April Queen (42 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

When there was a charter to be signed, she gave it the force of law with her own seal. At Westminster, with William the Marshal at her side, she had the archbishop of Canterbury witness the oath-taking of the greatest magnates of England. For the first time since the Conquest the succession passed without dispute to the eldest surviving son of a dead king. Many of the lords and their ladies present had been infants at the time of Eleanor’s disgrace. Because few people of either sex then lived to her age, people saw in her survival physically and mentally intact the resurrection of a legend. Popular etymology held that her name was a compound of

ali

, the rare and regal sea eagle, and

or

, meaning gold.

It was said that the troubadour Richard the Poitevin had prophesied this upturn in her fortunes: ‘the eagle of the broken covenant shall be gladdened by her third nest[l]ing’.

3

Certainly she was at least as much eagle as Henry had been, and there was no doubt she had broken her covenant with Louis. And certainly it was her third child of the marriage with Henry who had raised her to these new heights, no matter what he had done before. Like most medieval ‘prophecies’, this one was probably the fruit of hindsight, but when it was made is unimportant; that it became legend all over Christendom shows how Eleanor’s longevity, formidable will and change of fortunes made her appear more than a mere mortal to her contemporaries. In case anyone was in any doubt about her new powers, she revived the title she had never renounced, styling herself, ‘by the Grace of God, Queen of the English’.

4

Few were the Anglo-Norman barons who resisted her authority, for it was common knowledge that Henry’s successor – who since his childhood had made only two brief visits to England, at Easter 1176 and Christmas 1184 – had a passion for warfare on a scale that could only be satisfied against non-Christians and would quit England as soon after his coronation as he had amassed enough money for his postponed crusade. Whom could he trust as regent for an absence of two or three years? Not his power-hungry younger brother or Geoffrey the Bastard. Eleanor was the only person with the experience and authority to do the job who would not try to usurp the throne.

Within forty-eight hours of Richard landing at Portsmouth on 13 August, the 31-year-old warrior-king who had not a word of the language spoken by the majority of his island subjects was reunited with her at Winchester. After having the treasury weighed and counted, he gave orders to pay off Henry’s last debt: the 20,000 marks for Philip’s

costs in the recent war, plus 4,000 marks Richard agreed to add to this sum.

5

Amounting to £16,000, this made a considerable dent in the treasury, estimated at a total of £90,000.

6

On 29 August, despite the opposition of the archbishop of Canterbury to the union on the grounds that bride and groom were related in the third degree of consanguinity, John was married. The archbishop placed the estates of both bride and groom under interdict until Pope Clement III granted a dispensation with the curious condition that the couple should have no intercourse. There was in fact no issue to the marriage.

At the same time, to gain the support of the Church, Richard relaxed Henry’s requirement that strings of riding and packhorses should be kept in every monastery to service the transportation needs of his unpredictable progresses. To win over the nobility, who had resented Henry’s policy – copied from his grandfather Henry I – of diluting their ranks with his

novi homines

or new nobles created by elevating through arranged marriages those who served him well, Richard declared all such unions void – which was a second blow for Etienne de Marsai, whose son was one of the new men.

Taking advantage of the interregnum, the Welsh raided several towns across the border. Like a dog with a rabbit, Richard wanted to race off and subdue them, but Eleanor insisted he be crowned first.

7

On 3 September, five days after John’s wedding, the corona-tion at Westminster Abbey assembled the high clergy and nobility of the realm for a ceremony little changed at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II almost eight centuries later. Dressed in the height of fashion in silks and furs, Eleanor was installed in state as befitted a dowager queen, with her court of ladies- and maids-in-waiting, and no one doubted that she was the power behind the throne.

Conducted solemnly into the abbey behind a limping William the Marshal bearing the gold sceptre with its golden cross – a falling gangway had injured him while boarding the ship at Dieppe en route to England – Richard prostrated himself before the altar, was raised to his feet and swore the triple oath, to preserve the Peace of God,

to fight crime, and to show justice and mercy in his judgements. One of the nineteen archbishops and bishops present then asked the assembled clergy, which included thirteen abbots, and the laity, who included John and ten other earls of the realm plus seventeen barons, if they accepted Richard as ruler. Only after their assent could he be anointed.

Gilbert Foliot having recently died, it was the chronicler Ralph of Diceto, in his capacity as dean of London, who handed to Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury the oil with which to anoint Richard on hands, breast, shoulders and arms and then the chrism – a doubly sanctified oil used only by bishops – with which his head was anointed as a token of the awful sacrament of kingship.

Richard was girded with a sword, in imitation of the ceremony of dubbing a knight, and then crowned by the archbishop, assisted by two doyens of the nobility. After seating the crown securely – for to lose it would have been an evil omen indeed – the archbishop invested Richard with the ring, the sceptre and the rod. Only now was he officially king of England.

In a general amnesty Henry’s exiles were recalled and his hostages released; those he had dispossessed were restored.

8

Many of the heiresses he had been keeping – in some cases for years – to bestow on those who served him well were now given to men who would have every reason to praise Richard’s generosity and yet would let him down in his hour of need. Not every woman took her imposed husband without protest. A slightly later example was the widowed Countess Hadwisa, described by one catty chronicler as ‘a woman almost a man, lacking only the virile organs’,

9

who refused point-blank to marry Guillaume de Fors, one of the commanders of Richard’s fleet on the Third Crusade. Only after the Crown had seized her estates in Yorkshire and started selling off everything movable did she give in and marry him.

Anticipating Chapter 39 of Magna Carta, Eleanor released or pardoned in Richard’s name many thousands held in prisons or outlawed under the oppressive forest laws, but never judged by due process of law. As Roger of Howden commented, it was proof how well the dowager queen knew from experience the hatefulness of being locked away.

10

And yet in all the pomp and revelry there was no mention on that coronation day of poor Alais, who should have been installed on the throne occupied by Eleanor, but was still languishing in Winchester, and would be for years to come.

The public celebrations cost a fortune, literally. Item: 900 cups. Item: 1,770 pitchers. Item: 5,050 dishes.

11

Richard’s banquet at Westminster was strictly an affair for men only – and Christian men at that. At the

insistence of Archbishop Baldwin, who argued that their presence would taint the holiness of the sacrament of royalty, the Jews of London were not allowed to mar it by presenting tokens of their respect. Having been introduced into England by the Conqueror, they were under the monarch’s direct protection because they fitted nowhere else in the feudal system. When some did appear with presents for the king, they were forcibly ejected from the festivities, news of which generated a rumour that Richard had ordered them killed and their homes ransacked. The resultant violence and plundering spread like wildfire.

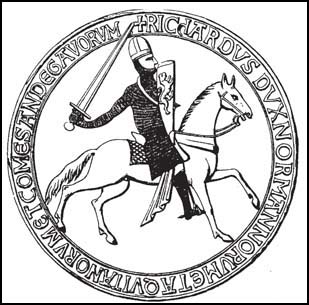

To avoid the riots spreading to Normandy and Poitou and driving abroad the ready source of loans and taxes his Jews represented, messengers were dispatched forbidding any such excesses in his French possessions in the name of ‘Richard, by the grace of God King of the English, Duke of the Normans and Aquitains, Count of the Poitevins’.

12

In London, orders were given to track down the perpetrators, but only three men were caught: one was hanged because he had stolen from a Christian under cover of the riots, and two others because they had set fires which spread to Christian property.

During the three and a half months he spent in England, most of Richard’s energy went into raising money for the crusade. He travelled to Guildford and Arundel in the south, to Salisbury and Marlborough in the west, to Warwick and Geddington in the north and to Bury St Edmunds in East Anglia. While he was there, Henry’s go-between Cardinal Agnani arrived at Dover to mediate a monastic dispute at Canterbury. The reins of power firmly in her hands, Eleanor spat a reminder at the importunate prelate that he required a safe-conduct before entering the realm, and ordered him to return whence he had come.

13

With the proceeds of Henry’s Saladin tithe already given to the Templars, every office of the Crown was put up for auction to raise cash. Many manors passed into the hands of the Church by mortgages that could never be redeemed. Faithful administrators found themselves bidding for their own posts. Eleanor could take pleasure in Glanville being dispossessed of the most important secular office in the country and ruined by fines totalling £15,000 of silver.

14

Yet she did not accede to Richard’s impulse to have him executed for having been her chief jailer. Glanville’s death was not far off in any case. After taking the cross to benefit from the fiscal exemptions available to crusaders, he died outside Acre with Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury before Richard even arrived there.

Two new justiciars were appointed to take over his duties, both elderly. Bishop Hugh of Durham, who had always kept his distance

from Henry and governed much of northern England during his reign, shared office with the old king’s closest adviser William de Mandeville, earl of Essex. In naming them, Richard was showing more respect for their integrity than their capacity for the work of governing the realm during his long absence.

Everything was for sale: fiefs, offices, titles. William the Marshal bought the sheriffdom of Gloucestershire for 50 marks. Even exemptions from taking the cross could be purchased, thanks to an indulgence from Pope Clement III that was intended to allow those vital for the running of the country to remain in England without sin. When Hugh of Durham purchased the earldom of Northumberland, Richard quipped merrily that he had made a new earl out of an old bishop.

15

Even the right to fortify castles could be had for money. The

pax Henrici secundi

had been imposed and sustained by a relentless programme of destroying adulterine castles and ruthless control of the barons; during Richard’s three-month milking of the island realm the work of decades was undone and the tight rein Henry had used to keep the Anglo-Norman barons in check was slackened to start the process that would end with Magna Carta twenty-six years later.

There is no way of estimating how much money was raised in this way because the greater part went directly to Richard; only if the purchaser of an office could not pay was the debt recorded in the Pipe Rolls. Such was the king’s hunger for gold that he offered to sell the entire city of London if he could find a buyer rich enough.

16

The new chancellor, who was also made bishop of Ely, had to pay 3,000 pounds for his seal. William Longchamp was the epitome of the ‘new man’, raised from obscurity to serve his master unquestioningly. Born in Normandy allegedly the grandson of a serf, he had served as Richard’s chancellor in Aquitaine, but knew nothing of England or its language.

However, the measure of their closeness was such that the chancellor’s seal went to him despite the bishop of Bath bidding £1,000 more for it. Given three castles and the Tower of London, Longchamp spent the enormous sum of £1,200 on repairing and extending it in one year. The only gift he made to the recently completed cathedral at Ely, obliged to accept him as bishop, were some relics including teeth said to be from the head of St Peter. In the normal way, the prior of the cathedral looked after the running of the establishment, leaving Longchamp free to travel far and wide on the king’s business.

Meanwhile, Eleanor was making provisions for the style of life she intended leading as regent for however long the crusade might take. She had recovered her dower property and also had Richard attribute to her

the same dower possessions that Henry I and Stephen of Blois had given their wives to cover their outgoings.

17

In addition was the ‘queen geld’ – the supplementary 10 per cent due to her on all fines paid to the king, although this was sometimes commuted at her discretion.