April Queen (32 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

There was no way Henry could foresee that Adrian’s successor Alexander III would turn out to be the longest-serving pontiff of the twelfth century. For the most part appointed elderly, patriarchs tended not to be long in office. Within the century, six lasted a year or less. By making a man as accomplished as Becket Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162, Henry could reasonably have expected him to be elected pope in a few years’ time, given the backing of one of the two most powerful monarchs in Europe.

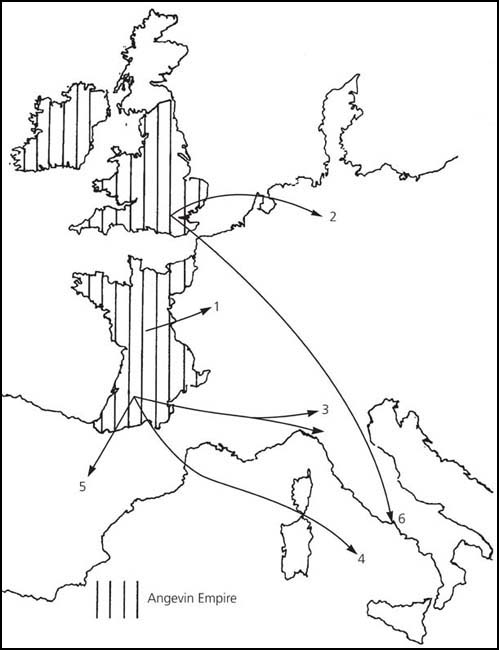

After this, with Becket’s military experience directing the considerable forces of the papal territories with their castles and wealth, Henry would have had in the spiritual leader of Europe a temporal ally, enabling him to secure that part of the long peninsula of Italy subject to the German Emperor and link up with the Norman presence in Sicily, Puglia and Calabria. And having done that, what more logical than to drive the frontiers of the empire back from the Rhône to the Rhine?

Was this Henry’s grand design? 1. Young Henry and Marguerite. 2. Princess Matilda and Henry of Saxony. 3. Re-attachment of Toulouse/Prince John and Alix de Maurienne/the Crown of Lombardy. 4. Princess Joanna and William II of Sicily. 5. Princess Eleanor and Alfonso of Castile. 6. The winning move: Becket to Pope.

And why stop there? There were vast territories inide Germany controlled by bishops who did not support Frederik Barbarossa. With the pope on his side, Henry could have been the master of all Europe. From a less advantageous beginning, Charlemagne had done it. While such a plan to dominate the whole of Europe cannot be proven, it explains a great deal that is otherwise inexplicable.

Henry had spent the formative years of his childhood in an intense relationship with the powerful, intelligent and scheming Empress Matilda in the west of England during the civil war. He had been raised to reclaim at all costs what she regarded as her birthright north of the Channel, in addition to inheriting the duchy of Normandy she had kept for him and his father’s cluster of territory in Anjou, Maine and Touraine.

Given her behaviour in the on-again, off-again marriage to Geoffrey the Fair, Matilda must have had a powerful reason to bear the three sons she gave him. Was it to ensure that one of them would eventually rule the empire and give her back her place in history as the mother of an emperor – there was no greater destiny for a noblewoman – out of which she had been cheated by her first husband’s early death? Germany, where she had as consort shared power with the Emperor Henry V and Italy, where she had commanded Henry V’s armies in her early twenties. It was there that she had wielded her greatest power, and it was there that Henry’s manoeuvrings are otherwise hard to fathom.

The only way Charlemagne had worked out of ruling the vast empire he had conquered had been by using his sons as viceroys. William the Conqueror had had the same idea. A paranoid ruler like Henry might well have thought that, if he could rely on no one else, at least the sons of his own blood could be counted on, each to rule a share in the greatest empire the world had known since the Roman Empire split into two parts in the late fifth century.

If Matilda did implant such a grand design in Henry’s youthful head – and plans like this are unlikely to be put in writing between two conspirators who trusted no one else – it would go a long way to explain all those sons and Eleanor’s bitterness at being discarded now. It would also explain why she was to support her sons against him after Becket’s obstinacy had aborted the grand design, and made it unlikely ever to be primed again.

The Christmas court in Argentan was a frigid affair. Just over a month later, on 1 February 1168, Princess Matilda was married in faraway Brunswick to Henry the Lion of Saxony. Before Eleanor could

continue her journey south, encumbered by the seven shiploads of belongings and furniture, her vassals of the houses of Lusignan and Angoulême, knowing that Henry was overstretched, renounced their allegiance to him and appealed to Louis to accept their fealty directly. While he vacillated, among the Poitevin strongholds Henry stormed and razed to the ground in violation of both the Truce and the Peace of God was the castle twenty miles south-west of Poitiers belonging to Hugues le Brun, a prisoner of the Saracens in the Holy Land, where he had been on crusade since 1163.

Before Easter Henry departed for Normandy, leaving as Eleanor’s constable or guardian Count Patrick of Salisbury, who took his orders directly from the king. With Eleanor’s encouragement, Patrick made a quick pilgrimage to Compostela, after which he was escorting her near Poitiers on 6 or 7 April when they rode into an ambush sprung by the Lusignans in retribution for the loss of their fortress. After conducting his charge to safety in a nearby castle while his men kept the intruders at bay, Patrick returned to the scene of the fighting.

Possibly they had been out for a day’s hunting or hawking, for which he had left his armour behind in Poitiers. Alternatively, it would have been normal on a hot day to remove his mail cotte and leggings, to have them transported on one of the packhorses in what should have been safe territory – just as the four knights who arrived to kill Becket on 29 December 1170 first checked that he was in the palace by the cathedral before going outside to put on their armour, packed away for the journey.

Mounted on a palfrey and not his charger, Count Patrick was at a triple disadvantage, lacking the manoeuvrability of his destrier and the protection of the high-cantled and -pommelled war saddle as well as any body armour. Stabbed in the back by either Guy or Geoffrey de Lusignan, he fell to the ground mortally wounded. The last thing he saw was his nephew William also cut down in attempt-ing to save him.

Taken prisoner and denied treatment for his wounds by his captors, the young knight was ransomed by Eleanor, who rewarded his courage and loyalty with gifts of arms and armour, horses, money and clothes, setting the man who would become famous as William the Marshal on a long career of loyal service to Henry and her sons, during which his path would cross hers many times. She could have kept him in her household. Instead, she commended him to the king as a suitable master-at-arms to teach the skills of war to Young Henry and keep him out of trouble – which gave her, as his patroness, a useful pair of eyes and ears within the Young King’s household.

William epitomised Chaucer’s ‘parfit gentle knight’ before the concept of chivalry was generally accepted. Tall, brown-haired and with an open and frank demeanour, he was a grandson of Gilbert, Marshal to Henry I. His father had at various times been Marshal to Henry I and Stephen of Blois. At the age of five or six William had been given as a hostage during the siege of Newbury Castle, and narrowly escaped being hanged when his father cheated on a truce to bring in reinforcements.

King Stephen was not a vindictive man. He offered to hand back the young hostage if his father would surrender the fortress. John Marshal refused, adding that his son’s fate was of no great moment, since he still had ‘the hammer and the anvil to forge better ones’. By way of reply to this insolence, some of the besiegers advised catapulting the boy alive into the fortress from a siege engine, but Stephen placed him under his personal protection. How often gallantry begat gallantry is a moot point, but this was an auspicious start to the career of the noblest warrior of the twelfth century, which would peak when he was appointed regent for Eleanor’s grandson Henry III in 1216.

Exactly how the Lusignans knew where Eleanor would be that day in April 1168 is an interesting question. Plainly Patrick thought there was no danger. Since his death paved the way for Eleanor to surround herself with her own advisers, there was conceivably an element of guilt in her lavish provision for Masses to be said at St Hilaire in Poitiers for the dead constable’s soul. The charter bore both her seal and the autograph crosses of the members of her immediate entourage, whose names recur many times in the coming years: Hugues de Faye, the viscount of Châtellerault, her seneschal Raoul de Faye, her constable Saldebreuil, her steward Hervé and her chaplain and secretary Pierre.

Before Henry could intervene, he had to march again into Brittany, where the latest unrest had been sparked by his own lust. Having taken as hostage Aelis, the daughter of Conan IV, he was now accused by her family of having abused her, for the good reason that she was pregnant and about to give birth to his child. Embroiled in this entanglement, he had to hurry back to Argentan when Louis invaded Normandy yet again.

Count Patrick’s death, accidental or otherwise, suited Eleanor’s plans to regain control of her inheritance. Like her father and grandfather, she travelled widely, receiving homage in Niort and Limoges and as far south as Bayonne, meanwhile dismissing a number of Henry’s administrators, renewing former rights and privileges that he had abolished and restoring many of her vassals whom he had dispossessed.

After a decade and a half of being the perfect feudal wife and queen for Henry and doing in public everything that he demanded – and fifteen years before that during which she had visited Aquitaine as wife of Louis, similarly exercising the ducal powers that marrying her had conferred on him – Eleanor was determined to enjoy the years remaining for herself. Her personal wealth enabled her to dispense great largesse to her relatives and favourite individuals and charities, one of which was the Benedictine abbey of Fontevraud, geographically in Anjou but within the see of Poitiers. Founded by Robert d’Arbrissel on the principle that women – especially elderly widows – were morally better than men, its rule provided for an abbess to rule twin communities of monks and nuns totalling several thousand, divided into the houses of Grand Moustier, La Madeleine for repentant prostitutes, St Lazare for lepers and St Jean de l’Habit for male religious.

Similar thinking made Eleanor respectable at last. A spin-off of Hippocrates’ theory of the uterus moving about in the body was the current medical–philosophical view that women were fouled by their own menstrual blood. For either sex, attaining what we should call middle age was in itself an achievement when so many died young, but women who lived through the menopause were after-wards considered purified, as though infertility turned them into quasi-men, just as the clerical gown excused men from proving themselves as such.

Poitiers was a fitting city for Eleanor’s capital. The palace itself had been extended from its original Merovingian confines by a suite of chambers unlike the comfortless quarters Henry inhabited most of the time. Clustered at one end of the spacious new audience hall – still magnificent as the

salle des pas perdus

or concourse of the law courts – these rooms afforded space and privacy and comfort to Eleanor and her ladies, which makes it a reasonable assumption that they were built to her design in the first place, for Henry would have had no use for them (plates 11, 12).

Not for the countess of Poitou as mistress of her own house the dirt of horses, dogs and hawks, the noise of armourers and blacksmiths, the stink of unwashed sweaty bodies, the ribaldry of soldiers and whores, the discomfort of unglazed windows and public halls heated, if at all, by smoking central fireplaces. This, by the standards of the age, was comfort and elegance such as she had not known since her sojourn in Byzantium and Antioch, whose oriental architecture was echoed in the neighbouring church of Notre-Dame-la-Grande, its ornate triple façade crowded with statues illustrating biblical or moral stories for the illiterate believer.

The city walls had been rebuilt and extended after being partly demolished to make way for the palace extensions. Formerly outlying parishes were now within the walls, providing space for new churches and collegials but also the shops and craftsmen’s workshops and market space that constituted the secure facilities necessary for the development of a prosperous merchant class. The cathedral under construction was fittingly enriched for the seat of a palatine count, with a huge window above the altar depicting Henry and Eleanor in suitably pious poses.

At Montmirail in January 1169, she gained a significant victory when Henry acceded to her pressure to give Aquitaine back to Richard. Eleanor’s favourite now swore loyalty for the duchy to Louis, while Young Henry did homage for Maine and Anjou, after which Louis assented to Prince Geoffrey’s betrothal to Constance, Countess of the Bretons, who was also a hostage in Henry’s keeping. Although the match was consanguineous, Henry had obtained a papal dispensation. By Geoffrey swearing fealty for Brittany to Young Henry, Louis retained suzerainty by subinfeudation.

Henry’s main achievement in this exercise was to persuade Louis to give him another of the ‘superfluity of princesses’. This was nine-year-old Princess Alais, who was now betrothed to Prince Richard.

8

Her dowry was the Berry, which lay between Aquitaine and Burgundy, a piece of land Henry had long wanted to strengthen his eastern frontier. Louis had now given away two princesses in the hope that one would become queen of England and the other duchess of Aquitaine.

Thus, as a respectably sterile dowager duchess-queen Eleanor became the guardian of offspring by both her husbands and many other great families west of the Rhine. Young Henry’s seventeen-year-old wife Marguerite Capet, her younger sister Alais, betrothed to Prince Richard but destined to become yet another of the king’s entrapped mistresses, Constance of Brittany, now betrothed to Prince Geoffrey and Alix of Maurienne, betrothed in infancy to Prince John. All of these young people spent time at the court of Poitiers, which must have seemed to them afterwards like a glorious extended summer day. In addition, Eleanor’s own namesake daughter and the Princess Joanna graced the Poitevin court, as did their brothers Richard and Geoffrey. Even Young Henry came on occasion.