Authors: Wilfred Thesiger

Arabian Sands (7 page)

The deserts in which I had travelled had been blanks in time as well as space. They had no intelligible history, the nomads who inhabited them had no known past. Some bush-men paintings, a few disputed references in Herodotus and Ptolemy, and tribal legends of the recent past were all that had come down to us. But in Syria the patina of human history was thick along the edges of the desert. Damascus and Aleppo

had been old before Rome was founded. Among the towns and villages, invasion after invasion had heaped ruin upon ruin, and each new conquest had imposed new conquerors upon the last. But the desert had always been inviolate. There I lived among tribes who claimed descent from Ishmael, and listened to old men who spoke of events which had occurred a thousand years ago as if they had happened in their own youth. I went there with a belief in my own racial superiority, but in their tents I felt like an uncouth, inarticulate barbarian, an intruder from a shoddy and materialistic world. Yet from them T learnt how welcoming are the Arabs and how generous is their hospitality.

From Syria I went to Egypt and then to the Western Desert, where I was with the Special Air Service Regiment. We travelled in jeeps and were divided into small parties which hid in the desert and attacked the enemy’s lines of communication. We carried food, water, and fuel with us; we required nothing from our surroundings. I was in the desert, but insulated from it by the jeep in which I travelled. It was simply a surface, marked as ‘good’ or ‘bad going’ on the map. Even if we had stumbled on Zarzura, whose discovery had been the ambition of every Libyan explorer I should have felt no interest.

In the last year of the war I was again in Abyssinia, where I was Political Adviser at Dessie in the north. The country required technicians but had little use for political advisers. Frustrated and unhappy I resigned. One evening in Addis Ababa I met O. B. Lean, the Desert Locust Specialist of the Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome. He said he was looking for someone to travel in the Empty Quarter of Arabia to collect information on locust movements. I said at once that I should love to do this but that I was not an entomologist. Lean assured me that this was not nearly as important as knowledge of desert travel. I was offered the job and accepted it before we had finished dinner.

All my past had been but a prelude to the five years that lay ahead of me.

The Wall of Dhaufar collects a

party of Bait Kathir at Salala to

escort me to the sands of Ghanim.

While waiting for their arrival

I travel in the Qarra mountains

.

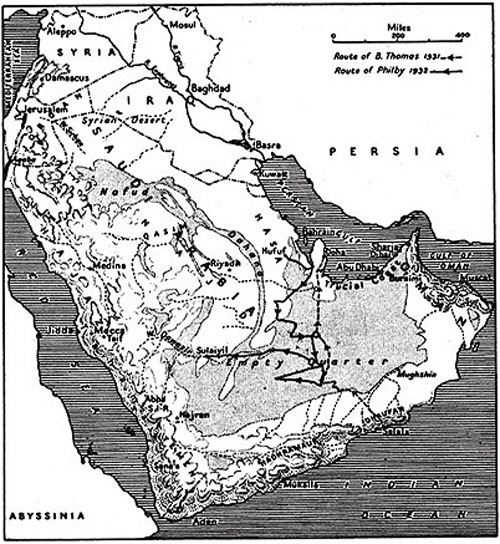

The deserts of Arabia cover more than a million square miles, and the southern desert occupies nearly half of the total area. The southern desert stretches for nine hundred miles from the frontier of the Yemen to the foothills of Oman, and for five hundred miles from the southern coast of Arabia to the Persian Gulf and the borders of the Najd. The greater part of it is a wilderness of sand; it is a desert within a desert, so enormous and so desolate that even Arabs call it the Rub al Khali or the Empty Quarter.

In 1929 T. E. Lawrence wrote to Lord Trenchard, Marshal of the Royal Air Force, suggesting that either the R100 or R101 should be deviated on its trial flight to India to pass over the Empty Quarter. He wrote ‘to go over the empty quarter will be an enormous advertisement for them. It will mark an era of exploration. Nothing but an airship can do it, and I want it to be one of ours which gets the plum.’ Nevertheless in 1930 Bertram Thomas crossed this desert from south to north, and a few months later another Englishman, St John Philby, crossed it again, this time from the north. Thomas and Philby had proved that the Empty Quarter could be crossed with camels, but when I went there fifteen years later they were the only Europeans who had travelled in it, and vast areas between the Yemen and Oman were still unexplored.

When I was at Oxford I had read

Arabia Felix

in which Bertram Thomas described his journey. The month which I had already spent in the Danakil country had given me some appreciation and understanding of desert life, and Lawrence’s

Revolt in the Desert

had awakened my interest in the Arabs; but while at Oxford I longed only to return to Abyssinia. It

was not until later that my thoughts turned more and more insistently to the Empty Quarter. Although I had travelled in the deserts of the Sudan and the Sahara, others had been before me and the mystery was gone: the routes and wells, the dunes and mountains were marked on maps; the tribes were administered. The thrill that I had known when travelling in the Danakil country was missing. The Empty Quarter became for me the Promised Land, but the approaches to it were barred until this chance meeting with Lean gave me my

great opportunity. I was not really interested in locusts. I certainly would not have volunteered to go to Kenya or the Kalahari to look for them, but they provided me with the golden key to Arabia.

Nowadays one of the chief obstacles to travel in the few unexplored places of the world that remain is getting permission from the governments which claim them. It would have been difficult, perhaps even impossible, for me to have approached the Empty Quarter without the initial backing which I received from the Middle East Anti-Locust Unit, but once I had been there and had made friends with the Bedu I could travel where I wished, I had no need to worry about international boundaries that did not even exist on maps.

I had already seen plenty of locusts in the Sudan, and during the year I was at Dessie I had watched swarms rolling across the horizon like clouds of smoke as they arrived on the Abyssinian uplands from their breading places in Arabia. I had watched them going past, long-legged in wavering flight, as thick in the air as snowflakes in a storm. I had seen branches broken from trees by the weight of the settled swarms, and green fields stripped bare in a few hours; but although I knew how destructive they could be, I knew practically nothing about their habits. Therefore, before going to the Empty Quarter, I was sent to Saudi Arabia for two months to learn about locusts from Vesey FitzGerald, who was running a campaign there. Few Europeans had previously been allowed to enter Saudi Arabia, and almost all of them had been confined to Jidda, the port on the Red Sea, where the diplomats and the commercial community lived. Locust officers, however, were allowed to travel freely in nearly all parts of the country.

During the war a species of locust called the ‘desert locust’ had threatened the Middle East with famine. It was known that one of the main breeding grounds was the Arabian peninsula, and in 1943-4 the Middle East Anti-Locust Unit was given permission by King Abd al Aziz ibn Saud to carry out a campaign against them in Saudi Arabia.

Vesey FitzGerald told me of the discoveries which had been made in recent years and which were the reason for my

journey into the Empty Quarter. Dr Uvarov, who was head of the Anti-Locust Research Centre in London, had discovered that both the desert locust and a large solitary grasshopper belonged to the same species, although they differed in their habits, their colours, and even in the structure of their bodies to such an extent that naturalists had named and described them as separate species. These solitary grasshoppers occasionally developed gregarious habits that were probably due to overcrowding. Their numbers would increase after a season of plentiful vegetation, and then in the next dry season when they were confined to a smaller area they would swarm and migrate, ceasing to be solitary grasshoppers and becoming desert locusts. The small initial swarms increased very rapidly, for locusts breed several times a year, and each locust lays as many as a hundred eggs at a time. The eggs hatch in about three weeks and the young locusts or hoppers reach maturity in about six weeks.

In Saudi Arabia with Vesey FitzGerald I saw densely packed bands of hoppers extending over a front of several miles and with a depth of a hundred yards or more, and yet he told me that these were only small bands. I knew that with favourable wind locusts can cover enormous distances, but I was amazed when he told me that swarms can breed in India during the monsoon, move in the autumn to southern Persia or Arabia, breed there again, and then pass on to the Sudan or East Africa. Some of these swarms cover two hundred square miles or more. Eventually disease attacks them and they vanish as quickly as they had appeared. Then for a time there are no more desert locusts in the world, only solitary grasshoppers.

Doctor Uvarov believed that the ‘outbreak centres’ were restricted to certain definite areas and that if these could be located and controlled it would be possible to prevent the solitary grasshoppers from ever swarming. The first thing to do was to locate all these outbreak centres. He thought that some of them might be in southern Arabia, especially at Mughshin,

1

where Thomas had discovered that the great watercourses which ran inland from the coastal mountains of Dhaufar ended against the sands of the Empty Quarter.

Dhaufar was known to get the monsoon, and it seemed probable that enough water flowed inland each year to produce permanent vegetation along the edge of the sands. If this were so, the area would almost certainly be an outbreak centre. I was to go there and find out, but so little was known about this part of southern Arabia that wherever I went I could collect no useful information.

I arrived in Aden at the end of September 1945, visited the mountains along the Yemen frontier, and on IS October flew to Salala, the capital of Dhaufar, which lies about two-thirds of the way along the southern coast of Arabia. It was from there that I was to start my journey. While at Salala I stayed with the R.A.F. in their camp outside the town. It was on a bare stony plain which was shut in by the Qarra mountains a few miles away, and had been set up during the war when an air route from Aden to India was opened. This route was no longer used, but once a week an aeroplane came to Salala from Aden.

Dhaufar belonged to the Sultan of Muscat, and he had insisted, when he allowed the R.A.F. to establish themselves there, that none of them should visit the town or travel anywhere outside the perimeter of the camp unless accompanied by one of his guards, and that none of them should speak to any of the local inhabitants. These restrictions also applied to me while I was staying in the camp. In the case of the R.A.F. they seemed to me to be reasonable, designed to prevent incidents between airmen who knew nothing of Arabs, and tribesmen who were armed, quick-tempered, and suspicious of all strangers; but applied to me, who had come to travel with the people, they were extremely irksome. They meant that I had to make all my arrangements through the Wali, or Governor.

About 1877 Dhaufar had been occupied, after centuries of tribal anarchy, by a force belonging to the Sultan of Muscat, but in 1896 the tribes rebelled, surprised the fort that had been built at Salala, and murdered the garrison. It was several months before the Sultan was able to reassert his authority, which, however, has since remained largely nominal except on the plain surrounding the town.

The morning after my arrival I went into Salala to call on the Wali. Salala is a small town, little more than a village. It lies on the edge of the sea and has no harbour, the rollers from the Indian Ocean sweeping on to the white sands beneath the coconut palms that fringe the shore. When I arrived fishermen were netting sardines, and piles of these fish were drying in the sun. The whole town reeked of their decay. The Sultan’s palace, white and dazzling in the strong sunlight, was the most conspicuous building, and clustered around it was the small

suq

or market, a number of fiat-roofed mud-houses, and a labyrinth of mat shelters, fences, and narrow lanes. The market consisted of only a dozen shops, but it was the best shopping centre between Sur and the Hadhramaut, a distance of eight hundred miles. On my way to the palace I passed the mosque, near which were some old stone buildings and also an extensive graveyard. Scattered on the plain around the town were various ruins, all that remained of a legendary past, for Dhaufar is said to have been the Ophir of the Bible.

The successive civilizations whose prosperity caused the Romans to name all this part of Arabia ‘Arabia Felix’ had been farther to the west. The Minaeans had developed a civilization as early as 1000 B.C. in the north-eastern part of the Yemen. They were traders, with colonies as far north as Maan near the gulf of Aqaba, and they depended for their prosperity on frankincense from Dhaufar which they marketed in Egypt and Syria. They were succeeded by the Sabaeans, who in turn were succeeded by the Himyarites. This southern Arabian civilization, which lasted for 1,500 years, came to an end in the middle of the sixth century A.D., but while it lasted this remote land acquired a reputation for fabulous wealth. For centuries Egypt, Assyria, and the Seleucids schemed and fought to control the desert route along which the frankincense was carried northwards, and in 24

B.C

. the Emperor Augustus sent an army under Aelius Gallus, prefect of Egypt, to conquer the lands where this priceless gum originated. The army marched southwards for nine hundred miles, but lack of water eventually forced it to retire. This was the only time any European power had ever tried to invade Arabia.