April Queen (22 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

In the Tour Maubergeonne of the ducal palace at Poitiers she could draw breath and plan her next move. She was fairly certain that the arrangement secretly arrived at with the late count of Anjou would be honoured by his son for his own selfish reasons, but Henry Plantagenet was a man who made promises and broke them all his life, so one could never be sure where one stood with him â as she was to find out.

On 6 April he called a meeting of his vassals in Normandy. In acquainting them with his intention of marrying the ex-queen of France without the king's permission in accordance with feudal custom, he was warning them to be ready for incursions from Frankish territory. As one of his assembled bishops must have pointed out to him, there was a significant impediment to his plan to marry Eleanor in that she was even more closely related to him than she had been to Louis. Leaving that detail to his clerics, Henry prepared to make his move.

In Aquitaine, Eleanor was busy with administrative chores, repudiating all the charters she had signed jointly with Louis on the grounds that they had been granted under constraint. It was with great relief that she welcomed the arrival in Poitiers during the second week of May of the nineteen-year-old duke of Normandy. Married life with him was certain to be more exciting than with Louis. So much so that even the sober Alfred Richard, nineteenth-century archivist of the

département

of Vienne, who devoted several hundred pages to Eleanor

in his comprehensive study of the counts of Poitou, stated that she was bored with Louis' platonic love and deliberately sought a brutal new lover in Henry because she was âone of those women who like to be knocked around'.

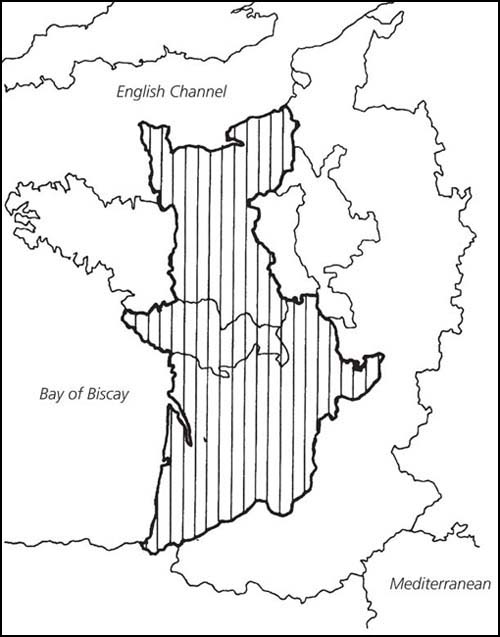

22

Like all the other slanders, the accusation is baseless. The facts are that though she had been denied a proper hearing in Louis' councils for the past few years, all Eleanor's life had been spent in the corridors of power. This was no love match. In marrying Henry, she was wedding the thirteen counties of Aquitaine and the county of Poitou to the duchy of Normandy, plus Anjou, Maine and Touraine. This master stroke created a power bloc that stretched all the way from the snows of the Pyrenees to the waters of the English Channel and eventually united nearly half of Louis' kingdom. On 18 May a ceremony in due form in Poitiers Cathedral

23

made her wife to the man who not only solved her pressing need for a spouse strong enough to protect her domains from present enemies, but owed her a lifelong debt of gratitude for making him the most powerful man in France. Ironically, he would become in the course of time her most implacable enemy of all.

A Son at Last

T

he immediate consequence of the May wedding was a war. Although of brief duration, it was the first round in a protracted series of hostilities caused by Eleanor’s divorce and remarriage that would last for three centuries and cost uncounted lives.

The first move was taken in Paris, when Louis was advised that Henry should be summoned to court on a charge of treason for failing to ask permission to marry from the suzerain to whom he had so lately sworn fealty. Technically, Eleanor was equally guilty, but no such accusation was levelled against her; nor was Louis ever overtly hostile to her in the future.

Curiously, neither Abbé Bernard nor Pope Eugenius could be persuaded to support the charge of treason. The Church was playing another game behind the scenes: in obedience to Eugenius’ instructions, Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury had refused to crown Stephen of Blois’ son Eustace of Boulogne as his successor to the crown of England.

No one at the Capetian court expected Henry of Anjou to put in an appearance; the summons was a way of clearing the ground for the

next step. Just over a month later that step was taken in concert with Stephen of Blois, who saw it as a way of weakening his son’s chief competitor for the throne of the island realm after his death. Attack being the best defence, he concerted with Louis a pre-emptive invasion of Henry’s territory, in which his contingent was to be led by Eustace. Robert of Dreux, forgiven for the attempted

coup d’état

while the king was in Outremer, joined the coalition, as did Thibault of Blois and Geoffrey Plantagenet, Henry’s younger brother, both of whom had failed to kidnap Eleanor on the flight from Paris. Having lost the mother, Thibault had gained the daughter, having just been betrothed to Eleanor’s second daughter, two-year-old Aelith. Henry of Champagne, another of Louis’ party, had just married Eleanor’s elder daughter Marie, which gave him a tentative claim to the duchy of Aquitaine that he would lose if she gave birth to a son by Henry of Anjou.

Deprived of his most trusted advisers by the recent deaths of Raoul de Vermandois and Thibault of Champagne, Louis belatedly realised that he was commander-in-chief in name only. Each member of the coalition was intent on carving up Henry’s and Eleanor’s domains from the Channel to the Pyrenees and grabbing the largest possible slice for himself.

1

Henry of Anjou had been anticipating this move ever since his council of war on 6 April. As events would prove repeatedly, he was adept at making his enemies think he was doing one thing when in fact he was doing another. In this case, when the coalition invaded just after Midsummer Day, they thought him preoccupied with his preparations to invade England from Barfleur, the little port in the lee of the Cotentin peninsula.

That was just a feint. If his true qualities had in the past been hidden by those of his father, now for the first time he showed his true mettle, riding horses into the ground and laying waste Robert of Dreux’s lands. Courage is better than numbers in war, said Vegetius, and speed better than courage. The speed and fury of Henry’s counter-attack appalled Louis, who fell ill with some kind of fever and retreated as soon as the Church called for a truce.

His blood up, Henry rode back to Anjou, which his brother had attempted to rise against him, and broke the rebellion there by capturing the castle at Montsoreau, garrisoned by Geoffrey’s supporters. Far from weakening Henry’s position, the abortive invasion had actually done him a double favour in forcing him to show his strength as a warning to his neighbours not to try to profit from his absence

when he did eventually invade England, and also obliging him to delay that invasion until the following year, when he was better prepared.

Eleanor’s and Henry’s combined possessions on 19 May 1152.

After seeing off the coalition, Henry spent the autumn with Eleanor. Their feudal progress through Aquitaine was hardly a honeymoon. After enjoying the grape harvest on her estates in Poitou – although

‘enjoying’ is perhaps the wrong word, for Henry never relaxed – they continued southward with the new duke of Aquitaine assessing the castles and fortified towns of Gascony both militarily and fiscally, and assuring himself that the new administrators who had replaced Louis’ men knew exactly who was now in charge.

He had already developed the style of travel that would anguish all but the hardiest of his courtiers on both sides of the Channel. That first journey Eleanor shared with him in the summer and autumn of 1152 fits the description by her sometime secretary Peter of Blois of his travels with Henry’s court a few years later:

If the King has announced that he will depart early next morning, the decision is sure to be changed … and he will sleep to midday. You will see pack animals waiting under their loads, teams of horses standing, heralds sleeping, court traders fretting, and everyone … grumbling. One runs to the whores … to ask them where the King is going, for this breed of courtier often knows the palace secrets.

2

That was a euphemism for saying how Henry spent his nights.

Peter also commented on those members of the court who had undergone bloodletting or taken laxatives but followed Henry’s precipitate departures, forfeiting their dignity and sometimes their lives, ‘risking to lose themselves rather than lose what they haven’t got and are not going to get’. Court life, he said, was death for the soul.

3

His fellow courtier Walter Map conveyed this hectic lifestyle in his

Courtiers’ Gossip

,

4

quoting St Augustine’s observation that he was in time and spoke of time, yet knew not what time was. ‘With a similar sense of amazement,’ wrote Map, ‘I could say that I am in the court and I speak of the court, but God knows what the court is. [It] is a pleasant place only for those who obtain its favour [which] comes regardless of reason, establishes itself regardless of merit, arrives obscurely from unknown causes.’

5

According to him, the entire retinue wore out their clothes, their mounts, their bodies and their souls, such was the relentless pace Henry expected of everyone in his service. Yet no courtier could risk not being present when summoned at any hour of the day or night, for those Henry had raised to greatness, he could cast down. And when they fell, they pulled others with them. ‘Friendship among those who are summoned to give the King counsel and undertake his business is one of the rarest things. Anxious ambition dominates their minds; each of them fears to be outstripped by the endeavours of the others. So is born envy, which

necessarily turns immediately into hatred.’

6

Thus Arnulf of Lisieux, a Norman vassal of Henry’s, wrote from his own bitter experience.

Yet Henry could be affable when hearing out petitioners. He could be generous to a captain who had lost his ship or a vassal who had lost a limb in the royal service or a peasant whose property had been damaged by the royal hunt or to the poor during time of famine. When relaxed, he joked with his intimates or called for needle and thread to mend his own clothes. He was tolerant of Jews and heretics, but not homosexuals, once authorising torture for some Templars accused of sodomy. Much of his legislation is a model of justice, while his forest laws were vindictively cruel.

Indifferent to food, he contented himself when necessary while travelling with gruel or bread and expected his companions to do the same. If he thought that this lifestyle might drive Eleanor to retire from the erratic progress and wait for him in the comital palace at Poitiers, he was wrong. The woman who had ridden across Turkey on the Second Crusade was tougher than that. Rising to every challenge, she was determined to establish her own position in the marriage from the outset, while quickly realising she would never have a fraction of the influence over her new husband that she had enjoyed over Louis.

Hyperactive, Henry rarely sat down except for a game of chess or to eat, and would be on the move again as soon as hunger was sated or the game over. Even during Mass he fidgeted continually, giving orders to his clerks or taking aside someone with whom he wished to talk. He dressed in costly but carelessly worn clothes, taking no interest in his appearance. His reddish hair was kept cut unfashionably short for the good reason that long hair became tangled by rubbing against the leather liner of a helmet of a man forever ready for combat. His nickname, Henry Curtmantle, referred to his habit of wearing a very short coat that gave little protection from the weather but made it quicker to mount and dismount.