Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (18 page)

Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

The 2nd Battalion of the 393rd Infantry had been attached to the 2nd Division, which had just started a new V Corps advance north towards the Roer dams near Schmidt. When they heard heavy firing to the south they thought that the rest of the division was now joining in the same attack. They still had no idea of the German offensive.

An aid man called Jordan, helped by a couple of riflemen, began bandaging the wounded in the comparative shelter of a sunken road.

‘We administered plasma

to a boy whose right arm was attached by shreds,’ a soldier recounted, ‘tried to soothe him and held cigarettes for him to smoke. He was already in shock, his body shaking badly. Shells exploding hundreds of feet away made him flinch. “Get me out of here! For God’s sake get me out of here. That one was close – that one was too damn close. Get me out of here,” he kept saying.’ Jordan, the aid man, received a bullet through the head. ‘We heard later that day that our boys shot a German medic in retaliation, somewhat mitigated by the fact that he was carrying a Luger.’ Not knowing what was going on, and angry at having to give up ground they had just taken in the advance towards the dams, they were ordered to halt and turn round. Orders were to withdraw south-west towards Krinkelt to face the 12th SS Panzer-Division.

While most of the 99th Division fought valiantly in the desperate battles, ‘a few men broke under the strain’, an officer acknowledged, ‘wetting themselves repeatedly, or vomiting, or showing other severe physical symptoms’. And ‘the number of allegedly accidental rifle shots through hands or feet, usually while cleaning the weapon, rose sharply’. Some men were so desperate that they were prepared to maim themselves even more seriously. A harrowing example in the 99th Infantry Division was a soldier who was said to have ‘lain down beside a large tree, reached around it, and exploded a grenade in his hand’.

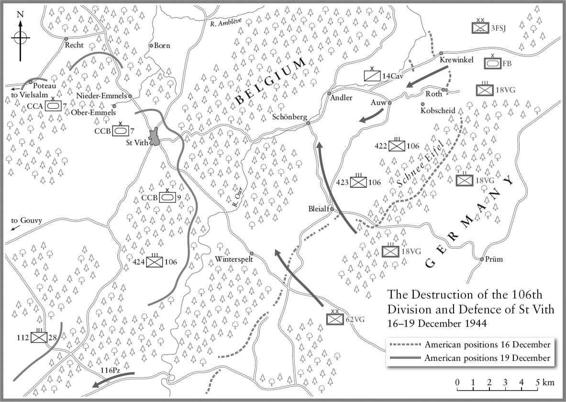

The newly arrived and even less experienced 106th Infantry Division to the south, in the Schnee Eifel, would be shattered by the German offensive over the next three days. It was rapidly outflanked when the 14th Cavalry Group in the Losheim Gap, covering the area between the 99th Division and the 106th, retreated without warning. This also left the right flank of the 99th vulnerable. As its 395th Infantry Regiment pulled back in desperate haste, soldiers bitterly remembered the slogan

‘The American Army never retreats!’

Having received no rations, they forced open some drums of dried oatmeal. So desperate were they that they tried to stuff handfuls of it into their mouths and fill their pockets. An officer recorded that one soldier even offered another $75 for a thirteen-cent can of Campbell’s soup.

The cavalry group had faced an almost impossible task. Strung out in isolated positions across a front of nearly nine kilometres, its platoons could only attempt to defend fixed positions in villages and hamlets. There was no continuous line and the cavalry was not manned, trained nor equipped for a stationary defence. All it had were machine guns dismounted from reconnaissance vehicles, a few anti-tank guns and a battalion of 105mm howitzers in support. The very recent arrival of the 106th meant that no co-ordinated plan of defence had been established.

In the days before the offensive, German patrols had discovered that there was a gap nearly two kilometres wide between the villages of Roth and Weckerath in the 14th Cavalry sector. So, before dawn, the bulk of the 18th Volksgrenadier-Division, supported by a brigade of assault guns, advanced straight for this hole in the American line, which lay just within the northern boundary of the Fifth Panzer Army. Manteuffel’s initial objective was the town of St Vith, fifteen kilometres to the rear of the American front line on the road from Roth.

In the murky grey daylight, the men of the 14th Cavalry at Roth and Weckerath found that the Germans were already behind them, having slipped through partly concealed by the low cloud and drizzle. Communications collapsed as shell bursts cut field telephone cables and German intercept groups played records at full volume on the wavelengths which the Americans used. The surrounded cavalry troopers in Roth fought on for much of the day, but surrendered in the afternoon.

The 106th Division did not collapse immediately. With more than thirty kilometres of front to defend, including a broad salient just forward

of the Siegfried Westwall, it faced major disadvantages, especially when its left flank was burst open on the 14th Cavalry sector around Roth. With eight battalions of corps artillery in support, it inflicted heavy casualties on the volksgrenadiers, used as cannon fodder to break open the front for the panzer divisions. But the 106th Division did little to counter-attack the flank of the German breakthrough on its left, and this would lead to disaster the next day.

As Model’s artillery chief observed, the difficult terrain of wooded country slowed the advance of the German infantry and made it very hard for his artillery to identify its targets. Also Volksgrenadier divisions did not know how to make proper use of artillery support. They were not helped by the strict orders on radio silence, which had prevented signals nets from being established until the opening bombardment.

Communications were even worse on the American side. Middleton’s VIII Corps headquarters in Bastogne had no clear idea of the scope of the offensive. And at First Army in Spa, General Hodges assumed that the Germans were mounting

‘just a local diversion’

to take the pressure off the V Corps advance towards the Roer river dams. And yet although V-1 ‘buzz-bombs’, as the Americans called them, were now passing overhead every few minutes to bombard Liège, Hodges still did not recognize the signs.

*

Despite General Gerow’s urging, he refused to halt the 2nd Division’s advance north. In Luxembourg at 12th Army Group headquarters during the 09.15 briefing, the G-3 officer reported no change on the Ardennes sector. By then General Bradley was on his way to Versailles to discuss manpower shortages with General Eisenhower.

A diary kept by Lieutenant Matt Konop with the 2nd Division’s headquarters gives an idea of how Americans, even those close to the front, could take so long to comprehend the scale and scope of the German offensive. Konop’s entry for 16 December began:

‘05.15: Asleep in

Little Red House with six other officers – hear loud explosions – must be a dream – still think it’s a dream – must be our own artillery – can’t be, that stuff seems to be coming in louder.’ Konop got up in the dark

and padded to the door in his long johns. He opened it. An explosion outside sent him scurrying back to wake everyone else. They all rushed down into the cellar in their underclothes, finding their way with flashlights. Eventually, when the shelling eased, they returned upstairs. Konop called the operations section to ask if there was anything unusual to report. ‘No, nothing unusual,’ came the answer, ‘but [we] had quite a shelling over here. Nothing unusual reported from the lines.’ Konop crawled back to his mattress, but could not get back to sleep.

It was still dark at 07.15 when he reached the command post at Wirtzfeld. The progress of the 2nd Division’s advance appeared satisfactory on the situation map. Its 9th Infantry Regiment had just captured the village of Wahlerscheid. An hour later Konop looked round Wirtzfeld. There were no casualties from the shelling, except that a direct hit on a heap of manure resulted ‘in the pile being suddenly transported over the entire kitchen, mess-hall and officers’ mess of the Engineer Battalion’. Later in the morning, he agreed with the division’s Catholic chaplain that after the morning’s bombardment they should be careful about holding mass in the church next day because it was an obvious target.

At 17.30 hours, Konop saw a report that German tanks had broken through the 106th Division. This was described as a

‘local enemy action’

. Having nothing else to do, he returned to his room to read. He then spent the evening chatting with a couple of war correspondents who had arrived to doss down. Before going to ‘hit the hay’, he showed the two journalists the door to the cellar in case there was another bombardment the next morning.

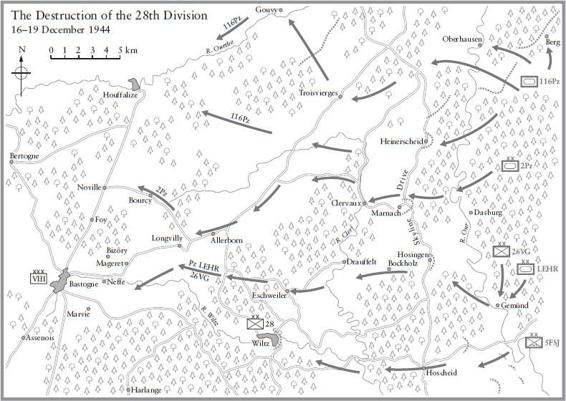

Cota’s 28th Division, adjoining the 106th to the south-west, was initially taken by surprise because of the bad visibility, but the Germans’ use of artificial moonlight proved a ‘blunder’.

‘They turned searchlights

into the woods and then on clouds above our positions, silhouetting their [own] assault troops. They made easy targets for our machinegunners.’

Fortunately, before the offensive began the division had trained infantry officers and NCOs to act as forward observers for the artillery. One company of the division’s 109th Infantry Regiment, which was dug in, brought down 155mm howitzer fire just fifty metres in front of its

own position during a mass attack. It claimed a body count of 150 Germans afterwards for no American casualties.

The compulsion to exaggerate achievements and the size of enemy forces was widespread.

‘Ten Germans will be reported as a company,’

a battalion commander in the division complained, ‘two Mark IV tanks as a mass attack by Mark VIs. It is almost impossible for commanders to make correct decisions quickly unless reports received are what the reporter saw or heard and not what he imagined.’

The 112th Infantry Regiment of Cota’s 28th Division found that

‘on the morning

of the initial assault, there were strong indications that the German infantry had imbibed rather freely of alcoholic beverage … They were laughing and shouting and telling our troops not to open fire, as it disclosed our positions. We obliged until the head of the column was 25 yards to our front. Heavy casualties were inflicted. Examination of the canteens on several of the bodies gave every indication that the canteen had only a short time before contained cognac.’

Waldenburg’s 116th Panzer-Division attacked on the boundary between the 106th and 28th Divisions. But, instead of finding a gap, the Germans were taken in the flank by the extreme right-hand battalion of the 106th and a platoon of tank destroyers. In the forest west of Berg, Waldenburg reported, the assault company of his 60th Panzergrenadier-Regiment was not merely stopped but

‘nearly destroyed’

when the Americans ‘fought very bravely and fiercely’. The Germans rushed forward artillery to cover the river crossings, but the woods and hills made observation very difficult and the steep slopes offered few places to site their batteries.

Waldenburg’s 156th Panzergrenadier-Regiment to the south, on the other hand, advanced rapidly to Oberhausen. Then he found that the dragons’ teeth of the Siegfried Line defences made it impossible for the panzer regiment to follow its prescribed route. He had to obtain permission from his corps headquarters to allow it to follow the success of the 156th Panzergrenadiers who had seized crossing points over the River Our. The heavy rains and snow in the Ardennes had made the ground so soft that panzer units were restricted to surfaced roads. Tank tracks churned the mud of lesser routes to a depth of one metre, making them impassable for wheeled vehicles, and even other panzers. The bad weather which Hitler had wanted to shield his forces from Allied airpower came at a high price, and so did the wild, forested terrain, with which he had concealed his purpose.

Further south, the 26th Volksgrenadier-Division had the task of opening the front for Manteuffel’s most experienced formations, the 2nd Panzer-Division and the Panzer Lehr Division. They hoped to reach Bastogne, which lay less than thirty kilometres to the west as the crow flies, during that night or early the next morning. But Generalmajor Heinz Kokott, the commander of the 26th Volksgrenadiers, had an unpleasant surprise. The 28th Division fought on even after its line along the high ground and road known as ‘Skyline Drive’ had been broken. What had not been expected, he wrote later,

‘was the fact that

the remnants of the beaten units did not give up the battle. They stayed put and continued to block the road.’ This forced the German command to accept that ‘the infantry would actually have to fight its way forward’, and not just open a way for the panzer divisions to rush through to the Meuse. ‘At the end of the first day of the offensive, none of the objectives set by the [Fifth Panzer] Army were reached.’ The ‘stubborn defense of Hosingen’ lasted until late in the morning of the second day.