee (second). The second graph shows moves taking place from cascade to cascade, or Black Swan to Black Swan. Human overintervention to smooth or control processes causes a switch from one kind of system, Mediocristan, into another, Extremistan. This effect applies to all manner of systems with constrained volatility—health, politics, economics, even someone’s mood with and without Prozac. Or the difference between the entrepreneur-driven Silicon Valley (first) and the banking system (second).

Figure 3

illustrates how antifragile systems are hurt when they are deprived of their natural variations (mostly thanks to naive intervention). Beyond municipal noise, the same logic applies to: the child who, after spending time in a sterilized environment, is left out in the open; a system with dictated political stability from the top; the effects of price controls; the advantages of size for a corporation; etc. We switch from a system that produces steady but controllable volatility (Mediocristan), closer to the statistical “bell curve” (from the benign family of the Gaussian or Normal Distribution), into one that is highly unpredictable and moves mostly by jumps, called “fat tails.” Fat tails—a synonym for Extremistan—mean that remote events, those in what is called the “tails,” play a disproportionate role. One (first graph) is volatile; it fluctuates but does not sink. The other (second graph) sinks without significant fluctuations outside of episodes of turmoil. In the long run the second system will be far more volatile—but volatility comes in lumps. When we constrain the first system we tend to get the second outcome.

Note also that in Extremistan predictability is very low. In the second, pseudo-smooth kind of randomness, mistakes appear to be rare, but they will be large, often devastating when they occur. Actually, an argument we develop in

Book IV

, anything locked into planning tends to fail precisely because of these attributes—it is quite a myth that planning helps corporations: in fact we saw that the world is too random and unpredictable to base a policy on visibility of the future. What survives comes from the interplay of some fitness and environmental conditions.

Let me now move back from the technical jargon and graphs of Fat Tails and Extremistan to colloquial Lebanese. In Extremistan, one is prone to be fooled by the properties of the past and get the story exactly backwards. It is easy, looking at what is happening in the second graph of

Figure 3

, before the big jump down, to believe that the system is now safe, particularly when the system has made a progressive switch from the “scary” type of visibly volatile randomness at left to the apparently safe right. It looks like a drop in volatility—and it is not.

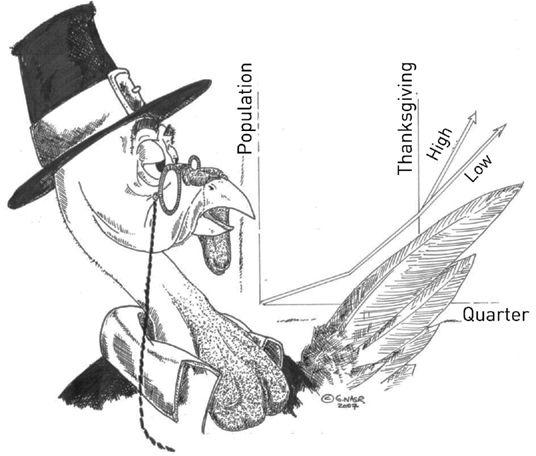

FIGURE 4

. A turkey using “evidence”; unaware of Thanksgiving, it is making “rigorous” future projections based on the past. Credit: George Nasr

A turkey is fed for a thousand days by a butcher; every day confirms to its staff of analysts that butchers love turkeys “with increased statistical confidence.” The butcher will keep feeding the turkey until a few days before Thanksgiving. Then comes that day when it is really not a very good idea to be a turkey. So with the butcher surprising it, the turkey will have a revision of belief—right when its confidence in the statement that

the butcher loves turkeys

is maximal and “it is very quiet” and soothingly predictable in the life of the turkey. This example builds on an adaptation of a metaphor by Bertrand Russell. The key here is that such a surprise will be a Black Swan event; but just for the turkey, not for the butcher.

We can also see from the turkey story the mother of all harmful mistakes: mistaking absence of evidence (of harm) for evidence of absence, a mistake that we will see tends to prevail in intellectual circles and one that is grounded in the social sciences.

So our mission in life becomes simply “how not to be a turkey,” or, if possible, how to be a turkey in reverse—antifragile, that is. “Not being a turkey” starts with figuring out the difference between true and manufactured stability.

The reader can easily imagine what happens when constrained,

volatility-choked systems explode. We have a fitting example: the removal of the Baath Party, with the abrupt toppling of Saddam Hussein and his regime in 2003 by the United States. More than a hundred thousand persons died, and ten years later, the place is still a mess.

We started the discussion of the state with the example of Switzerland. Now let us go a little bit farther east.

The northern Levant, roughly today’s northern part of Syria and Lebanon, stayed perhaps the most prosperous province in the history of mankind, over the long, very long stretch of time from the pre-pottery Neolithic until very modern history, the middle of the twentieth century. That’s twelve thousand years—compared to, say, England, which has been prosperous for about five hundred years, or Scandinavia, now only prosperous for less than three hundred years. Few areas on the planet have managed to thrive with so much continuity over any protracted stretch of time, what historians call

longue durée

. Other cities came and went; Aleppo, Emesa (today Homs), and Laodicea (Lattakia) stayed relatively affluent.

The northern Levant was since ancient times dominated by traders, largely owing to its position as a central spot on the Silk Road, and by agricultural lords, as the province supplied wheat to much of the Mediterranean world, particularly Rome. The area supplied a few Roman emperors, a few Catholic popes before the schisms, and more than thirty Greek language writers and philosophers (which includes many of the heads of Plato’s academy), in addition to the ancestors of the American visionary and computer entrepreneur Steve Jobs, who brought us the Apple computer, on one of which I am recopying these lines (and the iPad tablet, on which you may be reading them). We know of the autonomy of the province from the records during Roman days, as it was then managed by the local elites, a decentralized method of ruling through locals that the Ottoman retained. Cities minted their own coins.

Then two events took place. First, after the Great War, one part of the northern Levant was integrated into the newly created nation of Syria, separated from its other section, now part of Lebanon. The entire area had been until then part of the Ottoman Empire, but functioned as somewhat autonomous regions—Ottomans, like the Romans before them, let local elites run the place so long as sufficient tax was paid,

while they focused on their business of war. The Ottoman type of imperial peace, the

pax Ottomana

, like its predecessor the

pax Romana,

was good for commerce. Contracts were enforced, and that is what governments are needed for the most. In the recent nostalgic book

Levant,

Philip Mansel documents how the cities of the Eastern Mediterranean operated as city-states separated from the hinterland.

Then, a few decades into the life of Syria, the modernist Baath Party came to further enforce utopias. As soon as the Baathists centralized the place and enforced their statist laws, Aleppo and Emesa went into instant decline.

What the Baath Party did, in its “modernization” program, was to remove the archaic mess of the souks and replace them with the crisp modernism of the office building.

The effect was immediately visible: overnight the trading families moved to places such as New York and New Jersey (for the Jews), California (for the Armenians), and Beirut (for the Christians). Beirut offered a commerce-friendly atmosphere, and Lebanon was a benign, smaller, disorganized state without any real central government. Lebanon was small enough to be a municipality on its own: it was smaller than a medium-size metropolitan area.

But while Lebanon had all the right qualities, the state was

too

loose, and by allowing the various Palestinian factions and the Christian militias to own weapons, it caused an arms race between the communities while placidly watching the entire buildup. There was also an imbalance between communities, with the Christians trying to impose their identity on the place. Disorganized is invigorating; but the Lebanese state was one step too disorganized. It would be like allowing each of the New York mafia bosses to have a larger army than the Joint Chiefs of Staff (just imagine John Gotti with missiles). So in 1975 a raging civil war started in Lebanon.

A sentence that still shocks me when I think about it was voiced by one of my grandfather’s friends, a wealthy Aleppine merchant who fled the Baath regime. When my grandfather asked his friend during the Lebanese war why he did not go back to Aleppo, his answer was categorical: “We people of Aleppo prefer war to prison.” I thought that he meant that they were going to put him in jail, but then I realized that by “prison” he meant the loss of political and economic freedoms.

Economic life, too, seems to prefer war to prison. Lebanon and Northern Syria had very similar wealth per individual (what economists call Gross Domestic Product) about a century ago—and had identical cultures, language, ethnicities, food, and even jokes. Everything was the same except for the rule of the “modernizing” Baath Party in Syria compared to the totally benign state in Lebanon. In spite of a civil war that decimated the population, causing an acute brain drain and setting wealth back by several decades, in addition to every possible form of chaos that rocked the place, today Lebanon has a considerably higher standard of living—between three and six times the wealth of Syria.