Antony and Cleopatra (4 page)

Read Antony and Cleopatra Online

Authors: Colleen McCullough

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Historical Fiction, #Historical, #Romance, #Antonius; Marcus, #Egypt - History - 332-30 B.C, #Biographical, #Cleopatra, #Biographical Fiction, #Romans, #Egypt, #Rome - History - Civil War; 49-45 B.C, #Rome, #Romans - Egypt

“Sensible advice that I intend to take,” Antony said, “but it won’t be anything like enough. Finally I understand why Caesar was determined to conquer the Parthians—there’s no real wealth to be had this side of Mesopotamia. Oh,

curse

Octavianus! He pinched Caesar’s war chest, the little worm! While I was in Bithynia all the letters from Italia said he was dying in Brundisium, would never last ten miles on the Via Appia. And what do the stay-at-home letters have to say here in Tarsus? Why, that he coughed and spluttered all the way to Rome, where he’s busy smarming up to the legion representatives. Commandeering the public land of every place that cheered for Brutus and Cassius when he isn’t bending his arse over a barrel for apes like Agrippa to bugger!”

Get him off the subject of Octavian, thought Dellius, or he will forget sobriety and holler for unwatered wine. That snaky bitch Glaphyra doesn’t help—too busy working for her sons. So he clicked his tongue, a sound of sympathy, and eased Antony back onto the subject of where to get money in the bankrupt East.

“There is an alternative to the Parthians, Antonius.”

“Antioch? Tyre, Sidon? Cassius got to them first.”

“Yes, but he didn’t get as far as Egypt.” Dellius let the word “Egypt” drop from his lips like syrup. “Egypt can buy and sell Rome—everyone who ever heard Marcus Crassus talk knows

that

. Cassius was on his way to invade Egypt when Brutus summoned him to Sardis. He took Allienus’s four Egyptian legions, yes, but, alas, in Syria. Queen Cleopatra cannot be impeached for that, but she didn’t send any aid to you and Octavianus either. I think her inaction can be construed as worth a ten-thousand-talent fine.”

Antony grunted. “Huh! Daydreams, Dellius.”

“No, definitely not! Egypt is

fabulously

rich.”

Half listening, Antony studied a letter from his warlike wife, Fulvia. In it she complained about Octavian’s perfidies and described the precariousness of Octavian’s position in blunt, graphic terms. Now, she scrawled in her own hand, was the time to rouse Italia and Rome against him! And Lucius thought this too: Lucius was beginning to enlist legions. Rubbish, thought Antony, who knew his brother Lucius too well to deem him capable of deploying ten beads on an abacus.

Lucius

leading a revolution? No, he was just enlisting men for big brother Marcus. Admittedly, Lucius was consul this year, but his colleague was Vatia, who would be running things. Oh, women! Why couldn’t Fulvia devote herself to disciplining her children? The brood she had borne Clodius was grown and off her hands, but she still had her son by Curio and his own two sons.

Of course by now Antony knew that he would have to postpone his expedition against the Parthians for at least another year. Not only did shortage of funds render it impossible; so did the need to watch Octavian closely. His most competent marshals, Pollio, Calenus, and trusty old Ventidius, had to be stationed in the West with the bulk of his legions just to keep that eye on Octavian. Who had written him a letter begging that he use his influence to call off Sextus Pompeius, busy raiding the sea lanes to steal Rome’s wheat like a common pirate. To tolerate Sextus Pompeius had not been a part of their agreement, Octavian whinged—did Marcus Antonius not remember how the two of them had sat down together after Philippi to divide up the duties of the three triumvirs?

Indeed I remember, thought Antony grimly. It was after I won Philippi that I saw as through crystal that there was nowhere in the West to reap enough glory for me to eclipse Caesar. To surpass Caesar, I will have to crush the Parthians.

Fulvia’s scroll fell to the desk top, curled itself up. “Do you really believe that Egypt can produce that sort of money?” he asked, looking up at Dellius.

“Certainly!” said Dellius heartily. “Think about it, Antonius! Gold from Nubia, ocean pearls from Taprobane, precious stones from the Sinus Arabicus, ivory from the Horn of Africa, spices from India and Aethiopia, the world’s paper monopoly, and more wheat than there are people to eat it. The Egyptian public income is six thousand gold talents a year, and the sovereign’s private income another six thousand!”

“You’ve been doing your homework,” said Antony with a grin.

“More willingly than ever I did when a schoolboy.”

Antony got up and walked to the window that looked out over the agora to where, between the trees, ship’s masts speared the cloudless sky. Not that he saw any of it; his eyes were turned inward, remembering the scrawny little creature Caesar had installed in a marble villa on the wrong side of Father Tiber. How Cleopatra had railed at being excluded from the interior of Rome! Not in front of Caesar, who wouldn’t put up with tantrums, but behind his back it had been a different story. All Caesar’s friends had taken a turn trying to explain to her that she, an anointed queen, was religiously forbidden to enter Rome. Which hadn’t stopped her complaining! Thin as a stick she had been, and no reason to suppose she’d plumped out since she returned home after Caesar died. Oh, how Cicero had rejoiced when word got around that her ship had gone to the bottom of Our Sea! And how downcast he had been when the rumor proved false. The least of Cicero’s worries, as things turned out—he ought never to have thundered forth in the Senate against

me

! Tantamount to a death wish. After he was executed, Fulvia thrust a pen through his tongue before I exhibited his head on the rostra. Fulvia! Now there’s a woman! I never cared for Cleopatra, never bothered to go to her soirees or her famous dinner parties—too highbrow, too many scholars, poets, and historians. And all those beast-headed gods in the room where she prayed! I admit that I never understood Caesar, but his passion for Cleopatra was the biggest mystery of all.

“Very well, Quintus Dellius,” Antony said aloud. “I will order the Queen of Egypt to appear before me in Tarsus to answer charges that she aided Cassius. You can carry the summons yourself.”

How wonderful! thought Dellius, setting off the next day on the road that led first to Antioch and then south along the coast to Pelusium. He had demanded to be outfitted in state, and Antony had obliged by giving him a small army of attendants and two squadrons of cavalry as a bodyguard. No traveling by litter, alas! Too slow to suit the impatient Antony, who had given him one month to reach Alexandria, a thousand miles from Tarsus. Which meant Dellius had to hurry. After all, he didn’t know how long it was going to take to convince the Queen that she must obey Antony’s summons, appear before his tribunal in Tarsus.

Chin on her hand, Cleopatra watched Caesarion as he bent over his wax tablets, Sosigenes at his right hand, supervising. Not that her son needed him; Caesarion was seldom wrong, and never mistaken. The leaden weight of grief shifted in her chest, made her swallow painfully. To look at Caesar’s son was to look at Caesar, who at this age would have been Caesarion’s image: tall, graceful, golden-haired, long bumpy nose, full humorous lips with delicate creases in their corners. Oh, Caesar, Caesar! How have I lived without you? And they

burned

you, those barbaric Romans! When my time is come, there will be no Caesar beside me in my tomb, to rise with me and walk the Realm of the Dead. They put your ashes in a jar and built a round marble monstrosity to accommodate the jar. Your friend Gaius Matius chose the epitaph: VENI. VIDI. VICI etched in gold on polished black stone. But I have never seen your tomb, nor want to. All I have is a huge lump of grief that never goes away. Even when I manage to sleep, it is there to haunt my dreams. Even when I look at our son, it is there to mock my aspirations. Why do I never think of the happy times? Is that the pattern of loss, to dwell upon the emptiness of today? Since those self-righteous Romans murdered you, my world is ashes doomed never to mingle with yours. Think on it, Cleopatra, and weep.

The sorrows were many. First and worst, river Nilus failed to inundate. For three years in a row the life-giving water had not spread across the fields to wet them, soak in, and soften the seeds. The people starved. Then came the plague, slowly creeping up the length of river Nilus from the Cataracts to Memphis and the start of the Delta, then into the branches and canals of the Delta, and finally to Alexandria.

And always, she thought, I made the wrong decisions, Queen Midas on a throne of gold, who didn’t understand until it was too late that people cannot eat gold. Not for any amount of gold could I persuade the Syrians and the Arabs to venture down Nilus and collect the jars of grain waiting on every jetty. It sat there until it rotted, and then there were not enough people to irrigate by hand, and no crops germinated at all. I looked at the three million inhabitants of Alexandria and decided that only one million of them could eat, so I issued an edict that stripped the Jews and Metics of their citizenship. An edict that forbade them to buy wheat from the granaries, the right of citizens only. Oh, the riots! And it was all for nothing. The plague came to Alexandria and killed two million without regard for citizenship. Greeks and Macedonians died, people for whom I had abandoned the Jews and Metics. In the end, there was plenty of grain for those who did not die, Jews and Metics as well as Greeks and Macedonians. I gave them back the citizenship, but they hate me now. I made all the wrong decisions. Without Caesar to guide me, I proved myself a poor ruler.

In less than two months my son will be six years old, and I am childless, barren. No sister for him to marry, no brother to take his place should anything befall him. So many nights of love with Caesar in Rome, yet I did not quicken. Isis has cursed me.

Apollodorus hurried in, his golden chain of office clinking. “My lady, an urgent letter from Pythodorus of Tralles.”

Down went the hand, up went the chin. Cleopatra frowned. “Pythodorus? What does he want?”

“Not gold, at any rate,” said Caesarion, looking up from his tablets with a grin. “He’s the richest man in Asia Province.”

“Pay attention to your sums, boy!” said Sosigenes.

Cleopatra got up from her chair and walked across to an open section of wall where the light was good. A close examination of the green wax seal showed a small temple in its middle and the words PYTHO. TRALLES around its edge. Yes, it seemed authentic. She broke it and unfurled the scroll, written in a hand that said no scribe had been made privy to its contents. Too untidy.

Pharaoh and Queen, Daughter of Amun-Ra,

I write as one who loved the God Julius Caesar for many years, and as one who respected his devotion to you. Though I am aware you have informants to keep you apprised of what is going on in Rome and the Roman world, I doubt that any of them stands high in the confidence of Marcus Antonius. You will of course know that Antonius journeyed from Philippi to Nicomedia last November, and that many kings, princes, and ethnarchs met him there. He did virtually nothing to alter the state of affairs in the East, but he did command that twenty thousand silver talents be paid to him immediately. The size of this tribute shocked all of us.

After visiting Galatia and Cappadocia, he arrived in Tarsus. I followed him with the two thousand silver talents we ethnarchs of Asia Province had managed to scrape together. Where were the other eighteen thousand talents? he asked. I think I succeeded in convincing him that nothing like this sum is to be found, but his answer was one we have grown used to: pay him nine more years’ tribute in advance, and we would be forgiven. As if we have salted away ten years’ tribute against the day! They just do not listen, these Roman governors.

I crave your pardon, great queen, for burdening you with our troubles, and our troubles are not why I am writing this in secret. This is to warn you that within a very few days you will receive a visit from one Quintus Dellius, a grasping, cunning little man who has wormed his way into Marcus Antonius’s good opinion. His whisperings into Antonius’s ear are aimed at filling Antonius’s war chest, for Antonius hungers to do what Caesar did not live to do—conquer the Parthians. Cilicia Pedia is being scoured from end to end, the brigands chased from their strongholds and the Arab raiders back across the Amanus. A profitable exercise, but not profitable enough, so Dellius suggested that Antonius summon you to Tarsus and there fine you ten thousand

gold

talents for supporting Gaius Cassius.There is nothing I can do to help you, dear good Queen, beyond warn you that Dellius is even now upon his way south. Perhaps with foreknowledge you will have the time to devise a scheme to thwart him and his master.

Cleopatra handed the scroll back to Apollodorus and stood chewing her lip, eyes closed. Quintus Dellius? Not a name she recognized, therefore no one with sufficient clout in Rome to have attended her receptions, even the largest; Cleopatra never forgot a name or the face attached to it. He would be a Vettius, some ignoble knight with smarm and charm, just the type to appeal to a boor like Marcus Antonius. Him, she remembered! Big and burly, thews like Hercules, shoulders as wide as mountains, an ugly face whose nose strove to meet an up-thrust chin across a small, thick-lipped mouth. Women swooned over him because he was supposed to have a gigantic penis—what a reason to swoon! Men liked him for his bluff, hearty manner, his confidence in himself. But Caesar, whose close cousin he was, had grown disenchanted with him—the main reason, she was sure, why Antonius’s visits to her had been few. When left in charge of Italia he had slaughtered eight hundred citizens in the Forum Romanum, a crime Caesar could not forgive. Then he tried to woo Caesar’s soldiers and ended in instigating a mutiny that had broken Caesar’s heart.

Of course her agents had reported that many thought Antony was a part of the plot to assassinate Caesar, though she herself was not sure; the occasional letter Antony had written to her explained that he had had no choice other than to ignore the murder, foreswear vengeance on the assassins, even condone their conduct. And in those letters Antony had assured her that as soon as Rome settled down, he would recommend Caesarion to the Senate as one of Caesar’s chief heirs. To a woman devastated by grief, his words had been balm. She

wanted

to believe them! Oh, no, he wasn’t saying that Caesarion should be admitted into Roman law as Caesar’s Roman heir! Only that Caesarion’s right to the throne of Egypt should be sanctioned by the Senate. Were it not, her son would be faced with the same problems that had dogged her father, never certain of his tenure on the throne because Rome said Egypt really belonged to Rome. Any more than she herself had been certain until Caesar entered her life. Now Caesar was gone, and his nephew Gaius Octavius had usurped more power than any lad of eighteen had ever done before. Calmly, cannily, quickly. At first she had thought of young Octavian as a possible father for more children, but he had rebuffed her in a brief letter she could still recite by heart.

Marcus Antonius, he of the reddish eyes and curly reddish hair, no more like Caesar than Hercules was like Apollo. Now he had turned his eyes toward Egypt—but not to woo Pharaoh. All he wanted was to fill his war chest with Egypt’s wealth. Well, that would never happen—never!

“Caesarion, it’s time you had some fresh air,” she said with brisk decision. “Sosigenes, I need you. Apollodorus, find Cha’em and bring him back with you. It’s council time.”

When Cleopatra spoke in that tone no one argued, least of all her son, who took himself off at once, whistling for his puppy, a small ratter named Fido.

“Read this,” she said curtly when the council assembled, thrusting the scroll at Cha’em. “All of you, read it.”

“If Antonius brings his legions, he can sack Alexandria and Memphis,” Sosigenes said, handing the scroll to Apollodorus. “Since the plague, no one has the spirit to resist. Nor do we have the numbers to resist. There are many gold statues to melt down.”

Cha’em was the high priest of Ptah, the creator god, and had been a beloved part of Cleopatra’s life since her tenth year. His brown, firm body was wrapped from just below the nipples to mid-calf in a flaring white linen dress, and around his neck he wore the complex array of chains, crosses, roundels, and breastplate proclaiming his position. “Antonius will melt nothing down,” he said firmly. “You will go to Tarsus, Cleopatra, meet him there.”

“Like a

chattel

? Like a

mouse

? Like a whipped

cur

?”

“No, like a mighty sovereign. Like Pharaoh Hatshepsut, so great her successor obliterated her cartouches. Armed with all the wiles and cunning of your ancestors. As Ptolemy Soter was the natural brother of Alexander the Great, you have the blood of many gods in your veins. Not only Isis, Hathor, and Mut, but Amun-Ra on two sides—from the line of the pharaohs and from Alexander the Great, who was Amun-Ra’s son and also a god.”

“I see where Cha’em is going,” said Sosigenes thoughtfully. “This Marcus Antonius is no Caesar, therefore he can be duped. You must awe him into pardoning you. After all, you didn’t aid Cassius, and he can’t prove you did. When this Quintus Dellius arrives, he will try to cow you. But you are Pharaoh, no minion has the power to cow you.”

“A pity that the fleet you sent Antonius and Octavianus was obliged to turn back,” said Apollodorus.

“Oh, what’s done is done!” Cleopatra said impatiently. She sat back in her chair, suddenly pensive. “No one can cow Pharaoh, but…Cha’em, ask Tach’a to look at the lotus petals in her bowl. Antonius might have a use.”

Sosigenes looked startled. “Majesty!”

“Oh, come, Sosigenes, Egypt matters more than any living being! I have been a poor ruler, deprived of Osiris time and time again! Do I care what kind of man this Marcus Antonius is? No, I do not! Antonius has Julian blood. If the bowl of Isis says there is enough Julian blood in him, then perhaps I can take more from him than he can from me.”

“I will do it,” said Cha’em, getting to his feet.

“Apollodorus, will Philopator’s river barge sustain a sea voyage to Tarsus at this time of year?”

The lord high chamberlain frowned. “I’m not sure, Majesty.”

“Then bring it out of its shed and send it to sea.”

“Daughter of Amun-Ra, you have many ships!”

“But Philopator built only two ships, and the oceangoing one rotted a hundred years ago. If I am to awe Antonius, I must arrive in Tarsus in a kind of state that no Roman has ever witnessed, not even Caesar.”

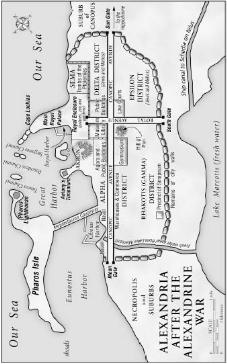

To Quintus Dellius, Alexandria was the most wondrous city in the world. The days when Caesar had almost destroyed it were seven years in the past, and Cleopatra had raised it in greater glory than ever. All the mansions down Royal Avenue had been restored, the Hill of Pan towered over the flat city lushly green, the hallowed precinct of Serapis had been rebuilt in the Corinthian mode, and where once siege towers had groaned and lumbered up and down Canopic Avenue, stunning temples and public institutions gave the lie to plague and famine. Indeed, thought Dellius erroneously, gazing at Alexandria from the top of Pan’s hill, for once in his life great Caesar exaggerated the degree of destruction he had wrought.

As yet he hadn’t seen the Queen, who was, a lordly man named Apollodorus had informed him loftily, on a visit to the Delta to see her paper manufactories. So he had been shown his quarters—very sumptuous they were, too—and left largely to his own devices. To Dellius, that didn’t mean simple sightseeing; with him he took a scribe who jotted down notes using a broad stylus on wax tablets.

At the Sema Dellius chuckled with glee. “Write, Lasthenes! ‘The tomb of Alexander the Great plus thirty-odd Ptolemies in a precinct dry-paved with collector’s-quality marble in blue with dark green swirls…. Twenty-eight gold statues, man-sized…. An Apollo by Praxiteles, painted marble…. Four painted marble works by some unidentified master, man-sized…. A painting by Zeuxis of Alexander the Great at Issus…. A painting of Ptolemy Soter by Nicias…. ’ Cease writing. The rest are not so fine.”