Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (43 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

All this does not mean that tinkering and trial and error are devoid of narrative: they are just not overly dependent on the narrative being true—the narrative is not epistemological but instrumental. For instance, religious stories might have no value as narratives, but they may get you to do something convex and antifragile you otherwise would not do, like mitigate risks. English parents controlled children with the false narrative that if they didn’t behave or eat their dinner, Boney (Napoleon Bonaparte) or some wild animal might come and take them away. Religions often use the equivalent method to help adults get out of trouble, or avoid debt. But intellectuals tend to believe their own b***t and take their ideas too literally, and that is vastly dangerous.

Consider the role of heuristic (rule-of-thumb) knowledge embedded in traditions. Simply, just as evolution operates on individuals, so does it act on these tacit, unexplainable rules of thumb transmitted through generations—what Karl Popper has called evolutionary epistemology. But let me change Popper’s idea ever so slightly (actually quite a bit): my take is that this evolution is not a competition between ideas, but between humans and systems based on such ideas. An idea does not survive because it is better than the competition, but rather because the person who holds it has survived! Accordingly, wisdom you learn from your grandmother should be vastly superior (empirically, hence scientifically) to what you get from a class in business school (and, of course, considerably cheaper). My sadness is that we have been moving farther and farther away from grandmothers.

Expert problems (in which the expert knows a lot but less than he thinks he does) often bring fragilities, and acceptance of ignorance the reverse.

3

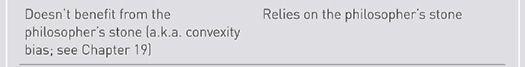

Expert problems put you on the wrong side of asymmetry. Let us examine the point with respect to risk. When you are fragile you need to know a lot more than when you are antifragile. Conversely, when you think you know more than you do, you are fragile (to error).

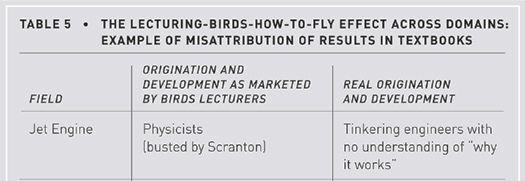

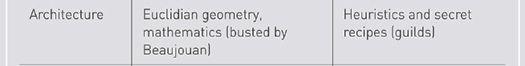

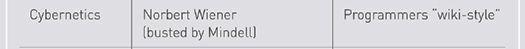

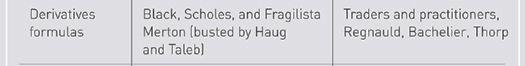

We showed earlier the evidence that classroom education does not

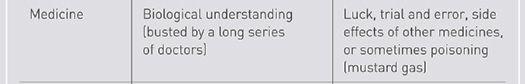

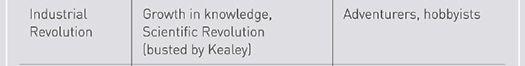

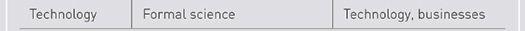

lead to wealth as much as it comes from wealth (an epiphenomenon). Next let us see how, similarly, antifragile risk taking—not education and formal, organized research—is largely responsible for innovation and growth, while the story is dressed up by textbook writers. It does not mean that theories and research play no role; it is that just as we are fooled by randomness, so we are fooled into overestimating the role of good-sounding ideas. We will look at the confabulations committed by historians of economic thought, medicine, technology, and other fields that tend to systematically downgrade practitioners and fall into the green lumber fallacy.

1

The halo effect is largely the opposite of domain dependence.

2

At first I thought that economic theories were not necessary to understand short-term movements in exchange rates, but it turned out that the same limitation applied to long-term movements as well. Many economists toying with foreign exchange have used the notion of “purchasing power parity” to try to predict exchange rates on the basis that in the long run “equilibrium” prices cannot diverge too much and currency rates need to adjust so a pound of ham will eventually need to carry a similar price in London and Newark, New Jersey. Put under scrutiny, there seems to be no operational validity to this theory—currencies that get expensive tend to get even more expensive, and most Fat Tonys in fact made fortunes following the inverse rule. But theoreticians would tell you that “in the long run” it should work. Which long run? It is impossible to make a decision based on such a theory, yet they still teach it to students, because being academics, lacking heuristics, and needing something complicated, they never found anything better to teach.

3

Overconfidence leads to reliance on forecasts, which causes borrowing, then to the fragility of leverage. Further, there is convincing evidence that a PhD in economics or finance causes people to build vastly more fragile portfolios. George Martin and I listed all the major financial economists who were involved with funds, calculated the blowups by funds, and observed a far higher proportional incidence of such blowups on the part of finance professors—the most famous one being Long Term Capital Management, which employed Fragilistas Robert Merton, Myron Scholes, Chi-Fu Huang, and others.

The birds may perhaps listen—Combining stupidity with wisdom rather than the opposite—Where we look for the arrow of discovery—A vindication of trial and error

Because of a spate of biases, historians are prone to epiphenomena and other illusions of cause and effect. To understand the history of technology, you need accounts by nonhistorians, or historians with the right frame of mind who developed their ideas by watching the formation of technologies, instead of just reading accounts concerning it. I mentioned earlier Terence Kealey’s debunking of the so-called linear model and that he was a practicing scientist.

1

A practicing laboratory scientist, or an engineer, can witness the real-life production of, say, pharmacological innovations or the jet engine and can thus avoid falling for epiphenomena, unless he was brainwashed prior to starting practice.

I have seen evidence—as an eyewitness—of results that owe

nothing

to academizing science, rather evolutionary tinkering that was dressed up and claimed to have come from academia.